窶廝urned Potato窶・by Tadayoshi Irino

|

Ken's favorite food was whole potatoes, boiled. On the morning of the atomic bombing, he had pestered his mother for another potato from the pot. The blast from the atomic bomb blew Ken right from the house, and he fled up the side of a mountain. Looking down on his neighborhood, now in flames, he saw the pot with the potato inside, burned and blackened. |

A child's mind hurt by the atomic bomb

Small things are very important

|

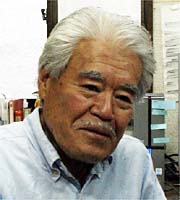

Tadayoshi Irino

Born in 1939 in Higashi Ward, Hiroshima, where he now resides. He graduated from Musashino Art University. In 1975, his oil painting work received a prize at the Modern Japanese Art Exhibition sponsored by the Mainichi Shimbun. He traveled to China in 2002 as part of the Japanese Government Oversea Programme for Artists. His work includes a mural painted on the outer wall of the Hiroshima Detention Center.

The painter Tadayoshi Irino, 71, created this picture book based on his own experience of the bombing. "It's only about one potato. But I want readers to understand that even a small thing like this is very important," he said, emphasizing his words.

The impetus to produce this picture book came more than 20 years ago. Chobunsha, a publisher in Tokyo that had already published books about the atomic bombings, such as the comic book series "Barefoot Gen," appealed to painters in Hiroshima to create A-bomb-related picture books. Seven painters became involved, and seven books were published. Among them was "Burned Potato," published in 1989.

It was Mr. Irino's first experience creating a book for children. His intention, though, was to craft a book that both children and adults could appreciate. He used colored pencils, ink, oil paint, and other materials, and employed various techniques to produce the pictures for the book. "I didn't simply want to make pictures that followed a text," he said, explaining his aim. "Rather, I wanted to tell the story with the pictures, even if no text appeared."

Mr. Irino was 5 years old at the time of the atomic bombing. He was at home, located about 20 meters southwest of his house and studio today, when the bomb was dropped. He was eating breakfast, and had just eaten one potato and was begging his mother for another potato from the pot.

The blast blew him from the house and he fled up a mountain opposite the hypocenter. He gazed down at the burning city and felt with regret, "If I had known such a thing would happen, I would have eaten that potato." For some time after the war, whenever he saw a potato, it brought back painful memories of his ruined house, the city destroyed and in flames, and the awful smells in the air.

When he reached his 30s, he began to eat only one whole boiled potato every August 6. "There's an abundance of things to eat in society today," he explained. "But one day each year I want to go back to that time and remember what it was like on August 6."

For Mr. Irino, the link between potatoes and the atomic bomb can't be undone. "It seems like a tiny thing, but in my case, the atomic bombing deprived me of that potato," he recalled. "A small child's mind can be hurt deeply by such things." The experience has led to his opposition to nuclear weapons and nuclear energy, and his orientation toward peace. As for today's junior high and high school students, Mr. Irino hopes they will adopt a way of looking at the world in which importance is attached even to the smallest things.

These days he is drawing Hiroshima's A-bombed trees in ink and producing postcards of these drawings. He began this effort four or five years ago and has drawn 30 trees to date. "After the bombing, it was said that no plants would grow in the city for 70 years, but A-bombed trees budded the very next year. I want their existence to be honored more," he explained. He plans to create postcards of 150 A-bombed trees.

| This is the final article in the series "Handing down August 6." |

|