Early autopsy reports on 19 A-bomb victims are kept at Hiroshima University

Aug. 5, 2017

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

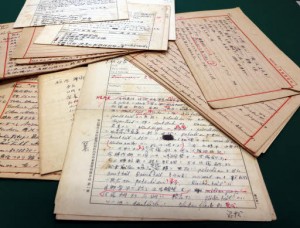

It has been learned that early autopsy reports on 19 A-bomb victims have been kept in the Department of Molecular Pathology at the Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences at Hiroshima University. These autopsies were conducted by Dr. Chuta Tamagawa, then a professor at Hiroshima Prefectural Medical School (now Hiroshima University School of Medicine), in a makeshift hut near the Hiroshima Teishin Hospital from August 29 to October 13, 1945. The autopsy reports are particularly valuable in terms of examining the impact of radiation on the body at an early stage.

Dr. Tamagawa (1897-1970) was transferred from Okayama Medical College (now Okayama University), where he worked as an associate professor, to Hiroshima Prefectural Medical School in the spring of 1945. He became one of the school’s first professors after its accreditation. Prior to the atomic bombing on August 6, the school had evacuated its work to what is now the city of Akitakata. Dr. Tamagawa went into Hiroshima on August 8 and asked Hiroshima Prefecture for permission to do autopsies on A-bomb victims, but this request was declined.

Hearing reports of symptoms like hair loss and bruising, conditions that could not be explained, Dr. Tamagawa felt that there was no time to lose. He headed back to Hiroshima on August 27 and appealed for the cooperation of Dr. Michihiko Hachiya, a former colleague at Okayama Medical College who had become the director of Hiroshima Teishin Hospital. Dr. Hachiya had posted warnings about “A-bomb disease” in his hospital and also felt that autopsies were needed. Using boards from wood that had been turned into huts by the Akatsuki Corps, Dr. Tamagawa fashioned a table for autopsies.

The first autopsy was performed on a 26-year-old woman who was at Teppo-cho, 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing. She died on August 27. The second autopsy was on August 30 and involved a 58-year-old man. With the help of demobilized doctors and medical students from Okayama Medical College, who wrote down the results, a total of 19 autopsies were performed by October 13.

The autopsy reports were carefully made, including pathological findings for the bodies of each victim and symptoms of acute radiation sickness.

To clarify the impact of their exposure to the A-bomb’s radiation, pathological processes in the bodies of the victims were also studied by a survey team dispatched by the Imperial General Headquarters and by Dr. Kiyoshi Yamashina’s investigative committee from the Army Ministry. Dr. Yamashina’s team came to Hiroshima on August 8 and began performing autopsies on August 10 at the quarantine facility on Ninoshima Island, located off the coast of Hiroshima. A team from Kyoto Imperial University also began its examination in Hiroshima.

The “Tamagawa Report” relates the difficulties faced by the medical professionals of the A-bombed city who sought to prepare early reports on the unprecedented disaster. When the U.S.-led Armed Forces Joint Commission for Investigating the Effects of the Atomic Bomb in Japan came to Hiroshima in October, they confiscated the specimens Dr. Tamagawa had collected. But there remained a list in which Dr. Tamagawa wrote down what the team confiscated from him.

Dr. Tamagawa revealed his autopsy reports on the 19 A-bomb victims who died of A-bomb diseases in Hiroshima in Investigative Reports of A-bomb Damage published by the Science Council of Japan in 1953, one year after the occupation of Japan by the Allied Forces ended. During his career as a professor at Hiroshima University School of Medicine, he discovered that the epidermis of keloid scars from A-bomb burns could turn cancerous. The pathological specimens that had been confiscated were returned by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in 1973. These materials were then kept by the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine at Hiroshima University.

Akiko Kubota, an assistant professor at the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, checked the materials along with the notes left behind by those involved, and confirmed that Dr. Tamagawa’s reports were written soon after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Dr. Wataru Yasui, the dean of the Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences at Hiroshima University, said, “The autopsy records created by Dr. Tamagawa are valuable materials that help us understand how the A-bomb victims died. His sense of mission, as a pathologist, drove him to carry out those autopsies in order to investigate the unknown pathological conditions amid such devastating circumstances. I would like people to know, while respecting the privacy of the victims, that these historic autopsy reports exist and are being kept at Hiroshima University.”

(Originally published on August 5, 2017)

It has been learned that early autopsy reports on 19 A-bomb victims have been kept in the Department of Molecular Pathology at the Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences at Hiroshima University. These autopsies were conducted by Dr. Chuta Tamagawa, then a professor at Hiroshima Prefectural Medical School (now Hiroshima University School of Medicine), in a makeshift hut near the Hiroshima Teishin Hospital from August 29 to October 13, 1945. The autopsy reports are particularly valuable in terms of examining the impact of radiation on the body at an early stage.

Dr. Tamagawa (1897-1970) was transferred from Okayama Medical College (now Okayama University), where he worked as an associate professor, to Hiroshima Prefectural Medical School in the spring of 1945. He became one of the school’s first professors after its accreditation. Prior to the atomic bombing on August 6, the school had evacuated its work to what is now the city of Akitakata. Dr. Tamagawa went into Hiroshima on August 8 and asked Hiroshima Prefecture for permission to do autopsies on A-bomb victims, but this request was declined.

Hearing reports of symptoms like hair loss and bruising, conditions that could not be explained, Dr. Tamagawa felt that there was no time to lose. He headed back to Hiroshima on August 27 and appealed for the cooperation of Dr. Michihiko Hachiya, a former colleague at Okayama Medical College who had become the director of Hiroshima Teishin Hospital. Dr. Hachiya had posted warnings about “A-bomb disease” in his hospital and also felt that autopsies were needed. Using boards from wood that had been turned into huts by the Akatsuki Corps, Dr. Tamagawa fashioned a table for autopsies.

The first autopsy was performed on a 26-year-old woman who was at Teppo-cho, 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing. She died on August 27. The second autopsy was on August 30 and involved a 58-year-old man. With the help of demobilized doctors and medical students from Okayama Medical College, who wrote down the results, a total of 19 autopsies were performed by October 13.

The autopsy reports were carefully made, including pathological findings for the bodies of each victim and symptoms of acute radiation sickness.

To clarify the impact of their exposure to the A-bomb’s radiation, pathological processes in the bodies of the victims were also studied by a survey team dispatched by the Imperial General Headquarters and by Dr. Kiyoshi Yamashina’s investigative committee from the Army Ministry. Dr. Yamashina’s team came to Hiroshima on August 8 and began performing autopsies on August 10 at the quarantine facility on Ninoshima Island, located off the coast of Hiroshima. A team from Kyoto Imperial University also began its examination in Hiroshima.

The “Tamagawa Report” relates the difficulties faced by the medical professionals of the A-bombed city who sought to prepare early reports on the unprecedented disaster. When the U.S.-led Armed Forces Joint Commission for Investigating the Effects of the Atomic Bomb in Japan came to Hiroshima in October, they confiscated the specimens Dr. Tamagawa had collected. But there remained a list in which Dr. Tamagawa wrote down what the team confiscated from him.

Dr. Tamagawa revealed his autopsy reports on the 19 A-bomb victims who died of A-bomb diseases in Hiroshima in Investigative Reports of A-bomb Damage published by the Science Council of Japan in 1953, one year after the occupation of Japan by the Allied Forces ended. During his career as a professor at Hiroshima University School of Medicine, he discovered that the epidermis of keloid scars from A-bomb burns could turn cancerous. The pathological specimens that had been confiscated were returned by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in 1973. These materials were then kept by the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine at Hiroshima University.

Akiko Kubota, an assistant professor at the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, checked the materials along with the notes left behind by those involved, and confirmed that Dr. Tamagawa’s reports were written soon after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Dr. Wataru Yasui, the dean of the Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences at Hiroshima University, said, “The autopsy records created by Dr. Tamagawa are valuable materials that help us understand how the A-bomb victims died. His sense of mission, as a pathologist, drove him to carry out those autopsies in order to investigate the unknown pathological conditions amid such devastating circumstances. I would like people to know, while respecting the privacy of the victims, that these historic autopsy reports exist and are being kept at Hiroshima University.”

(Originally published on August 5, 2017)