Messages from A-bomb Survivors: Yoshito Matsushige, Part 1

Dec. 7, 2010

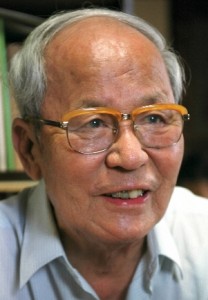

Yoshito Matsushige, 88, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Viewfinder fogged up with tears

Note: This series first appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in 2001.

When I looked through the viewfinder, I saw the wounded staring back at me. It distressed me even more to take photos of them. But it was the worst catastrophe that Hiroshima had ever suffered, and what if I hadn’t taken any photos of the devastation that day? I felt strongly that that would have been a foolish mistake.

Sense of mission was on my mind

As someone working in the media, I didn’t want people asking afterward, “Didn’t you take any photos?” I felt a sense of mission, as the only one around who could take pictures at the time. Still, it took 20 or 30 minutes for me to muster the nerve to do it.

Back then, Mr. Matsushige was a staff photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun. About two hours after the bombing, at about 10:30 a.m., he took two photos of the victims that had clustered around the police station near the west end of the Miyuki Bridge, which spans the Kyobashi River.

When I was set to take the second photo at the Miyuki Bridge, I found that the viewfinder was fogged up with my own tears. It wasn’t anger, but tears came to my eyes when I thought of how the United States had done such a terrible thing and I felt sorry for the people who were wounded and in such misery.

I wanted to take some photos from the side of the police station. I watched people treating the wounded, their faces, too. It was such a horrible scene that I couldn’t look through the viewfinder. I went closer to them, but I just couldn’t take any pictures. I felt so awkward that I muttered to no one in particular, “This is terrible, isn’t it?”

Later that day, Mr. Matsushige took a photo inside his house in Midorimachi, which included the family barbershop, and another photo outside. He also photographed a police officer writing out certificates for the victims to receive relief supplies. In all, he took five priceless images on the day of the bombing.

It was good that I took those photos. Of course, the images don’t convey the whole picture of the catastrophe of the atomic bombing, but if I hadn’t done it, there would be no record of what happened. Even many others in the media didn’t take any photos that day.

There were also professional photographers in the city, but none of them were able to take pictures, either. My photos are the only ones that were taken in the city on the day of the bombing. As a member of the press, I lived up to my responsibility. I fulfilled my mission, I think.

Mr. Matsushige lives with his wife. He now suffers from kidney trouble, and visits the hospital twice a week to receive dialysis.

I led a fortunate life

I think I can now reveal the fact that I received a draft notice around July 1945. But two lieutenants at the military headquarters decided to revoke it. They thought it was better to use me as a member of the press corps at the headquarters than as a private.

I was lucky on the day of the bombing, too. The night before, I was at the Chugoku District Military Headquarters (on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle). On the morning of August 6, I thought it would be too early to go directly to work, so I went home to Midorimachi to have breakfast. Come to think of it, that was the dividing line between life and death.

I left home after breakfast, before eight o’clock, and rode my bicycle to the near side of the Miyuki Bridge, but I turned for home again to use the bathroom. If I hadn’t gone home, if I’d gone to work at that time, I would have suffered the bombing near city hall.

When I look back, I really feel that luck was with me. I was saved three times, that’s why I was able to take those photos that day.

(Originally published on August 10, 2001)

Viewfinder fogged up with tears

Note: This series first appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in 2001.

When I looked through the viewfinder, I saw the wounded staring back at me. It distressed me even more to take photos of them. But it was the worst catastrophe that Hiroshima had ever suffered, and what if I hadn’t taken any photos of the devastation that day? I felt strongly that that would have been a foolish mistake.

Sense of mission was on my mind

As someone working in the media, I didn’t want people asking afterward, “Didn’t you take any photos?” I felt a sense of mission, as the only one around who could take pictures at the time. Still, it took 20 or 30 minutes for me to muster the nerve to do it.

Back then, Mr. Matsushige was a staff photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun. About two hours after the bombing, at about 10:30 a.m., he took two photos of the victims that had clustered around the police station near the west end of the Miyuki Bridge, which spans the Kyobashi River.

When I was set to take the second photo at the Miyuki Bridge, I found that the viewfinder was fogged up with my own tears. It wasn’t anger, but tears came to my eyes when I thought of how the United States had done such a terrible thing and I felt sorry for the people who were wounded and in such misery.

I wanted to take some photos from the side of the police station. I watched people treating the wounded, their faces, too. It was such a horrible scene that I couldn’t look through the viewfinder. I went closer to them, but I just couldn’t take any pictures. I felt so awkward that I muttered to no one in particular, “This is terrible, isn’t it?”

Later that day, Mr. Matsushige took a photo inside his house in Midorimachi, which included the family barbershop, and another photo outside. He also photographed a police officer writing out certificates for the victims to receive relief supplies. In all, he took five priceless images on the day of the bombing.

It was good that I took those photos. Of course, the images don’t convey the whole picture of the catastrophe of the atomic bombing, but if I hadn’t done it, there would be no record of what happened. Even many others in the media didn’t take any photos that day.

There were also professional photographers in the city, but none of them were able to take pictures, either. My photos are the only ones that were taken in the city on the day of the bombing. As a member of the press, I lived up to my responsibility. I fulfilled my mission, I think.

Mr. Matsushige lives with his wife. He now suffers from kidney trouble, and visits the hospital twice a week to receive dialysis.

I led a fortunate life

I think I can now reveal the fact that I received a draft notice around July 1945. But two lieutenants at the military headquarters decided to revoke it. They thought it was better to use me as a member of the press corps at the headquarters than as a private.

I was lucky on the day of the bombing, too. The night before, I was at the Chugoku District Military Headquarters (on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle). On the morning of August 6, I thought it would be too early to go directly to work, so I went home to Midorimachi to have breakfast. Come to think of it, that was the dividing line between life and death.

I left home after breakfast, before eight o’clock, and rode my bicycle to the near side of the Miyuki Bridge, but I turned for home again to use the bathroom. If I hadn’t gone home, if I’d gone to work at that time, I would have suffered the bombing near city hall.

When I look back, I really feel that luck was with me. I was saved three times, that’s why I was able to take those photos that day.

(Originally published on August 10, 2001)