Mitsuo Kodama, 81, Minami Ward, Hiroshima

Jul. 3, 2014

Lost many friends near hypocenter

Affected by chromosomal abnormalities: Telling of A-bomb experiences

by Daisuke Yamamoto, Staff Writer

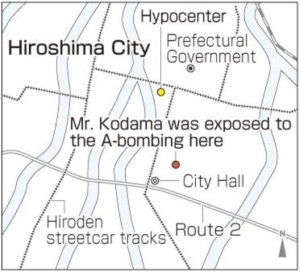

Mitsuo Kodama, 81, was a mere 870 meters from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing. Then 12 years old, Mr. Kodama was exposed to a large amount of radiation, and his cells were damaged. He has undergone 19 operations for cancer, and there is no hope of repairing his chromosomal abnormalities. Mr. Kodama continues to emphasize the horror of nuclear weapons saying, “No one else must ever experience what I did.”

At the time of the A-bombing, Mr. Kodama was a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School). He was in a classroom in the one-story wooden school building, which was located in Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward). “A yellow pillar of flames came down in the courtyard, and I passed out. When I came to, the school building had been completely flattened.” Sandwiched in the space between his desk and chair, Mr. Kodama, who was small, was miraculously unharmed.

It was pitch black outside, and the sun was obscured by haze. After Mr. Kodama had pulled several of his classmates out from under the collapsed school building, it began to be engulfed in flames. Many students who were trapped and could not move started calling for help from their mothers. Before long the students began softly singing the school song. Mr. Kodama put his hands together prayerfully, cried out “Forgive me, friends!” through tears and left. Of the about 300 of his classmates who had come to school that day, only 19 survived.

After traveling on foot and by train, late that night Mr. Kodama finally reached the house in Hesaka (now part of Higashi Ward) to which his family had relocated for safety. But one week later his hair and eyebrows began to fall out. He bled from his gums and the corners of his eyes and had a high fever of 42 degrees C. Purple spots appeared on his body. The doctor who came to the house to care for him didn’t think he would live, but in September his fever broke and his condition stabilized. “My mother brewed tea from dokudami [a medicinal plant] for me and rubbed roasted dokudami on the wounds that had festered. She put her heart and soul into nursing me. It was her love that kept me alive,” he said.

For years afterwards Mr. Kodama had no major illnesses, but in his 60s, one after another cancers were discovered, including cancer of the skin, rectum, stomach and thyroid gland. It was not a case of metastasis. Rather, multiple forms of cancer occurred simultaneously in different organs. Mr. Kodama had 19 operations, including 16 for skin cancer.

In September 2007, a test conducted at the Radiation Effects Research Foundation found that Mr. Kodama’s cells had chromosomal abnormalities as a result of the A-bombing. He was experiencing frequent chromosomal “translocations” in which a whole chromosome or a segment of a chromosome becomes attached to or interchanged with another chromosome or segment. In Mr. Kodama’s case this was occurring at an average of one translocation per cell, disrupting his genetic material and leading to cancer. He was told that this condition would not go away.

The test results indicated that Mr. Kodama had been exposed to about 4.6 gray of radiation, in excess of 4.0 gray, the amount regarded as a fifty percent lethal dose. This represents the amount at which half of those exposed would die within two months.

For many years Mr. Kodama never spoke about his A-bomb experiences. But he came to believe that, having survived, he had a duty to tell as many people as possible that nuclear weapons were inhumane. So he began telling his story. Now he shares his experiences and feelings with others who will continue to convey them as part of a program established by the City of Hiroshima to pass on survivors’ memories.

When telling of his experiences, he makes use of medical materials such as pictures of chromosomes. “I show objective data that illustrates that radiation harms people’s internal organs, and I try to explain things in a simple, persuasive manner,” he said.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Consider how to eliminate discrimination

I learned that many survivors were accused of being able to pass the harmful effects of radiation from the atomic bomb on to others, and it was difficult for many of them to get married or find a job once it became known that they were A-bomb survivors. I would have found that kind of treatment completely unacceptable. There was similar discrimination after the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima. I felt it was our mission to consider how to eliminate it. (Yoshiko Hirata, first-year junior high school student)

Expand circle of peace through conversation

Mr. Kodama talked about how the school building was instantly flattened by the atomic bomb and how the swimming pool at the school was full of students who had been burned. I could picture the terrible scene. He asked me to tell my family and friends about what I’d heard from him. When I told my mother, she listened carefully. I think that by listening and then thinking about what we have heard, the circle of peace will expand. (Kohei Hayashi, first-year high school student)

Learning about horror of continued impact

It was my first time to see a photo of the chromosomes of an atomic bomb survivor. There should be two identical chromosomes side by side, but in Mr. Kodama’s case, their lengths and shapes were different. I was really surprised. He said it’s a miracle that he is alive. He is still affected by the atomic bomb almost 70 years later. We must continue to emphasize that nuclear weapons must never be used again. (Ryo Kamiyasu, third-year high school student)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Mitsuo Kodama came to Kokutaiji High School to have his picture taken by the monument to the students of First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School. He pointed to each name and said things like this: “He was full of energy. I couldn’t save him.” “He wanted to be a doctor, so he went to medical school, but he had to give up his studies because he developed cataracts on account of the A-bombing.” His sorrow, regret and distress come across, and it was heart-wrenching. He sometimes seemed to be looking off into the distance, and I supposed he was alternately recalling good times with his classmates and the A-bombing.

When Mr. Kodama talks about the hardships he has suffered, including chromosomal abnormalities and multiple kinds of cancer, every word has an impact. But it’s not because he is wondering why all these things had to happen to him. Rather, it is his strong determination that we must all work together to eliminate inhumane weapons. Listening to him, I sensed the importance of what he had to say.

He told his story carefully, sometimes asking the junior high school-age junior writers, “Are you following me?” “If you look at the other person’s expression, it’s easy to tell whether or not you’re getting through,” he said. “It’s difficult to really get your message across.” What with the seriousness and powerful impact of Mr. Kodama’s story, after the interview I couldn’t do anything else for the rest of the day. But I was glad I to have been able to hear his story directly from him, and I felt I really wanted to tell my family and friends about it. That’s what Mr. Kodama is hoping for when he talks about passing on memories, and being able to make others feel that way is the result of Mr. Kodama’s expert ability to tell his story. (Daisuke Yamamoto)

◆Articles in the “Passing On Memories” are published occasionally and can be found in the “Survivors’ Stories” section of this website.

(Originally published on May 26, 2014)

Affected by chromosomal abnormalities: Telling of A-bomb experiences

by Daisuke Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Mitsuo Kodama, 81, was a mere 870 meters from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing. Then 12 years old, Mr. Kodama was exposed to a large amount of radiation, and his cells were damaged. He has undergone 19 operations for cancer, and there is no hope of repairing his chromosomal abnormalities. Mr. Kodama continues to emphasize the horror of nuclear weapons saying, “No one else must ever experience what I did.”

At the time of the A-bombing, Mr. Kodama was a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School). He was in a classroom in the one-story wooden school building, which was located in Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward). “A yellow pillar of flames came down in the courtyard, and I passed out. When I came to, the school building had been completely flattened.” Sandwiched in the space between his desk and chair, Mr. Kodama, who was small, was miraculously unharmed.

It was pitch black outside, and the sun was obscured by haze. After Mr. Kodama had pulled several of his classmates out from under the collapsed school building, it began to be engulfed in flames. Many students who were trapped and could not move started calling for help from their mothers. Before long the students began softly singing the school song. Mr. Kodama put his hands together prayerfully, cried out “Forgive me, friends!” through tears and left. Of the about 300 of his classmates who had come to school that day, only 19 survived.

After traveling on foot and by train, late that night Mr. Kodama finally reached the house in Hesaka (now part of Higashi Ward) to which his family had relocated for safety. But one week later his hair and eyebrows began to fall out. He bled from his gums and the corners of his eyes and had a high fever of 42 degrees C. Purple spots appeared on his body. The doctor who came to the house to care for him didn’t think he would live, but in September his fever broke and his condition stabilized. “My mother brewed tea from dokudami [a medicinal plant] for me and rubbed roasted dokudami on the wounds that had festered. She put her heart and soul into nursing me. It was her love that kept me alive,” he said.

For years afterwards Mr. Kodama had no major illnesses, but in his 60s, one after another cancers were discovered, including cancer of the skin, rectum, stomach and thyroid gland. It was not a case of metastasis. Rather, multiple forms of cancer occurred simultaneously in different organs. Mr. Kodama had 19 operations, including 16 for skin cancer.

In September 2007, a test conducted at the Radiation Effects Research Foundation found that Mr. Kodama’s cells had chromosomal abnormalities as a result of the A-bombing. He was experiencing frequent chromosomal “translocations” in which a whole chromosome or a segment of a chromosome becomes attached to or interchanged with another chromosome or segment. In Mr. Kodama’s case this was occurring at an average of one translocation per cell, disrupting his genetic material and leading to cancer. He was told that this condition would not go away.

The test results indicated that Mr. Kodama had been exposed to about 4.6 gray of radiation, in excess of 4.0 gray, the amount regarded as a fifty percent lethal dose. This represents the amount at which half of those exposed would die within two months.

For many years Mr. Kodama never spoke about his A-bomb experiences. But he came to believe that, having survived, he had a duty to tell as many people as possible that nuclear weapons were inhumane. So he began telling his story. Now he shares his experiences and feelings with others who will continue to convey them as part of a program established by the City of Hiroshima to pass on survivors’ memories.

When telling of his experiences, he makes use of medical materials such as pictures of chromosomes. “I show objective data that illustrates that radiation harms people’s internal organs, and I try to explain things in a simple, persuasive manner,” he said.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Consider how to eliminate discrimination

I learned that many survivors were accused of being able to pass the harmful effects of radiation from the atomic bomb on to others, and it was difficult for many of them to get married or find a job once it became known that they were A-bomb survivors. I would have found that kind of treatment completely unacceptable. There was similar discrimination after the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima. I felt it was our mission to consider how to eliminate it. (Yoshiko Hirata, first-year junior high school student)

Expand circle of peace through conversation

Mr. Kodama talked about how the school building was instantly flattened by the atomic bomb and how the swimming pool at the school was full of students who had been burned. I could picture the terrible scene. He asked me to tell my family and friends about what I’d heard from him. When I told my mother, she listened carefully. I think that by listening and then thinking about what we have heard, the circle of peace will expand. (Kohei Hayashi, first-year high school student)

Learning about horror of continued impact

It was my first time to see a photo of the chromosomes of an atomic bomb survivor. There should be two identical chromosomes side by side, but in Mr. Kodama’s case, their lengths and shapes were different. I was really surprised. He said it’s a miracle that he is alive. He is still affected by the atomic bomb almost 70 years later. We must continue to emphasize that nuclear weapons must never be used again. (Ryo Kamiyasu, third-year high school student)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Mitsuo Kodama came to Kokutaiji High School to have his picture taken by the monument to the students of First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School. He pointed to each name and said things like this: “He was full of energy. I couldn’t save him.” “He wanted to be a doctor, so he went to medical school, but he had to give up his studies because he developed cataracts on account of the A-bombing.” His sorrow, regret and distress come across, and it was heart-wrenching. He sometimes seemed to be looking off into the distance, and I supposed he was alternately recalling good times with his classmates and the A-bombing.

When Mr. Kodama talks about the hardships he has suffered, including chromosomal abnormalities and multiple kinds of cancer, every word has an impact. But it’s not because he is wondering why all these things had to happen to him. Rather, it is his strong determination that we must all work together to eliminate inhumane weapons. Listening to him, I sensed the importance of what he had to say.

He told his story carefully, sometimes asking the junior high school-age junior writers, “Are you following me?” “If you look at the other person’s expression, it’s easy to tell whether or not you’re getting through,” he said. “It’s difficult to really get your message across.” What with the seriousness and powerful impact of Mr. Kodama’s story, after the interview I couldn’t do anything else for the rest of the day. But I was glad I to have been able to hear his story directly from him, and I felt I really wanted to tell my family and friends about it. That’s what Mr. Kodama is hoping for when he talks about passing on memories, and being able to make others feel that way is the result of Mr. Kodama’s expert ability to tell his story. (Daisuke Yamamoto)

◆Articles in the “Passing On Memories” are published occasionally and can be found in the “Survivors’ Stories” section of this website.

(Originally published on May 26, 2014)