History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 18, Article 2)

Mar. 9, 2013

The Early Days of the Campaign Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

The campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs, which fueled the peace movement in postwar Japan, arose as a nationwide, grassroots effort in 1954 in the wake of a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at the Bikini Atoll. A Japanese fishing boat known as the “Daigo Fukuryu Maru,” or “Lucky Dragon No. 5,” was exposed to the radioactive fallout from this nuclear blast.

A signature drive appealing for a ban on hydrogen bombs, launched by Tokyo housewives and fishmongers, spread swiftly. It also generated public interest in the A-bomb damage in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a subject which had been taboo under the U.S. occupation. Against the backdrop of the nuclear arms race unfolding between the United States and the Soviet Union, Japan’s peace movement began to take shape. Focusing on relief measures for A-bomb survivors, the movement demanded that there be no more incidents like Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Bikini anywhere else in the world.

How did the A-bomb experience and this experience of radiation exposure grow into the “nation’s experience and memory” through the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs, which was sparked by the Bikini Incident? The Chugoku Shimbun will take a fresh look at this history. Unlike today’s peace movement, which has hardened into factions along party lines, the movement in those years was imbued with the freewheeling force of life and the great energy of the postwar period.

Grassroots unity in opposition to atomic and hydrogen weapons

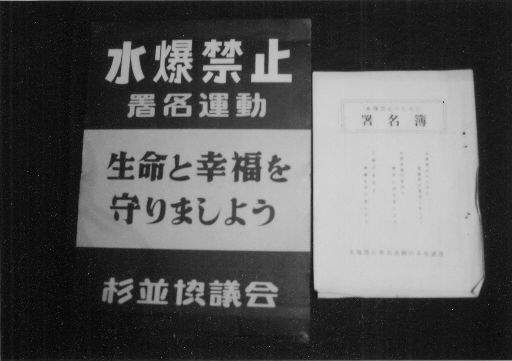

Legend has it that an unprecedented signature drive, in which 32.59 million people signed their names over the course of little more than a year to express their opposition to atomic and hydrogen bombs, was sparked by an appeal from a group of housewives in Suginami Ward, Tokyo.

Although this has become the prevailing story, it could better be described as historical lore. In truth, the signature drive against atomic and hydrogen bombs did not originate in Suginami nor was it an effort that occurred spontaneously.

We should not overlook the fact that, even during the U.S. occupation, those who responded to the campaign to collect signatures in support of the Stockholm Appeal, which called for the “outlawing of atomic weapons,” as well as peace activists from prewar days, were quick to take action.

One month before the group in Suginami was founded in May of 1954 to promote a ban on hydrogen bombs through its signature drive, 500 fishmongers and sushi dealers gathered at the auditorium in Tsukiji Market. As a consequence of the “A-bombed tuna,” the participants of the meeting had abruptly lost their customer base and they were grappling with ways to respond to the crisis. The gathering led to the launch of a campaign to collect signatures against atomic and hydrogen bombs and gain compensation for the losses they suffered.

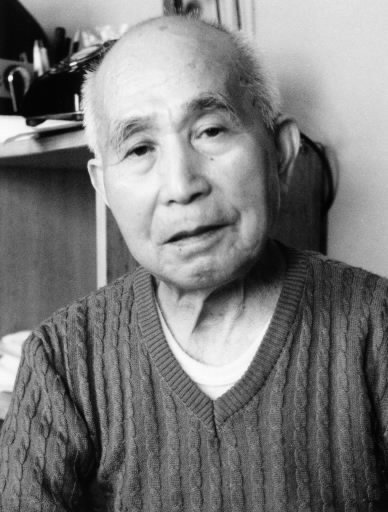

Kenichi Sugawara, 89, who was operating a Suginami fish shop called “Uoken,” coordinated the meeting and served as chair. Mr. Sugawara had been involved in the labor movement in Tokyo since before the war, when labor activities were still illegal.

“From printing leaflets, to distributing them, to mobilizing supporters... When it comes to a campaign, you definitely need experience,” Mr. Sugawara said. Making use of his tried and tested experience, he embarked on the signature drive locally. “At the time, the fishmongers were united in our aim to protect our livelihoods, and so we stood together regardless of party affiliation,” he explained. “It wasn’t just a one-sided campaign ‘against America.’ That’s why the campaign quickly gained momentum and spread.”

On April 17, in response to an appeal by Mr. Sugawara and others, as well as the signatures which had been solicited from in front of his fish shop, the Suginami City Assembly unanimously agreed to pass a resolution calling for a ban on hydrogen bomb tests. This groundwork paved the way for a signature drive throughout Suginami Ward from a base at the Suginami Community Center.

The Suginami Community Center opened in November 1953, the year before the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, a tuna fishing boat, was exposed to the radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at the Bikini Atoll. Kaoru Yasui, a professor at Hosei University who was known as a leading expert in international law, was serving as the part-time director of the facility.

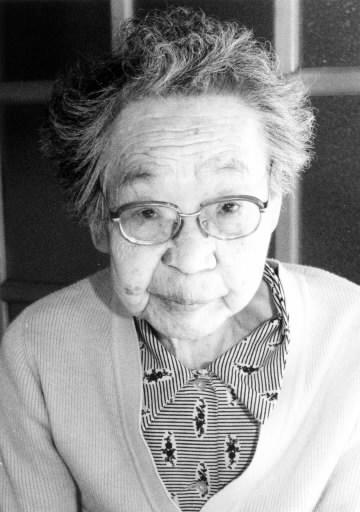

“With Professor Yasui as our guide, we gathered on the first Saturday of every month for a study session,” recalled Risoko Otsuka, now 84. “We read books on the social sciences and studied things like how the war began. Then the Bikini Incident took place. We were a group of housewives who wanted to do something, so we asked the professor for his advice about starting a signature drive.”

Ms. Otsuka was one of the 39 participants at the inaugural meeting of the group which launched the signature drive, called the “Suginami Council.” When I visited her in a quiet residential area that stretched along the Musashino Terrace, she explained the origins of the campaign. She was also a member of a women’s organization that lent its support to the effort to collect signatures backing the Stockholm Appeal.

The Suginami Council was established in May 1954, with Mr. Yasui serving as chair. The appeal this group issued, which later became known as the “Suginami Appeal” and led to Suginami’s reputation as the “birthplace of the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs,” was formulated through the discussions held at the Suginami Community Center, the hub for educational activities in the local area.

The appeal, which called on the people of Japan to “appeal to the whole world for a ban on hydrogen bombs through a signature drive involving the entire nation,” was emblematic of the nature of the movement against atomic and hydrogen bombs in those early days. As the Suginami Council itself declared: “This signature drive is not a campaign conducted by a particular political party, but a campaign for the whole nation which connects people from all walks of life.”

At the very first meeting of the Suginami Council, Mr. Yasui said that the group would not describe their efforts as part of the “peace movement,” explaining that the peace movement of the time was tarnished by the resistance activities against the occupying forces and the government. Mr. Yasui and the others were intent on pursuing a mass movement that anyone could feel free to join.

The freewheeling atmosphere of the postwar democracy and the fresh energy of the public at large continually infused the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs in the early days.

In records from that time, the names of people participating in the Suginami Council from the following groups can be found: “Suginoko-kai,” a women’s reading group at the Suginami Community Center; the Suginami branch of the Fisheries Cooperative; and the Ogikubo branch of the Construction Labor Union. Also to be found are the names of the president of the PTA of the junior high schools in Suginami Ward, who would later be the first administrative vice minister of the Science and Technology Agency, and a Liberal Party member of the Suginami City Assembly before the Liberal Democratic Party was born from the merger of the Liberal Party and the Japan Democratic Party. The sheer variety of people that converged for the campaign helped fuel the effort to collect signatures calling for hydrogen bombs to be banned.

The efforts made by women, who were in charge of their kitchens and had now been freed from men’s predominance, a notion of the prewar family system, were particularly remarkable.

For everything,

without taking myself into account,

I’ll look carefully, listen closely and understand well

and will not forget it.

Women rushed about in the spirit of this poem by Kenji Miyazawa which hung in the director’s office and begins with the phrase “Be not defeated by the rain.” These women took the initiative in collecting signatures and donations in the neighborhood, on the street, and in the schools their children attended. Returning to the community center, they used an abacus to total the signatures that had been gathered.

Just one month after the Suginami Council was formed, the signatures of 265,000 people, or as much as 68 percent of the population of that ward, had been collected.

With the public’s anxiety and fear stoked by the hydrogen bomb tests of that era--people were even afraid that fish would become inedible and death would be the result of getting caught in radioactive rain--the signature drive drew eager supporters. At the same time, the campaign was charged with this national sentiment of the postwar period: “We are fed up with war.”

And so, with the campaign in Suginami serving as a model, similar efforts to collect signatures came to life in other wards in Tokyo and in other locations in Japan. In July, Mr. Yasui, the Suginami leader, called for a national council to be formed to oversee the growing number of signature drives against atomic and hydrogen bombs.

Once the national council was established--composed of 12 representatives, including Dr. Hideki Yukawa and Mumeo Oku, president of the Japan Housewives’ Association--its administrative office became located at the Suginami Community Center and Mr. Yasui assumed the post of secretary general. By the end of that year, the number of signatures supporting a ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs had come to exceed 20 million and, in short order, led to the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs in Hiroshima in 1955, the following year.

Those who attended this international conference, from home and abroad, witnessed heartfelt appeals from survivors of the A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as islanders from the Bikini Atoll. They shared their experiences of the atomic bombings and exposure to radiation. The call for a ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs was now made by the united voice of the nation.

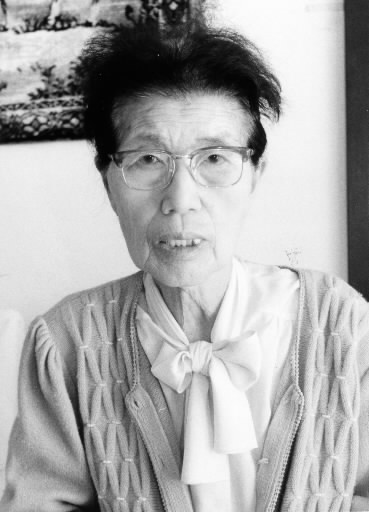

“I felt it was my duty to do something for the children,” said Tsuruko Saito, a resident of Nakano Ward, Tokyo. “When I joined the campaign, I felt nervous and excited. I realized keenly that appealing for a ban on nuclear weapons was the right thing to do. The campaign gave us a lot of freedom to take part as we saw fit.” Ms. Saito now serves as the director of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Peace Association, and even today, at the age of 85, is engaged in a citizen’s movement calling for the enactment of a law which would formalize Japan’s opposition to nuclear weapons.

However, the smooth trajectory of the movement against atomic and hydrogen bombs did not last for very long. In the 1960s, the movement splintered as a consequence of Socialist Party and Communist Party leaders vying for control. Ms. Otsuka, Mr. Sugawara, and Ms. Saito took separate paths, in line with their own convictions, and eventually left the movement itself.

Mr. Yasui, who also served as the first director of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, quoted the Kenji Miyazawa poem in his statement of resignation in 1963. The professor said: “The movement then was simple, but pure. It was brimming over with brightness. The selfless spirit found in the Suginami era [...] should be used to the best advantage.”

With political parties and their affiliated labor unions pursuing their own interests, the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs became detached from the general public. In 1989, the aging building that had housed the Suginami Community Center was torn down. Only a solitary monument, in remembrance of that era, now stands at the site.

Heiichi Fujii seeks relief measures for A-bomb survivors, proposes holding World Conference Against A- & H-Bombs in Hiroshima

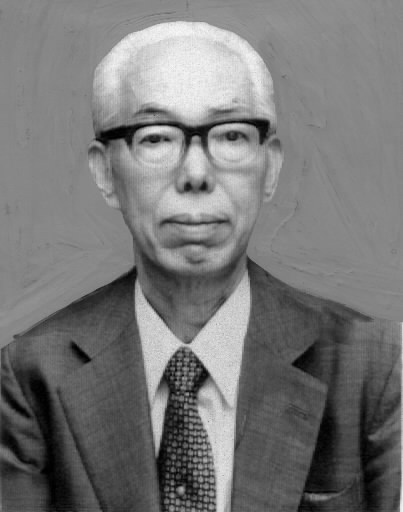

“Not just in Tokyo, but in Hiroshima, too, people were paying almost no attention to helping the A-bomb survivors.” Heiichi Fujii, 79, speaking from his home in downtown Hiroshima, described this lack of awareness shown by the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs during the early days. Mr. Fujii was the first secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations.

While the groundswell against hydrogen bombs surged in Suginami Ward, Tokyo, another signature drive was launched on its own in Hiroshima. The signatures of one million people from Hiroshima Prefecture, calling for a ban on the “production, testing, and use of atomic weapons,” were sent to the United Nations that September.

The head of a lumber company in Hiroshima, Mr. Fujii also served as the vice-chairman of the municipal federation of welfare commissioners and helped lead the appeal for the central government to cover the medical expenses of A-bomb survivors. In his eyes, the campaign that began with the mission of banning hydrogen bombs suffered a crucial oversight: the presence of A-bomb survivors and the pursuit of relief measures for them.

It was Mr. Fujii who proposed holding the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs in Hiroshima. He traveled to Tokyo a number of times and appealed for support in realizing the idea. Once the decision was made to hold the conference, he took on the task of managing the financial side to the event, a role that had found no takers during a planning session in Hiroshima.

“If A-bomb survivors had been excluded, it wouldn’t really be a campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs,” Mr. Fujii explained. “Still, even a member of our local committee said that if we included the survivors, they would stir up a fuss. The movement was focused only on banning the bombs.” The signature drives themselves were mainly Tokyo pursuits, in line with a Tokyo outlook.

Mr. Fujii and others moved to have relief measures for A-bomb survivors added to the conference agenda. They also created an opportunity for participants to be accommodated in private homes so they could hear, face to face, the personal accounts of A-bomb survivors. Such efforts eventually produced the “Hiroshima Appeal,” the declaration made at the conference, which called for relief measures for the survivors of atomic and hydrogen bombs.

Shortly after the conference, Yoshio Nakano, a professor at the University of Tokyo and a pillar of Japan’s democratic movement in the postwar era, wrote about the campaign seeking to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs and the involvement of A-bomb survivors: “I now reflect on the fact that, as I had supposed, we only grasp this problem from a distance.”

In August of the following year, the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations was born.

(Originally published on May 21, 1995)