History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 2, Article 1)

Aug. 1, 2012

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park stretches across the center of a delta in Hiroshima, a city of rivers, with Peace Boulevard running alongside the park. When standing on the 100-meter-wide boulevard, facing Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and the Atomic Bomb Dome can be seen standing along a straight axis to the north. From that spot, when silence prevails, the cry of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima can be heard.

This is where the hypocenter lies, where a single atomic bomb annihilated everything. From utter ruin, the site was transformed into the park, with an area of some 122,000 square meters, and its memorial facilities, becoming a place for the vow of seeking a lasting peace.

Two young artists, Kenzo Tange and Isamu Noguchi--Japanese and American, respectively--devoted all their skill and passion to realizing this grand project. However, the effort to construct the park was buffeted by public opinion and the passions of the day. Meanwhile, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony was marked by pressure exerted by the occupying forces. In this article, the Chugoku Shimbun will explore part of the untold history involving the rebirth of Hiroshima as the A-bombed city, including the appeals that lay behind this rebirth.

A-bomb memorial by Isamu Noguchi left unfulfilled

Michio Noguchi, 63, is the younger brother of Isamu Noguchi. Michio lingered at the foot of Peace Bridge, a structure which Isamu designed, and recalled the past: “Isamu had a Japanese father and an American mother and he dreamed of creating an A-bomb memorial for the city of Hiroshima. The fact that his design wasn't adopted made him very depressed, especially since his feelings for the monument he had designed were so special and strong.”

Isamu Noguchi was an internationally-known sculptor who died in New York in 1988 at the age of 84. He was active in a range of artistic areas, including stage design for the theater, and his work in landscape gardening included the Japanese garden for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Paris. His marriage to actress Yoshiko Yamaguchi (now, Yoshiko Otaka and 74) was big news in post-war Japan.

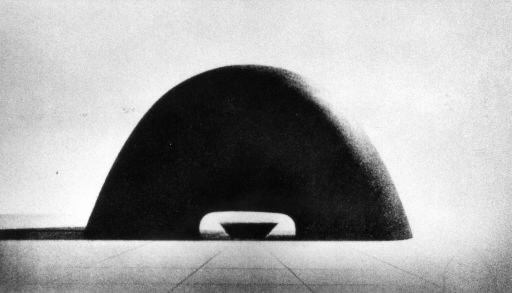

In 1951, Isamu designed the railings for the Peace Bridge and the western Peace Bridge, which lead to Peace Memorial Park. At the same time, he worked on his “Memorial to the Dead of Hiroshima” for the victims of the atomic bombing. The design was inspired by Haniwa, terracotta clay figures made for rituals and buried with the dead as funerary objects during the Tumulus Period. However, his memorial idea would finally not be realized.

Isamu was born in Los Angeles to Yonejiro Noguchi, a Japanese poet who also gained a reputation in the field of British and American literature, and Léonie Gilmour, an American writer. When he was two years old, his mother took him to Japan, where his father was living. However, his father, who was a professor at Keio University, had taken a new wife. At the age of 13, Isamu returned by himself to the United States. Later, while studying medicine at Columbia University, he felt a calling to become a sculptor and, in 1927, he traveled to Paris.

“He was the epitome of a free man, unbound by race or nationality. World War II reinforced that way of thinking in him,” said Joji Sadao, 67, who runs the Noguchi Museum in New York, as he described Isamu's attitude toward the world, fostered since his childhood.

When an order for the relocation of all 110,000 Japanese-Americans who lived on the west coast of the United States was issued following the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, Isamu voluntarily came from the eastern side of the country to Arizona and the Poston Relocation Center, situated amidst a bleak and sprawling desert. Through art activities, he sought to relieve the harsh environment of the internment camp.

Yoshiko Yamaguchi, in her memoir entitled “Ri Koran: Watashi no Hansei” (“Half My Life as Ri Koran”), plainly described the hidden scarring that lay deep within Isamu: “I was touched deeply by his words 'You must have had a hard time during the war between Japan and China. It was an agonizing time for me, too, when Japan and the United States were at war.'”

Tsutomu Hiroi, 70, Ms. Yamaguchi’s younger brother-in-law, who is a sculptor and a professor at Atomi University, was involved in Isamu's work. In 1950, when Isamu came to Japan again, he had already made a name for himself in the world. Mr. Hiroi, serving as Isamu's assistant, accompanied him to the construction site of Peace Bridge, and also took part in the effort to design the memorial for the A-bomb victims.

“Isamu was in high spirits about the project,” Mr. Hiroi said. “He was enthusiastic about it. At the time, Mr. Tange was an associate professor at the University of Tokyo and Isamu and I were working together in his classroom, making a series of plaster models of his idea. But we ran up against interference from outside...”

For projects connected to the creation of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, a stamp of approval was needed from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Committee, a committee of experts. On that committee were ten people, including an adviser to the Economic Stabilization Board and a professor at the University of Tokyo, who was a leading figure in the field of architecture.

Revealing why Isamu Noguchi's design for the memorial was rejected by the committee, his brother Michio said, “One of the committee members felt it was unacceptable to use a design made by someone from the nation that dropped the atomic bomb. Mr. Tange became caught between this view and Isamu. In the end, he could only apologize to Isamu, going to his knees and begging his forgiveness. 'I can't do anything about it on my own,' he said.” Michio avoided mentioning the committee member by name.

“As an artist of Japanese and American descent, inheriting the culture of both nations, I would like to create a memorial for the city of Hiroshima, in part to make amends for the atomic bomb, which was dropped by my mother's nation.” The enthusiasm Isamu expressed for the project was ultimately undone as a consequence of his American citizenship.

In 1953, Isamu Noguchi said in the American magazine “Arts and Architecture” that, although a memorial for the A-bomb victims was intended as a symbol for all people to recognize and reflect on the tragedy, assistance from non-Japanese was deemed unnecessary. Still, his desire to create the “Memorial to the Dead of Hiroshima” grew stronger. He sought a place to erect the monument in Washington, D.C. and in the vicinity of United Nations headquarters in New York. However, he was unable to realize this wish. If the memorial had been built, it would have been made of black granite, standing six meters tall.

Today, as part of its effort marking the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, the City of Hiroshima is conducting a comprehensive review of Peace Boulevard in response to growing traffic and the planned Subway Tozai Line (a tentative name). The rebuilding of Peace Bridge and the western Peace Bridge, both of which are 15 meters wide and symbols of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, has become an issue for consideration.

Michio Noguchi came to Hiroshima from Tokyo at the end of last year to join the discussion. He appealed to the City of Hiroshima: “Isamu designed the railings of these bridges exclusively for Hiroshima. I hope the city will preserve his spirit, even in the form of a replica.”

Since the 1970s, Isamu Noguchi had maintained a studio in the town of Mure in Kagawa Prefecture. Until his death, he continued his work in Japan, the United States, and Europe.

Isamu always said, sometimes on a bittersweet note, that national borders were the worst thing in the world, because the world was one.

A-bomb Dome is heart of design by Kenzo Tange for Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

“The atomic bombing shocked me, as I spent my high school days in Hiroshima, away from my hometown of Imabari in Ehime Prefecture,” said Mr. Tange, 81. “When the War Damage Rehabilitation Board [now, the Ministry of Works] called for an inquiry into the reconstruction of Hiroshima, I raised my hand without hesitation, though some said that the participants would end up suffering from A-bomb disease.”

The office of Kenzo Tange's “Urbanists and Architects Team” overlooks the Crown Prince’s Palace in Akasaka, Tokyo. Mr. Tange received the Order of Culture in 1980 and a Commandeur in the French Order of Arts and Letters, among other prizes. But in the fall of 1946, Mr. Tange was 33 years old and an associate professor in the Department of Architecture at the University of Tokyo. Arriving in Hiroshima, he traveled about the ruins of the city in a car with a wood gas generator.

“Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai was enthusiastic about the idea of creating a park out of the hypocenter area,” Mr. Tange said. “I don't remember which one of us first made the suggestion, but we agreed that the land north of Peace Boulevard would be a suitable site for the park. Though some were saying that the A-bomb Dome should be torn down, I felt that peace could be brought about only if we understood the horror and devastation wrought by the atomic bomb. This is why I used the A-bomb Dome as the heart of my design for Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.”

In 1949, the City of Hiroshima staged a competition for the design of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. From the 145 applications, the design made by Mr. Tange and three members of his office at the University of Tokyo was selected. The prize money was 70,000 yen. At that time a plate of curry and rice cost 50 yen.

“Our plan presented the idea of building a large arch, with a bell suspended from it, in the center of the park and through the arch the A-bomb Dome could be seen from Peace Boulevard,” Mr. Tange explained. “However, the city did not have enough funds to realize the original plan. And since a similar arch was erected in the U.S. city of St. Louis prior to our project, we felt that a smaller memorial would be fine and so we ended up building the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims.”

The construction of the two Peace Bridges, which lie east and west of Peace Boulevard, began in 1950 with U.S. funds made available for Japan. The railings of these bridges were designed by sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

Mr. Tange recalled: “The Chugoku Regional Development Bureau of the Ministry of Works asked me to design the bridges. When I spoke to Isamu, who was in Japan at the time, he said he was very interested in designing the bridges. Though there was a silly controversy over its artistic merits in the city assembly, the project by Isamu went forward. Up to that point, everything was going well...”

He went on: “I felt that Isamu should be the one to design the memorial for the A-bomb victims. But maybe I was too naïve in my thinking. As it turned out, there was a strong voice who said that it was wrong to let Americans, who dropped the bomb, design the memorial, and that the Japanese should create it. I tried to persuade the committee that oversaw the project, but to no avail. From the beginning, though, I had also thought that a terracotta clay figure could serve as the inspiration for the shape of the cenotaph.”

In 1994, three memorial facilities in the park were linked by connecting corridors in line with the original plan, with Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in the center. Meanwhile, a hotel designed by a third party was built in the park, where the International Conference Center Hiroshima now stands.

“Though a few odd buildings were in the area, people gradually transformed the park into an ideal place to make an appeal for peace,” Mr. Tange said. “The atomic bomb was an awful thing. We don’t want something so inhumane. I think the park and its environs teach these lessons.”

In 1979, Mr. Tange proposed that the center of Peace Boulevard be turned into a grassy area and its side road be turned into a roadway. The City of Hiroshima is now considering the idea of enhancing Peace Boulevard's use as a main thoroughfare.

“As long as it's called Peace Boulevard, it's not simply a road,” Mr. Tange said. “I can’t fully agree with the idea of widening the roadway that runs in the center of Peace Boulevard. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and the boulevard form the heart of the A-bombed city. When I went abroad for the first time in 1951, and shared the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction project, I was asked if such an idea was really possible. No other place in the world is like Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, where wishes for peace are embodied in complete harmony. I think we can be proud of that area.”

(Originally published on January 29, 1995)