Shoso Kawamoto, 78, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Jan. 15, 2013

His mother told him: “Don’t give up”

Looking for a place to die, his life was reborn

Shoso Kawamoto, 78, lost six members of his family—his parents and siblings—to the atomic bombing. But the words his mother Satsuki often said to him when she was alive became his anchor, enabling him to endure his hardships after the war: “Don’t give up.”

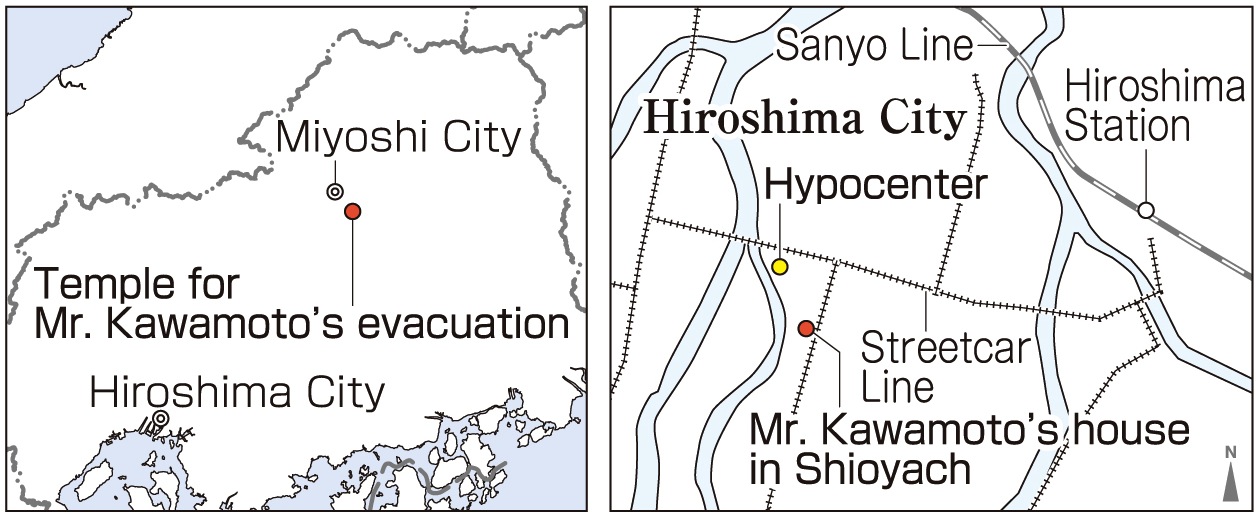

When the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945, Mr. Kawamoto was a sixth grader at Fukuromachi National School (present-day Fukuromachi Elementary School in Naka Ward). His house was located in Shioyacho (part of today’s Naka Ward), near the hypocenter, but he had been evacuated with other schoolchildren to a temple in the village of Kamisugi (now part of Miyoshi City), north of Hiroshima, before the bombing took place. That day, while working in a field, he noticed a white cloud rising in the sky in the direction of Hiroshima.

In the evening, he learned that the city center had been completely destroyed. Three days later, Tokie, a sister who was five years older and had been working at Hiroshima Station when the atomic bomb exploded, came to the temple to pick him up.

Tokie told him that their mother and younger siblings had died at home, embracing one another. The whereabouts, however, of his father and another elder sister, who were both helping to dismantle homes to create a fire lane, were unknown. Even to this day, they are unaccounted for.

After the war, Mr. Kawamoto lived with Tokie in the vicinity of Hiroshima Station. But Tokie died of leukemia in February 1946. After that, he became a live-in worker, helping to make soy sauce in the Tomo district (part of present-day Asaminami Ward).

At the age of 23, he proposed marriage to a woman. Though his heart was set on marrying her, her parents expressed concern about the children they would bear and rebuffed his proposal. “We can’t let our daughter marry an atomic bomb survivor,” they told him. Mr. Kawamoto felt as if his whole world had turned black. He decided to live alone and he fled the soy sauce maker.

He drifted from job to job at a series of transportation companies, gambling away most of his wages. In his early 30s, he was unable to pay a 2,000-yen traffic ticket and so he lost his driver’s license. As a result, he could no longer work at his place of employment, and he saw no reason to go on living. Looking for a place to end his misery, he boarded a train and sought to go as far as he could with 640 yen, all the money he had.

He got off the train at Okayama Station, in the city of Okayama, and saw a poster in front of the station calling for live-in workers at a noodle shop. Gazing at the poster, he thought he heard his mother’s voice telling him, “You can do it. Don’t give up.” And so, at that moment, he found the determination to start his life over again.

At the age of 50, he became president of a food service company. Then, when he turned 70, a friend from his elementary school days contacted him and said, “We’ve all been worried about you.” These words made him miss Hiroshima, and so he finally returned to his hometown.

Mr. Kawamoto now serves as a guide at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and shares his account of the atomic bombing to visitors there. He also makes paper airplanes in the way his mother once taught him and distributes these airplanes along with a paper crane. To date, he has given away some 70,000 paper airplanes and cranes.

In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, he came across many A-bomb orphans in front of Hiroshima Station who were forced to choose between helping criminal gangs to survive or dying from hunger. These children were unable to play or go to school, even if they wanted to. “I don’t want young people today to face the same kind of suffering,” he said. “I want people to know the hardship that the atomic bomb produced.” His wishes, imbued in his paper cranes, are now spreading their wings in the world.

Paper cranes: made famous by a girl named Sadako

Legend has it that if you fold 1,000 paper cranes, your wish will come true. As a result of the fate of a girl named Sadako Sasaki, the inspiration for the Children’s Peace Monument which now stands in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, the paper crane has also become a symbol of peace. Sadako died of leukemia at the age of 12, ten years after the bombing. The illness was induced by the A-bomb’s radiation.

While hospitalized at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, Sadako received a gift of paper cranes from a high school in Nagoya. It was this that prompted her to start folding paper cranes, hoping to regain her health.

After she died, her classmates began a campaign to erect a monument, wanting to “comfort the souls of all the children who died in the atomic bombing.” This campaign gained widespread support and the monument was unveiled in 1958.

The story of Sadako and her paper cranes has been conveyed to the world through books and movies. Ariyuki Fukushima, 37, a curator at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, said, “Paper cranes are now endowed with a variety of meanings, such as the earnest hope to live or the resistance to things that are unjust.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

I realized the importance of education

I was shocked to hear that he lost his family when he was 11 years old and was on his own after that. Because he had to work, and couldn’t go to school, he studied books to learn kanji. He stressed to us the importance of studying, saying, “I want you to be aware of the importance of education.” I feel blessed that I’m able to study like I can. I plan to study hard and realize my dreams. (Risa Murakoshi, 16)

I thought about how I’ve wasted food

From Mr. Kawamoto’s story, I learned about the lives of the A-bomb orphans for the first time. He told us that some orphans would suck on small stones to try to quiet their hunger. It made me think about my own actions, and how I’ve left foods that I don’t like on my plate without thinking very deeply about it.

There are still a lot of things about the atomic bombing that I don’t know. I want to learn more about it. (Nene Takahashi, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

I visited the area in front of Hiroshima Station with Mr. Kawamoto. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, as Mr. Kawamoto was living in that area with his older sister, he saw many A-bomb orphans who were struggling to survive. He recalled how he collected scrap iron to earn money for orphaned friends who had fallen in with gangsters.

As we were walking through the area, a woman who appeared to be in her 80s approached us and said that she began a business there after the war ended. When Mr. Kawamoto told her that he had lived in the shadow of the station then, she was nearly in tears and said, “You were living here? I’m sorry I wasn’t able to do anything for you. I’m glad that you managed to survive.”

She may have been remembering scenes of children who died of starvation, alone, or sucked on small stones to ward off their hunger.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum displays only one panel with information about the A-bomb orphans. Mr. Kawamoto therefore wanted to tell the true story in his own words and so he registered at the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation to serve as a Hiroshima Peace Volunteer, working as a guide in Peace Memorial Museum and Peace Memorial Park, and as a speaker delivering his A-bomb account. Mr. Kawamoto performs his volunteer service every Thursday, so if you happen to visit the museum that day, you might have the opportunity to meet him. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on December 24, 2012)

Looking for a place to die, his life was reborn

Shoso Kawamoto, 78, lost six members of his family—his parents and siblings—to the atomic bombing. But the words his mother Satsuki often said to him when she was alive became his anchor, enabling him to endure his hardships after the war: “Don’t give up.”

When the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945, Mr. Kawamoto was a sixth grader at Fukuromachi National School (present-day Fukuromachi Elementary School in Naka Ward). His house was located in Shioyacho (part of today’s Naka Ward), near the hypocenter, but he had been evacuated with other schoolchildren to a temple in the village of Kamisugi (now part of Miyoshi City), north of Hiroshima, before the bombing took place. That day, while working in a field, he noticed a white cloud rising in the sky in the direction of Hiroshima.

In the evening, he learned that the city center had been completely destroyed. Three days later, Tokie, a sister who was five years older and had been working at Hiroshima Station when the atomic bomb exploded, came to the temple to pick him up.

Tokie told him that their mother and younger siblings had died at home, embracing one another. The whereabouts, however, of his father and another elder sister, who were both helping to dismantle homes to create a fire lane, were unknown. Even to this day, they are unaccounted for.

After the war, Mr. Kawamoto lived with Tokie in the vicinity of Hiroshima Station. But Tokie died of leukemia in February 1946. After that, he became a live-in worker, helping to make soy sauce in the Tomo district (part of present-day Asaminami Ward).

At the age of 23, he proposed marriage to a woman. Though his heart was set on marrying her, her parents expressed concern about the children they would bear and rebuffed his proposal. “We can’t let our daughter marry an atomic bomb survivor,” they told him. Mr. Kawamoto felt as if his whole world had turned black. He decided to live alone and he fled the soy sauce maker.

He drifted from job to job at a series of transportation companies, gambling away most of his wages. In his early 30s, he was unable to pay a 2,000-yen traffic ticket and so he lost his driver’s license. As a result, he could no longer work at his place of employment, and he saw no reason to go on living. Looking for a place to end his misery, he boarded a train and sought to go as far as he could with 640 yen, all the money he had.

He got off the train at Okayama Station, in the city of Okayama, and saw a poster in front of the station calling for live-in workers at a noodle shop. Gazing at the poster, he thought he heard his mother’s voice telling him, “You can do it. Don’t give up.” And so, at that moment, he found the determination to start his life over again.

At the age of 50, he became president of a food service company. Then, when he turned 70, a friend from his elementary school days contacted him and said, “We’ve all been worried about you.” These words made him miss Hiroshima, and so he finally returned to his hometown.

Mr. Kawamoto now serves as a guide at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and shares his account of the atomic bombing to visitors there. He also makes paper airplanes in the way his mother once taught him and distributes these airplanes along with a paper crane. To date, he has given away some 70,000 paper airplanes and cranes.

In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, he came across many A-bomb orphans in front of Hiroshima Station who were forced to choose between helping criminal gangs to survive or dying from hunger. These children were unable to play or go to school, even if they wanted to. “I don’t want young people today to face the same kind of suffering,” he said. “I want people to know the hardship that the atomic bomb produced.” His wishes, imbued in his paper cranes, are now spreading their wings in the world.

Hiroshima Insight

Paper cranes: made famous by a girl named Sadako

Legend has it that if you fold 1,000 paper cranes, your wish will come true. As a result of the fate of a girl named Sadako Sasaki, the inspiration for the Children’s Peace Monument which now stands in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, the paper crane has also become a symbol of peace. Sadako died of leukemia at the age of 12, ten years after the bombing. The illness was induced by the A-bomb’s radiation.

While hospitalized at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, Sadako received a gift of paper cranes from a high school in Nagoya. It was this that prompted her to start folding paper cranes, hoping to regain her health.

After she died, her classmates began a campaign to erect a monument, wanting to “comfort the souls of all the children who died in the atomic bombing.” This campaign gained widespread support and the monument was unveiled in 1958.

The story of Sadako and her paper cranes has been conveyed to the world through books and movies. Ariyuki Fukushima, 37, a curator at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, said, “Paper cranes are now endowed with a variety of meanings, such as the earnest hope to live or the resistance to things that are unjust.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

I realized the importance of education

I was shocked to hear that he lost his family when he was 11 years old and was on his own after that. Because he had to work, and couldn’t go to school, he studied books to learn kanji. He stressed to us the importance of studying, saying, “I want you to be aware of the importance of education.” I feel blessed that I’m able to study like I can. I plan to study hard and realize my dreams. (Risa Murakoshi, 16)

I thought about how I’ve wasted food

From Mr. Kawamoto’s story, I learned about the lives of the A-bomb orphans for the first time. He told us that some orphans would suck on small stones to try to quiet their hunger. It made me think about my own actions, and how I’ve left foods that I don’t like on my plate without thinking very deeply about it.

There are still a lot of things about the atomic bombing that I don’t know. I want to learn more about it. (Nene Takahashi, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

I visited the area in front of Hiroshima Station with Mr. Kawamoto. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, as Mr. Kawamoto was living in that area with his older sister, he saw many A-bomb orphans who were struggling to survive. He recalled how he collected scrap iron to earn money for orphaned friends who had fallen in with gangsters.

As we were walking through the area, a woman who appeared to be in her 80s approached us and said that she began a business there after the war ended. When Mr. Kawamoto told her that he had lived in the shadow of the station then, she was nearly in tears and said, “You were living here? I’m sorry I wasn’t able to do anything for you. I’m glad that you managed to survive.”

She may have been remembering scenes of children who died of starvation, alone, or sucked on small stones to ward off their hunger.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum displays only one panel with information about the A-bomb orphans. Mr. Kawamoto therefore wanted to tell the true story in his own words and so he registered at the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation to serve as a Hiroshima Peace Volunteer, working as a guide in Peace Memorial Museum and Peace Memorial Park, and as a speaker delivering his A-bomb account. Mr. Kawamoto performs his volunteer service every Thursday, so if you happen to visit the museum that day, you might have the opportunity to meet him. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on December 24, 2012)