Hiroso Niimi, 73, Naka Ward, Hiroshima

Dec. 7, 2012

Recalling the sight of his mother, trapped and bleeding

“Run away!” she screamed from under the wreckage of their house

“Hiro, hurry! Run away!” It was just after the atomic bomb exploded and Hiroso Niimi’s mother, trapped under their toppled home, was screaming at him to flee. Mr. Niimi, now 73, still vividly recalls the sight of his mother’s face, red with blood, through a gap between the fallen beams.

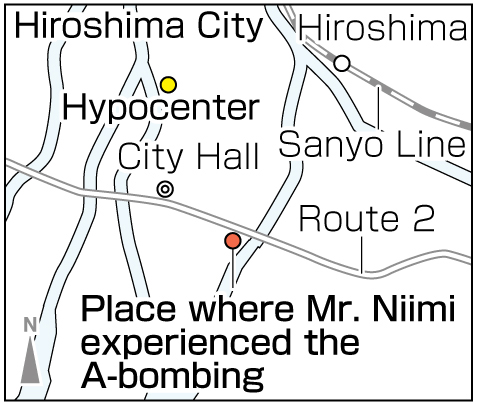

Mr. Niimi was 6 years old that morning of August 6, 1945. He was at home in Hiranocho (part of present-day Naka Ward), about 1.7 kilometers from the A-bomb’s hypocenter. He had changed into his clothes and was getting ready to head out to the hospital because he was having some trouble with his right eye.

He doesn’t remember the bomb’s flash or roar when it exploded at 8:15 a.m. When he regained his senses, he found that he had been blown into the yard. Some fragments of glass had pierced his body, and he suffered burns and cuts. Though he wanted to stay and help his mother, his uncle, who was living with them, urged him to flee with his aunt and cousin.

They fled with a wave of other survivors to a shrine in Ujina (part of present-day Minami Ward). Along the way, he saw the bodies of victims who had been burned black or were covered in blood.

Several days later, a soldier heading to help cremate bodies led him to a place about one kilometer from his house. There, a neighbor told him that his mother had been spotted, and this raised the hope that she hadn’t burned to death after all, that she somehow survived.

He returned to the place where his house had stood and found a message written on a roof tile. It was from his father, who had been safely away on a business trip to Okayama when Hiroshima was attacked. The message said he was now at Senda National School (now Senda Elementary School in Naka Ward).

The next day Mr. Niimi was reunited with his father and older brother near the school. He was then brought to see his mother. Her wounded face was shrouded in bandages, but he recognized her voice and the form of her body. The happiest moment of his life was when his mother embraced him. He learned that she had been aided by his uncle, who stayed behind when he fled, and also a passerby.

After the bombing, he endured many hardships. He ate horseweed, something no one eats today, and went fishing and clamming in a river that still held bodies of the victims.

He went on to become a national public servant and held staff positions at Hiroshima University, Kobe University, and Yamaguchi University. After marrying, his first son was born in 1966, but then he developed cancer. Though the cancer went into remission, Mr. Niimi has long been anxious about his health and is now battling two types of cancer.

“As an atomic bomb survivor, I was blessed to survive, so I want to convey the misery of the atomic bombing to others,” he said. In 2008, Mr. Niimi became a Hiroshima Peace Volunteer and now serves as a guide at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. In 2009, he took part in a project organized by Peace Boat, a Tokyo-based NGO, in which survivors shared their A-bomb accounts during an around-the-world voyage. At each port of call, he urged people to visit Hiroshima.

“Learn about Hiroshima’s past and think about what you can do for peace, then take action,” Mr. Niimi said. “This isn’t just somebody else’s business. It’s your business, too.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Peace Volunteers serve as guides to Peace Memorial Museum and Peace Memorial Park

The Hiroshima Peace Volunteers provide free guides to Peace Memorial Museum and Peace Memorial Park. In 1999, the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, which oversees the museum, established a registry of volunteers to hand down the reality of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.

Volunteers must be at least 18 years of age and available to work at least twice a month. After undergoing training, they can then serve as guides. As of April 1, 2012, 197 volunteers from the ages of 21 to 85 have joined the registry and 10-15 people are working as guides each day. Some volunteers also serve as guides in English, Chinese, and sign language.

Keiko Ogawa, 65, lives in the city of Hatsukaichi and became a Hiroshima Peace Volunteer five years ago. At the museum, when she sees students from elementary school through high school, she approaches them and explains about A-bomb orphans, whose parents were killed in the bombing. “When they imagine such a thing happening to themselves, their faces become very solemn,” she said. “I want to convey to them the importance of peace.”

The volunteers wear green jackets in the winter and green shirts in the summer. If you see a Hiroshima Peace Volunteer, don’t hesitate to ask them questions about the atomic bombing. You can also reserve a guide in advance.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to think about what I can do for peace

After the atomic bombing, Mr. Niimi caught fish and found clams in the river, where there were still bodies, and had to walk a long way to get food. Those things left a strong impression on me.

He stressed to us, over and over, that “It’s vital to know about Hiroshima.” I want to understand the spirit of the people who worked to reconstruct the city and think about what I can do for peace. (Kantaro Matsuo, 14)

I was shocked at his story and his tears

I was shocked to see the tears flowing down Mr. Niimi’s face when he told us how he fled along the road strewn with the bodies of A-bomb victims.

Still, I found it moving that he was able to share such painful experiences during the voyage that took him around the world, even when he was battling illness. Now it’s our turn to hand down the horror and misery of the atomic bombing. (Issei Nishizaki, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

One day during a heat wave this past August, I called Mr. Niimi and asked if he would tell his story for the newspaper, but I learned that he was about to be hospitalized. I was worried about him, but after undergoing surgery to combat his cancer, he returned from the hospital and was eager to sit for an interview.

Despite battling illness, he feels a sense of mission as someone who managed to survive the atomic bombing, and so is actively sharing his A-bomb account. To the teens who accompanied me, he stressed, “I’d like you to think about what peace is. Don’t take our peaceful life today for granted.

The average age of the A-bomb survivors has now risen to more than 78 years old. We must embrace the hearts of survivors and listen to them closely. There is little time left to hear their stories. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on November 26, 2012)

“Run away!” she screamed from under the wreckage of their house

“Hiro, hurry! Run away!” It was just after the atomic bomb exploded and Hiroso Niimi’s mother, trapped under their toppled home, was screaming at him to flee. Mr. Niimi, now 73, still vividly recalls the sight of his mother’s face, red with blood, through a gap between the fallen beams.

Mr. Niimi was 6 years old that morning of August 6, 1945. He was at home in Hiranocho (part of present-day Naka Ward), about 1.7 kilometers from the A-bomb’s hypocenter. He had changed into his clothes and was getting ready to head out to the hospital because he was having some trouble with his right eye.

He doesn’t remember the bomb’s flash or roar when it exploded at 8:15 a.m. When he regained his senses, he found that he had been blown into the yard. Some fragments of glass had pierced his body, and he suffered burns and cuts. Though he wanted to stay and help his mother, his uncle, who was living with them, urged him to flee with his aunt and cousin.

They fled with a wave of other survivors to a shrine in Ujina (part of present-day Minami Ward). Along the way, he saw the bodies of victims who had been burned black or were covered in blood.

Several days later, a soldier heading to help cremate bodies led him to a place about one kilometer from his house. There, a neighbor told him that his mother had been spotted, and this raised the hope that she hadn’t burned to death after all, that she somehow survived.

He returned to the place where his house had stood and found a message written on a roof tile. It was from his father, who had been safely away on a business trip to Okayama when Hiroshima was attacked. The message said he was now at Senda National School (now Senda Elementary School in Naka Ward).

The next day Mr. Niimi was reunited with his father and older brother near the school. He was then brought to see his mother. Her wounded face was shrouded in bandages, but he recognized her voice and the form of her body. The happiest moment of his life was when his mother embraced him. He learned that she had been aided by his uncle, who stayed behind when he fled, and also a passerby.

After the bombing, he endured many hardships. He ate horseweed, something no one eats today, and went fishing and clamming in a river that still held bodies of the victims.

He went on to become a national public servant and held staff positions at Hiroshima University, Kobe University, and Yamaguchi University. After marrying, his first son was born in 1966, but then he developed cancer. Though the cancer went into remission, Mr. Niimi has long been anxious about his health and is now battling two types of cancer.

“As an atomic bomb survivor, I was blessed to survive, so I want to convey the misery of the atomic bombing to others,” he said. In 2008, Mr. Niimi became a Hiroshima Peace Volunteer and now serves as a guide at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. In 2009, he took part in a project organized by Peace Boat, a Tokyo-based NGO, in which survivors shared their A-bomb accounts during an around-the-world voyage. At each port of call, he urged people to visit Hiroshima.

“Learn about Hiroshima’s past and think about what you can do for peace, then take action,” Mr. Niimi said. “This isn’t just somebody else’s business. It’s your business, too.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Hiroshima Peace Volunteers serve as guides to Peace Memorial Museum and Peace Memorial Park

The Hiroshima Peace Volunteers provide free guides to Peace Memorial Museum and Peace Memorial Park. In 1999, the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, which oversees the museum, established a registry of volunteers to hand down the reality of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.

Volunteers must be at least 18 years of age and available to work at least twice a month. After undergoing training, they can then serve as guides. As of April 1, 2012, 197 volunteers from the ages of 21 to 85 have joined the registry and 10-15 people are working as guides each day. Some volunteers also serve as guides in English, Chinese, and sign language.

Keiko Ogawa, 65, lives in the city of Hatsukaichi and became a Hiroshima Peace Volunteer five years ago. At the museum, when she sees students from elementary school through high school, she approaches them and explains about A-bomb orphans, whose parents were killed in the bombing. “When they imagine such a thing happening to themselves, their faces become very solemn,” she said. “I want to convey to them the importance of peace.”

The volunteers wear green jackets in the winter and green shirts in the summer. If you see a Hiroshima Peace Volunteer, don’t hesitate to ask them questions about the atomic bombing. You can also reserve a guide in advance.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to think about what I can do for peace

After the atomic bombing, Mr. Niimi caught fish and found clams in the river, where there were still bodies, and had to walk a long way to get food. Those things left a strong impression on me.

He stressed to us, over and over, that “It’s vital to know about Hiroshima.” I want to understand the spirit of the people who worked to reconstruct the city and think about what I can do for peace. (Kantaro Matsuo, 14)

I was shocked at his story and his tears

I was shocked to see the tears flowing down Mr. Niimi’s face when he told us how he fled along the road strewn with the bodies of A-bomb victims.

Still, I found it moving that he was able to share such painful experiences during the voyage that took him around the world, even when he was battling illness. Now it’s our turn to hand down the horror and misery of the atomic bombing. (Issei Nishizaki, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

One day during a heat wave this past August, I called Mr. Niimi and asked if he would tell his story for the newspaper, but I learned that he was about to be hospitalized. I was worried about him, but after undergoing surgery to combat his cancer, he returned from the hospital and was eager to sit for an interview.

Despite battling illness, he feels a sense of mission as someone who managed to survive the atomic bombing, and so is actively sharing his A-bomb account. To the teens who accompanied me, he stressed, “I’d like you to think about what peace is. Don’t take our peaceful life today for granted.

The average age of the A-bomb survivors has now risen to more than 78 years old. We must embrace the hearts of survivors and listen to them closely. There is little time left to hear their stories. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on November 26, 2012)