Sayoko Fujioka, 89, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Aug. 10, 2012

Hawaiian-born, A-bombed in Hiroshima

Daughter’s death at six months leaves brief memories

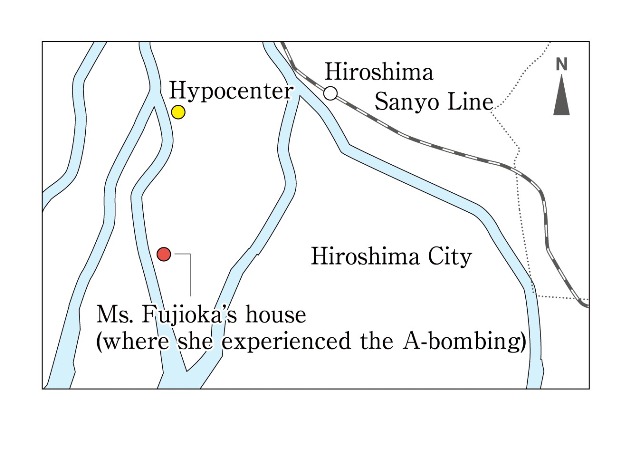

Sayoko Fujioka (nee, Morikubo), 89, was born and raised in the United States, in Hawaii. At the age of 14, she moved to Hiroshima, her father’s hometown. She was 22 when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. She experienced the bombing in the Sendamachi district, part of today’s Naka Ward, about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. Her first daughter, Shigeko, was just six months old at the time and died in the bombing’s aftermath. “The atomic bombing was unforgivable, but it couldn’t be avoided,” Ms. Fujioka said. “It was the result of the policies of the United States and Japan.”

Her father had immigrated to Hawaii, where he was working as a tailor. He wanted his daughter to be educated in Japan, so after she graduated from junior high school in Hawaii, in March 1937, she traveled to Japan. The voyage, on the passenger ship Taiyomaru, took two weeks. In Hiroshima, she enrolled as a second-year student at Yasuda Girls’ High School, and continued there through higher grades.

When she was living in Hawaii, she attended a Japanese school in addition to the local school, so she didn’t have any difficulty communicating in Japanese. “I was surprised, though, that boys and girls weren’t allowed to play together,” she said.

After finishing school, she got married in November 1941. She was 19. She tried sending a wedding photo to her father in Hawaii, but the ship carrying the photo was attacked by the United States and sank, so the picture could not be delivered.

Her father was far away when the atomic bomb was dropped. At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, Ms. Fujioka was at home in Sendamachi with her son, her daughter, and her mother-in-law, as well as her sister-in-law, brother-in-law, and niece. They were having breakfast while little Shigeko was asleep in a rattan bed in the garden. Her husband had already left home to work at a military supply depot (the building now houses the Hiroshima City Museum of History and Traditional Crafts), located in the Ujina district.

When the atomic bomb exploded, there was a flash, like lightning, and the ceiling of their house caved in. Another niece had been on her way to school, but she hurried home and all eight family members fled. Just after they crossed the Minami Bridge, which links the districts of Senda and Yoshijima, the bridge caught fire and collapsed.

The night of the bombing, they stayed at the airport in Yoshijima. The next day, they went on foot, crossing three rivers, to reach Ms. Fujioka’s paternal grandparents’ house in Furue, part of present-day Nishi Ward.

On September 7, about one month after the atomic bombing, amid the chaos of the post-war period, Ms. Fujioka’s daughter Shigeko died after vomiting a large amount of milk. With no doctors available, she hadn’t even been aware that her daughter was in poor health. “I don’t have a photo of Shigeko, or a piece of clothing, nothing,” she said in a choked voice.

After the war, while raising her children and managing the household, she took lessons in the Japanese tea ceremony. She then went on to teach tea ceremony lessons until this past March. Making use of her English ability, she also organized tea ceremony lessons for the international community in Hiroshima. She has traveled to the United States, Germany, France, China, and other countries to take part in international exchange through the tea ceremony. Ms. Fujioka urges young people to “Stamp out prejudice and make friends with the people of all nations.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

70% of Japanese immigrants were from Hiroshima and Yamaguchi prefectures

Japanese immigration to the Hawaiian Islands began in the year 1885. An agreement between the Japanese government and the King of Hawaii led to immigrants from Japan working in Hawaiian sugarcane fields.

Both Hiroshima and Yamaguchi prefectures promoted the move by their residents. Because of a rising population along coastal areas, and an economic depression, people believed that working in Hawaii would enable them to bring money back to Japan and live a more affluent life. Hiroshima and Yamaguchi prefectures already had a history of residents heading elsewhere to earn a living, so a wave of immigration to Hawaii now took place.

From 1885 to 1894, the Japanese encouraged immigration, and about 29,000 people left Japan. Of this number, 38%, the largest percentage, were from Hiroshima Prefecture; right behind was Yamaguchi Prefecture, at 36%.

Immigration from Japan to the United States continued until 1924, when it then became forbidden. In 1920, more than 40% of the Hawaii’s entire population, around 256,000 people, were Japanese.

When World War II broke out, the Japanese immigrants in Hawaii, among them teachers and journalists, were detained in internment camps. The sons of immigrants were assembled into units to fight on the front lines in Europe.

Teenagers' Impressions

Her words “Stamp out prejudice” left a strong impression

Ms. Fujioka told us, “Stamp out prejudice and make friends with the people of all nations.”

She has overcome the hardships brought about by the atomic bombing and, since the war ended, has made use of her tea ceremony expertise to travel to many countries. I was moved by the life she has led, an active woman who has pursued her work around the world. Her story is powerful and I’d like to be like her. (Rena Sasaki, 15)

Building a world where families are always together

When the war broke out, she became separated from her father, who was still in the United States, Japan’s enemy. Ms. Fujioka loved her father, though, and was worried about him the whole time.

In Japanese politics today, we see so much squabbling between political parties and within the parties themselves. More important than these quarrels, though, is making the effort to build a world where families can be together, never separated by war. (Arata Kono, 14)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

When Ms. Fujioka lived in Hawaii, she was known as “Gloria.” In fact, she didn’t want to come to Japan, but her father insisted. At the time, it was a sign of success for immigrants to Hawaii when they were able to send their children back to Japan to be educated.

During the war, the son of her father’s second wife joined a military unit composed of sons of immigrants, so her father wasn’t sent to an internment camp. As a result, Ms. Fujioka was able to continue exchanging letters with him.

Because she grew up in Hawaii, she didn’t know much about traditional customs in Japan, like the wife living with the husband’s family. She didn’t even know how to cook rice in a pot, she said. With the different cultural background she gained in Hawaii, she experienced some difficulties becoming accustomed to life in Japan.

Hoping to write a book about her life for her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, she decided to share her experience of the atomic bombing for this article to begin organizing her thoughts. She enjoys her ties with her three children, six grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren, who always receive a card from her on their birthdays. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on July 10, 2012)

Daughter’s death at six months leaves brief memories

Sayoko Fujioka (nee, Morikubo), 89, was born and raised in the United States, in Hawaii. At the age of 14, she moved to Hiroshima, her father’s hometown. She was 22 when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. She experienced the bombing in the Sendamachi district, part of today’s Naka Ward, about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. Her first daughter, Shigeko, was just six months old at the time and died in the bombing’s aftermath. “The atomic bombing was unforgivable, but it couldn’t be avoided,” Ms. Fujioka said. “It was the result of the policies of the United States and Japan.”

Her father had immigrated to Hawaii, where he was working as a tailor. He wanted his daughter to be educated in Japan, so after she graduated from junior high school in Hawaii, in March 1937, she traveled to Japan. The voyage, on the passenger ship Taiyomaru, took two weeks. In Hiroshima, she enrolled as a second-year student at Yasuda Girls’ High School, and continued there through higher grades.

When she was living in Hawaii, she attended a Japanese school in addition to the local school, so she didn’t have any difficulty communicating in Japanese. “I was surprised, though, that boys and girls weren’t allowed to play together,” she said.

After finishing school, she got married in November 1941. She was 19. She tried sending a wedding photo to her father in Hawaii, but the ship carrying the photo was attacked by the United States and sank, so the picture could not be delivered.

Her father was far away when the atomic bomb was dropped. At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, Ms. Fujioka was at home in Sendamachi with her son, her daughter, and her mother-in-law, as well as her sister-in-law, brother-in-law, and niece. They were having breakfast while little Shigeko was asleep in a rattan bed in the garden. Her husband had already left home to work at a military supply depot (the building now houses the Hiroshima City Museum of History and Traditional Crafts), located in the Ujina district.

When the atomic bomb exploded, there was a flash, like lightning, and the ceiling of their house caved in. Another niece had been on her way to school, but she hurried home and all eight family members fled. Just after they crossed the Minami Bridge, which links the districts of Senda and Yoshijima, the bridge caught fire and collapsed.

The night of the bombing, they stayed at the airport in Yoshijima. The next day, they went on foot, crossing three rivers, to reach Ms. Fujioka’s paternal grandparents’ house in Furue, part of present-day Nishi Ward.

On September 7, about one month after the atomic bombing, amid the chaos of the post-war period, Ms. Fujioka’s daughter Shigeko died after vomiting a large amount of milk. With no doctors available, she hadn’t even been aware that her daughter was in poor health. “I don’t have a photo of Shigeko, or a piece of clothing, nothing,” she said in a choked voice.

After the war, while raising her children and managing the household, she took lessons in the Japanese tea ceremony. She then went on to teach tea ceremony lessons until this past March. Making use of her English ability, she also organized tea ceremony lessons for the international community in Hiroshima. She has traveled to the United States, Germany, France, China, and other countries to take part in international exchange through the tea ceremony. Ms. Fujioka urges young people to “Stamp out prejudice and make friends with the people of all nations.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight: Japanese immigrants to Hawaii

70% of Japanese immigrants were from Hiroshima and Yamaguchi prefectures

Japanese immigration to the Hawaiian Islands began in the year 1885. An agreement between the Japanese government and the King of Hawaii led to immigrants from Japan working in Hawaiian sugarcane fields.

Both Hiroshima and Yamaguchi prefectures promoted the move by their residents. Because of a rising population along coastal areas, and an economic depression, people believed that working in Hawaii would enable them to bring money back to Japan and live a more affluent life. Hiroshima and Yamaguchi prefectures already had a history of residents heading elsewhere to earn a living, so a wave of immigration to Hawaii now took place.

From 1885 to 1894, the Japanese encouraged immigration, and about 29,000 people left Japan. Of this number, 38%, the largest percentage, were from Hiroshima Prefecture; right behind was Yamaguchi Prefecture, at 36%.

Immigration from Japan to the United States continued until 1924, when it then became forbidden. In 1920, more than 40% of the Hawaii’s entire population, around 256,000 people, were Japanese.

When World War II broke out, the Japanese immigrants in Hawaii, among them teachers and journalists, were detained in internment camps. The sons of immigrants were assembled into units to fight on the front lines in Europe.

Teenagers' Impressions

Her words “Stamp out prejudice” left a strong impression

Ms. Fujioka told us, “Stamp out prejudice and make friends with the people of all nations.”

She has overcome the hardships brought about by the atomic bombing and, since the war ended, has made use of her tea ceremony expertise to travel to many countries. I was moved by the life she has led, an active woman who has pursued her work around the world. Her story is powerful and I’d like to be like her. (Rena Sasaki, 15)

Building a world where families are always together

When the war broke out, she became separated from her father, who was still in the United States, Japan’s enemy. Ms. Fujioka loved her father, though, and was worried about him the whole time.

In Japanese politics today, we see so much squabbling between political parties and within the parties themselves. More important than these quarrels, though, is making the effort to build a world where families can be together, never separated by war. (Arata Kono, 14)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

When Ms. Fujioka lived in Hawaii, she was known as “Gloria.” In fact, she didn’t want to come to Japan, but her father insisted. At the time, it was a sign of success for immigrants to Hawaii when they were able to send their children back to Japan to be educated.

During the war, the son of her father’s second wife joined a military unit composed of sons of immigrants, so her father wasn’t sent to an internment camp. As a result, Ms. Fujioka was able to continue exchanging letters with him.

Because she grew up in Hawaii, she didn’t know much about traditional customs in Japan, like the wife living with the husband’s family. She didn’t even know how to cook rice in a pot, she said. With the different cultural background she gained in Hawaii, she experienced some difficulties becoming accustomed to life in Japan.

Hoping to write a book about her life for her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, she decided to share her experience of the atomic bombing for this article to begin organizing her thoughts. She enjoys her ties with her three children, six grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren, who always receive a card from her on their birthdays. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on July 10, 2012)