Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 3)

Apr. 16, 2012

Paper printed by other companies

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Braving fierce flames, made his way through city of dead bodies

Appealing for help from other newspaper companies via military radio

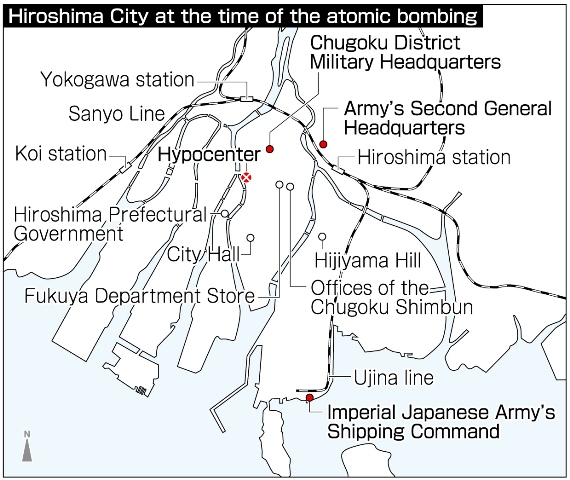

The offices of the Chugoku Shimbun in Kami-nagarekawa-cho (now Ebisu-cho, Naka Ward) were destroyed by fire as a result of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima by the United States military on August 6, 1945. The paper’s two rotary presses also burned, and the ability to communicate with the outside was lost. Publication of the paper was dealt a crippling blow. The surviving employees strove to resume publication under unprecedented conditions. When and how were papers delivered to the destroyed city? How was the devastation covered? In this article the Chugoku Shimbun looks into wartime reporting on the atomic bombing.

Three days after destruction

Papers delivered

On the morning of August 6, Haruo Oshita, then 42, looked up and saw a column of black smoke rising into the sky above Hiroshima as he headed from his home in Itsukaichi (now part of Saeki Ward) to the offices of the Chugoku Shimbun. He had just taken over as page editor in charge of writing headlines for news articles.

Along the Miyajima Highway Mr. Oshita caught a ride on a relief truck from the Hatsukaichi Police Department, but the bridge into the Hiroshima delta had collapsed and the truck could not get into the city. He ran into Rihei Numata, then 43, head of the paper’s Itsukushima bureau, and several others, and they crossed the Koi Railway Bridge (about 2.3 km from the hypocenter). The railroad ties on the bridge were on fire.

With raging flames blocking their path, they proceeded down Aioi Street. “There was nothing but dead bodies,” Mr. Oshita said. “I finally made it to the office a little after 2 p.m. The presses were on fire, and the newsprint warehouse was in flames too.” He simply sat there, dumbfounded, he said.

Shigetoshi Itokawa, then 40, manager of the Research Department, and others rushed to the newspaper offices. “It must have been around 4:30 in the afternoon,” he said.

Jitsuichi Yamamoto, then 55, president of the Chugoku Shimbun, had evacuated to Fuchu-cho. Mr. Oshita learned what to do from Mr. Itokawa, who had already discussed the matter with the president. “Ask another company to put out our paper,” he was told. Telephone and telegraph service was disrupted. “If the military radio network is undamaged, use that,” Mr. Yamamoto had said. It was decided to ask for help from the Osaka and western Japan offices of the Asahi and Mainichi newspapers. The Chugoku Shimbun had been contracted to print the two papers in Hiroshima Prefecture and published pages under the mastheads of both.

Reporters’ mission: Keep public calm

Mr. Itokawa, Mr. Numata and another man headed for the Imperial Japanese Army’s Shipping Command in Ujina (Minami Ward) while Mr. Oshita and another man set out for the Army’s Second General Headquarters in Futaba no Sato (now part of Higashi Ward), “trudging wearily along.”

Mr. Oshita’s son Yuji, 75, recalled, “More than a week had gone by when a young employee came to our home and said, ‘Your father is working out of the president’s home in Fuchu-cho, so put your mind at ease.’” Mr. Oshita said his father never told him the details of what happened on the day of the bombing.

Haruo Oshita wrote a description of the devastation of Hiroshima and a detailed account of the actions of reporters titled “The End of History,” which was included in “Hiroku Dai Toa Senshi” (Secret Records of the Greater East Asia War), a 12-volume history published by Fuji Shoen of Tokyo in 1953, the year after the end of the Allied Occupation of Japan.

The mission of reporters during the war emerges from Mr. Oshita’s account. He described the idea behind the effort to restart publication of the paper amid those unprecedented circumstances. “We were in the middle of a war. In order to keep the public calm and to achieve unity of public opinion, it was essential that we put out a paper every day.”

Haruko, the wife of Mr. Itokawa, who headed for Ujina after the A-bombing, turned 100 years old in March. While her husband was working in Tokyo, she also experienced the February 26 incident (an attempted coup d’état by the military in 1936) and the March 1945 air raid on Tokyo.

In a firm tone of voice she searched her memories. “Itokawa came home late that night and said, ‘I used the communication network of the Akatsuki Shipping Transport Unit.’” At the time they were living in Ushita (Higashi Ward).

“Overview of Measures Taken in Hiroshima Immediately after the Aerial Bombing” consists of records made by Hiroshima Prefecture starting August 6 and is housed in the city’s archives. In addition to descriptions of the disposal of bodies, the establishment of aid stations and the distribution of rations, it also includes a reference to the Chugoku Shimbun in the August 7 entry: “The Chugoku Shimbun has said it will deliver 100,000 copies from Osaka, 150,000 copies from Moji and 12,000 copies from Matsue. The papers are expected to arrive tomorrow, August 8.”

In “Eighty Years’ History of the Chugoku Shimbun” published in 1972, it is recorded that “a request via radio” was made “to the Osaka and western Japan offices of the Asahi and Mainichi newspapers via both the Kinki and Kyushu Regional Superintendencies-general.” These were also the first reports by Chugoku Shimbun reporters on the devastation of Hiroshima. The papers from Matsue were printed by the Shimane Shimbun (now the Sanin Chuo Shimbun). Starting August 11, 10,000 copies of the Shimane Shimbun bearing the masthead of the Chugoku Shimbun as well were “delivered to readers in the Hiba and Futami areas of Hiroshima Prefecture,” according to the section on the Shimane Shimbun in “100 Years of Japanese Newspaper History” published in 1960.

Inability to report what they saw

The papers that were put out by other companies in response to the request made via military radio by the reporters who walked through the city of dead bodies were delivered starting with the edition of August 9, three days after the A-bombing.

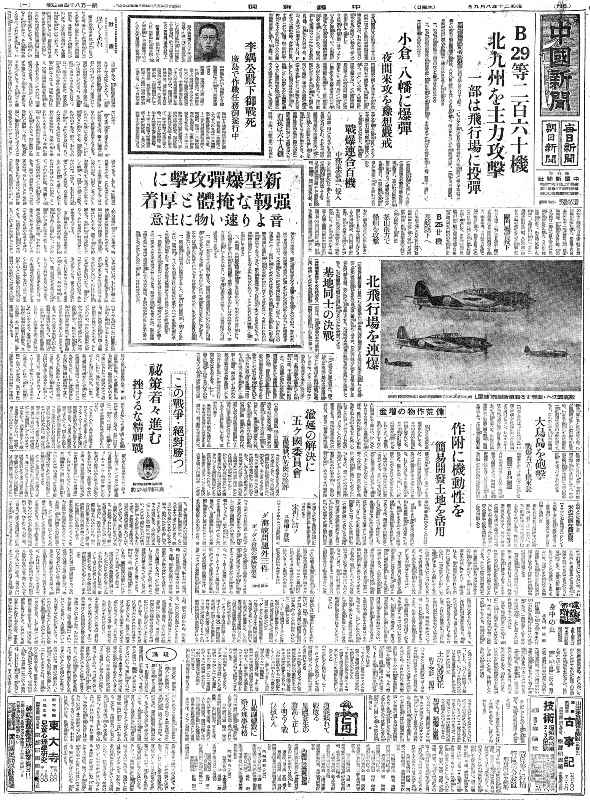

The front page of that edition featured a report on the air raids on northern Kyushu and Nagasaki, which had been announced by the Western Military District. To the left of that story was an article on the death in the A-bombing of Yi Wu, a member of the imperial family of Korea and a staff officer attached to the Second General Headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army. His death had been announced by the Ministry of the Imperial Household on August 8. An announcement by the Ministry of the Interior’s Air Defense General Headquarters was printed under a headline referring to an “attack with a new type of bomb.” “Underground shelters should be dug as deeply as possible,” it said.

Where was this copy of the paper that was delivered to Hiroshima just after the bombing printed? Upon checking with the western Japan offices of both the Asahi and Mainichi newspapers, it was found to be an early edition printed at the western Japan offices of the Mainichi Shimbun in Moji (now part of Kitakyushu).

The late edition carried an article saying that a “high-performance air burst bomb” had been dropped on Hiroshima “around 8:10 on August 6.” The report noted that “there was extensive damage, but the fire had mostly died down by evening.” An edition printed at the western Japan offices of the Asahi Shimbun reported the dropping of a “high-performance tracer bomb.” Both of these reports were announced by the Chugoku District Military Headquarters at “12 o’clock on the 7th.”

This is earlier than the announcement made by the Headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army, which made this announcement at 3:30 p.m. on August 7: “1. Yesterday, August 6, Hiroshima sustained heavy damage as the result of an attack by a small number of enemy B-29 aircraft. 2. The enemy apparently used a new type of bomb in the aforementioned attack. The details are currently under investigation.”

The bombing was the top story on the front page of every newspaper’s August 8 edition, but even if they were aware that it had been an atomic bomb, they could not say so.

The Cabinet Intelligence Bureau obtained and circulated a recording of the broadcast by U.S. President Harry Truman made 16 hours after the bombing (in the pre-dawn hours of August 7) in which he stated that an atomic bomb had been dropped. The Kure Naval Station had already dispatched a survey team at 5:30 p.m. on August 6.

At a meeting of the Joint Army-Navy Study Group in Hiroshima on August 10, the Imperial General Headquarters survey team that physicist Yoshio Nishina had accompanied “confirmed that it was an atomic bomb,” according to a draft of the survey team’s report held by the Peace Memorial Museum.

But, out of concern for the effect it would have on the morale of the population, the military opposed announcing that it had been an atomic bomb. The government as well referred to it as a “new type of bomb,” according to “Shusenki,” written in 1948 by Kainan Shimomura, who had been president of the Cabinet Information Board.

The fact that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima was first reported in the August 16 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun. This edition, which also included the Imperial rescript announcing the end of the war, was printed at the western Japan offices of the Asahi Shimbun. Reporters from various newspapers began arriving in Hiroshima on August 7 from Osaka, Yamaguchi and other areas, but because of controls on news reports, they could not provide accurate descriptions of the devastation they saw.

From the day of the A-bombing most of the surviving employees of the Chugoku Shimbun and their families were faced with the deaths of family members. They were also struggling to learn whether others were safe.

Mr. Yamamoto, company president, did not know the whereabouts of his son Toru, then 29. Toru, who was the paper’s managing editor, had been drafted a second time in March and was assigned to the news team of the Hiroshima Divisional Headquarters. His wife Yuriko, now 91, who was pregnant at the time, walked the city for days in search of him. His body was never found.

Believed to be a duty: Recovery of the company

Yasuo Yamamoto, then 42, manager of the paper’s stenographic department, was bicycling to work from his home in Danbaranaka-machi (now Danbaraminami, Minami Ward) when he was blown about by the blast from the A-bombing. His son, Masumi, then 13, a first-year student at Hiroshima No. 1 Junior High School, had been mobilized for the demolition of buildings and was working near city hall at the time of the bombing. He returned home with “his face swollen by burns.”

“It was around 11 that night. ‘Is there really a Pure Land?’ My son asked this strange question, breathing faintly… ‘Is there jellied bean paste there?’ My wife finally choked out an answer. ‘Yes, there’s jellied bean paste and everything there.’ Then he said, ‘Then I think I’ll die.’” This account was included in “The Stars Are Watching,” published by the Association of Bereaved Families of Students of Hiroshima No. 1 Junior High School in 1954.

Mr. Yamamoto put his son’s body in a handcart and carried it to the crematorium. The following day, August 8, he went to work.

At the deserted entrance to the newspaper’s offices, he ran into an executive who asked him to go to Nukushina (now part of Higashi Ward), where one rotary press had been taken for safekeeping. He described his feelings at that time in the August 1965 edition of “Shinju,” an anthology of poetry he edited.

“My son was dead, and I should have had no human will, but from that moment on I believed that the recovery of the Chugoku Shimbun was a duty, and I began to rouse myself.” After the publication of the paper by other companies, the Chugoku Shimbun’s effort to print its own paper began amid unprecedented chaos.

(Originally published on April 7, 2012)

Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 4)