Moment of silence observed under blue skies of Hiroshima: Connection with past sensed

Sep. 16, 2011

An interview with Yuichi Seirai, author: Questions from Nagasaki

by Masami Nishimoto, Editor and Senior Staff Writer

The atomic bombing and the martyrdom of its Christians underlie the history of Nagasaki. Author Yuichi Seirai, 52, depicts the intimate details of the lives of the city’s people, who carry the burden of this history, in richly poetic language. He has received several prizes for his works, which link the present with the past, including the Akutagawa Prize and the Junichiro Tanizaki Prize. Seirai, whose real name is Akitoshi Nakamura, is the son of survivors of the atomic bombing. An employee of the City of Nagasaki, since November of last year he has served as director of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum. The Chugoku Shimbun asked him why he writes about the atomic bombing and how he feels as an author about the developments that have taken place since the March 11 accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, which has forced a reassessment of the relationship between human beings and the atom. The following are excerpts from that interview.

Native of Nagasaki: Imagination stirred by local memories

I don’t write fiction about the atomic bombing just because I’m the son of survivors. I do it because the memories in Nagasaki stir my imagination. The story of the atomic bombing was familiar to me because it concerned my family and the local area.

I was born in the City of Nagasaki, and both of my parents were survivors of the atomic bombing. My father, who died of lung cancer two years ago, didn’t talk about the atomic bombing much, but my mother did. She talked about how her hair fell out and her gums bled. We haven’t talked about it to people outside our family, but my grandfather on my father’s side experienced both of the atomic bombings. While working at the Nagasaki shipyard [of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries] he was sent to Hiroshima to help out [just after the shipyard in Eba opened]. He experienced the atomic bombing there, and then came back to Nagasaki, where he experienced that A-bombing also.

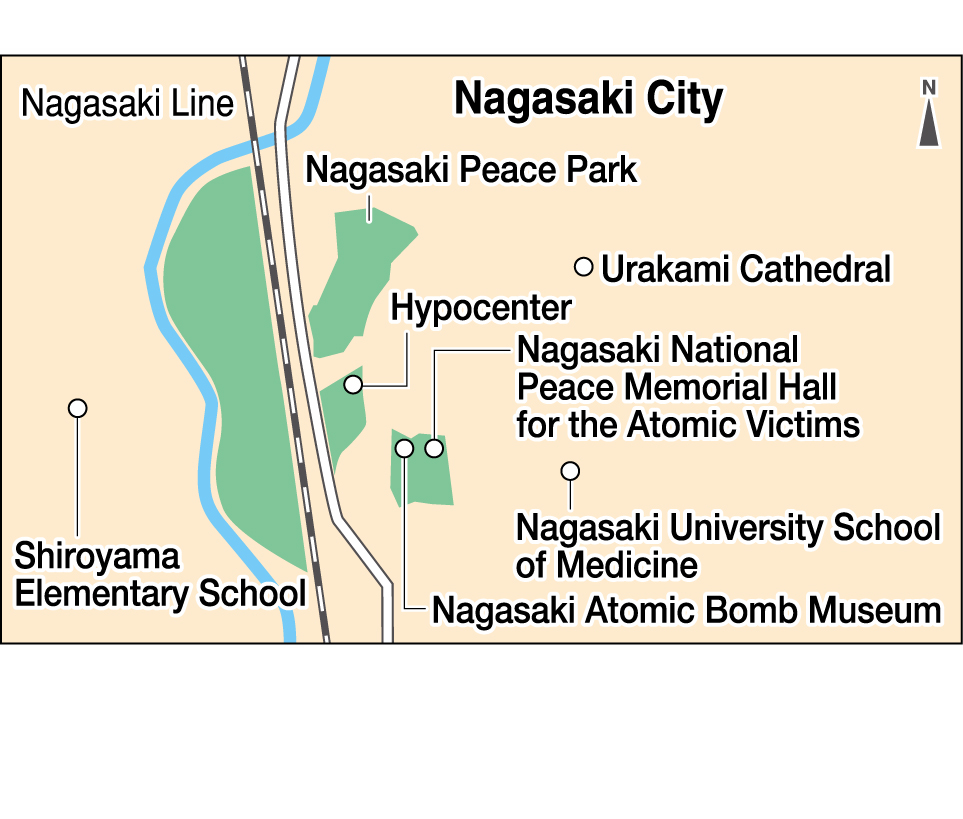

We were living in the Goto Islands because my father, who worked for the prefectural government, had been transferred there. We moved back to Nagasaki, and I entered Shiroyama Elementary School, where many children had died in the atomic bombing. The school holds a peace memorial ceremony on the ninth of every month. The monument to Kayoko was erected when I was in the third grade. I remember we all lined up in the schoolyard to hear her mother speak.

Shiroyama Elementary School is about 500 meters from the hypocenter. About 1,400 students of the school and another 105 mobilized students died there. Kayoko Hayashi was a 15-year-old mobilized student at the time of the bombing. In 1949 her mother Tsue planted cherry trees at the school in memory of Kayoko. They are referred to as “Kayoko’s cherry trees.” The ceremony at the school was first held in 1951 and is held to this day. Three years ago a citizens’ group began sending seedlings from the trees all over the country. One was planted at Toyohira Minami Elementary School in Kita Hiroshima in Hiroshima Prefecture.

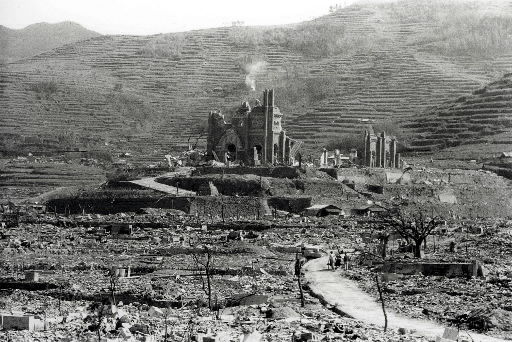

The house we lived in then was near Matsuyama-cho, the hypocenter of the bombing. I was shocked when I went to the public bath and saw people who still had keloid scars. I used to play at the nearby Urakami River in the summer, and I was often told that many people had died there.

Although the atomic bombing happened long before I was born, the fact that the atomic bomb had been dropped on August 9 and the area had been devastated became part of my own memory. I was also exposed to Nagasaki’s Catholic history at Shiroyama Elementary. One day some kids who were playing with me boasted that they had baptismal names. I was shocked and wondered why they had other names. You can say that I grew up with a sense of the meaning of having been born in Nagasaki, and in some ways I am still affected by my childhood experiences.

Time needed to find words to describe the A-bombing: Feelings warped even now

Starting in the 1950s the news media referred to the two cities using expressions such as “angry Hiroshima” and “prayerful Nagasaki.” In 1962 the American magazine Time ran an article titled “Japan: Tale of Two Cities” in which it said, “Hiroshima today is grimly obsessed by that long-ago mushroom cloud; Nagasaki lives resolutely in the present.” Are there differences in the stories of the two cities?

It was many years until Nagasaki’s experience was recounted by writers like Kyoko Hayashi [“Matsuri no ba” (Ritual of Death), 1975, winner of the Akutagawa Prize], who herself was an atomic bomb survivor, and Hiroshi Takeyama [winner of the Saito Mokichi Tanka Literary Prize in 2002; died in 2010]. In Hiroshima Tamiki Hara, Yoko Ota and others wrote extensively about the bombing not long after it occurred. In that way Hiroshima and Nagasaki differ.

In Nagasaki many people had questions about the atomic bombing: What was it all about? What should we make of it? Is it OK to go on living? It took them time to put their feelings into words, and I think their feelings are warped even now. In terms of expression, perhaps it may be said that Nagasaki expresses itself in a more nuanced fashion than Hiroshima.

The image of “prayerful Nagasaki” is in part because it is a Catholic city. Takashi Nagai also had a lot to do with that image. Dr. Nagai specialized in radiology, so his descriptions of the city after the bombing are scientific. At the same time, because he was a Catholic, he had a theological view as to how we should accept the atomic bombing. This is expressed in his well-known book “The Bells of Nagasaki.”

Takashi Nagai [1908-1951] was born in Matsue [Shimane Prefecture] and went to Nagasaki Medical College. He was baptized while boarding at a home in Urakami. He was an assistant professor at the time of the atomic bombing and worked hard to provide aid to the victims immediately after the bombing. He wrote “The Bells of Nagasaki” and other works on his sickbed and was the first person to be named an distinguished citizen of Nagasaki.

In a tribute that he read at a combined funeral mass for the victims in Urakami [in November 1945], Dr. Nagai referred to Nagasaki as “the chosen victim, the lamb without blemish slain as a whole burnt offering on the altar of sacrifice.” Referred to as the “Urakami ‘hansai’ (burnt offering) theory,” this later became the subject of intense debate. The persecution of Christians had been overcome and the cathedral had finally been built. Then the atomic bomb was dropped. How could people accept this? Ordinary people as well were confronted with a sort of ideological concept. I think that became the major trend in Nagasaki.

My family is not Catholic, but in her later years my grandmother told of finding a gold cross while digging in a field in [her hometown of] Shimabara. In fact it was a dream, but it stuck with me. I believed that we were human beings who had lived our lives having forgotten God. My imagination was stimulated, and I used that idea as the theme of my first book.

“Ground Zero,” which I began writing 60 years after the atomic bombing, depicts memories, albeit faint, that come back to me at certain times. The characters talk about how they lived after the atomic bombing and have internal dialogues with themselves about why they met with such suffering. This is because local memories come into my mind.

The atomic bombing is an intense non-fiction story. Depictions of those scenes by people who did not experience the bombing lack realism and stray from reality. While writing “Ground Zero” I met Kyoko Hayashi, and she told me it was all right to write freely. I decided I should stretch my imagination.

Hiroshima’s stance on the atomic bombing is clear, and its political activities and message are strong. It was the first city to be A-bombed and became known throughout the world. I think its message is also easily understood by people who come from outside the city.

Only two cities have suffered atomic bombings: Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Even if Hiroshima can only describe being the victim of the first bombing, I think Nagasaki’s story is included in that. There is no need to compete with each other. I accompanied the late Mayor Itcho Ito to the peace memorial ceremony in Hiroshima in 2005. The broad reaches of the blue sky seemed to envelop those in attendance as they observed a moment of silence. I felt that blue sky was somehow connected with the sky over Nagasaki at the moment the atomic bomb was dropped.

The world after Fukushima: New experience: Turning point for civilization

At the peace memorial ceremony on August 9 Mayor Tomihisa Taue said, “It is necessary to promote the development of renewable energies in place of nuclear power.” The director of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum participates in the drafting of the Peace Declaration along with the Peace Promotion Section, which puts together the final draft, and the Atomic Bomb Heritage Section, which is in charge of peace education.

Since 1980 Nagasaki’s peace declaration has been drafted by a committee consisting of atomic bomb survivors, academic experts and others that is chaired by the mayor. The mayor’s ideas are also clearly reflected in the declaration.

As was reported in the news media, this year’s declaration emerged after heated debate about the content in light of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant. As a city employee — not as an author — I have the job of putting the documents together. And my thoughts as a writer should not enter into the matter. There is a clear division there.

As far as managing the museum, we must properly preserve the materials related to the atomic bombing and endeavor to enhance our exhibits. The citizens are also bearing a financial burden. It’s the same in Hiroshima. The central government must do more about the war overall, I think.

In late July [Nagasaki native] Takashi Tachibana gave a lecture at the museum in which he said, “We must record people’s memories of the war.” I could relate to this sentiment.

Since 2008 the National Council of Japan Nuclear-Free Local Authorities, of which Mayor Taue is chairman, has been conducting a “Parent-Child Reporters” program. Under this program elementary school students from outside Nagasaki Prefecture and their parents interview atomic bomb survivors and report on the peace memorial ceremony. People who work overseas are accredited as “peace correspondents” for the city. Yoko Ono, who recently visited Nagasaki, became one of our peace correspondents. I also help with other activities such as one in which the private sector sends high school students who serve as “peace ambassadors” to the United Nations Office at Geneva.

Membership in Mayors for Peace, of which the mayor of Hiroshima serves as president and the mayor of Nagasaki serves as vice president, has grown thanks in large part to the cooperation of non-governmental organizations. [Membership currently consists of the mayors of 4,892 cities in 151 countries and regions.] The message is spread by making use of personal connections and networking. The days in which only government took on this task are gone.

Talking about the post-March 11 era as an author, I think human beings are faced with new experiences and we are at a turning point for civilization. How far should science, including cloning technology from the life sciences, be allowed to progress? I think people realize the danger in the notion that science is almighty. Interest in religious ideas of acceptance and religious viewpoints may grow.

Nuclear weapons and nuclear power are problems of history that human beings created. When I was a boy no one thought the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union would ever end. But the challenge was overcome. It was the same with slavery in the U.S., which had existed for many years. Human beings overcome history and face new challenges.

There are issues that will take time to resolve. I would like young people to keep these issues in the backs of their minds and not be distracted by short-term gain. After I graduated from college I was at loose ends for nearly two years, so I can understand the anxiety the young generation today feels about their lives. But it is important to consider what the results of your actions will be 100 years from now. That also shapes people’s individuality.

I think the problem of the atom is one that will have to be considered as long as human beings live.

Yuichi Seirai

Born in Nagasaki in 1958. Graduate of Nagasaki University. Received the Bungakukai Prize for New Writers for “Jeronimo no Jujika” (Geronimo’s Cross) in 1995, the Akutagawa Prize for “Seisui” (Holy Water) in 2001, and the Tanizaki Junichiro Prize and Ito Sei Literary Prize for “Bakushin” (Ground Zero) in 2007. Other works include “Terenparen.” Became a city employee in 1983 and manager of the city’s Peace Promotion Section in 2005. Named director of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum in 2010.

(Originally published on August 22, 2011)