My Life: Interview with former Hiroshima Mayor Takashi Hiraoka, Part 10

Oct. 22, 2009

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

A Korean A-bomb survivor smuggled himself into Japan to seek medical treatment in 1970. This incident led to a lawsuit over A-bomb disease certification.

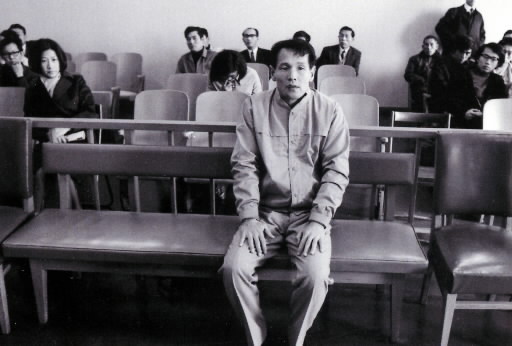

I happened to read a newspaper article on December 8, 1970, about Son Jin Doo, then 43, who left Busan, South Korea, and illegally entered Saga Prefecture, where he was arrested. I went to Karatsu Police Station with Masahiko Shigeta, a freelance photographer based in Hiroshima, and some other friends who were concerned about the incident. We managed to gain permission to see him and took some photographs. To verify his account, we carried the photos with us and started to gather information around Minami Kanon [Nishi Ward, Hiroshima] where Mr. Son allegedly lived at the time of the atomic bombing. I asked some students at Hiroshima University for help. They were involved in the struggle over university reform and other political issues. Some young doctors went to examine Mr. Son and the students organized a citizens' group to support him. They demanded that he be released on bail and given medical treatment in Hiroshima.

Mr. Son was sentenced to ten months in prison for violating the Immigration Control Order in 1971. While he was serving time at a prison in Fukuoka Prefecture, his condition deteriorated. On his behalf, his supporters filed an application for the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate. The certification system had begun in 1957, but Hiroshima Prefecture rejected the application in line with the policy of the then Ministry of Health and Welfare. In 1972 a lawsuit was filed demanding the prefecture's decision be reversed.

We asked Tatsumi Nakajima, a journalist and a friend of mine [who died in 2008], to help with our activities in Tokyo. Through the students, we contacted Rui Ito, who lived in Fukuoka, and asked for support concerning the lawsuit. [Rui Ito was the fourth daughter of Sakae Osugi and died in 1996]. I raised funds for legal fees and the travel expenses for supporters.

I was the associate editor at the time. I couldn't openly lead the support activities. I believed, as a journalist, that I should be independent and fair. If senior editors were engaged in a particular movement, it would bring trouble to the company. But I kept asking myself: "Why were Korean people exposed to the atomic bomb? Who is responsible for this?" [Mr. Hiraoka wrote "Fighting Indifference" for the August 1974 issue of the magazine "Sekai" ("World").] I was involved in the activities as an individual out of my own belief. If I had abused my authority and made front-line reporters cover the issue, I would have been personalizing the issue at the newspaper. I didn't do that.

In 1978, the Supreme Court upheld the decisions made by lower courts that ruled Mr. Son was entitled to receive the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate, noting "The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law is based on consideration of national reparations." This court case paved the way for survivors living abroad to obtain certification. It eventually served as a basis for the enforcement of the Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Support Law in 1995.

I thought we could establish that the national government is responsible for the suffering of atomic bomb survivors if we put up a sensible fight in court. But the 1970s was a time of radical thinking. Those involved in the aggressive student movement and the critics that sympathized with them denounced our approach to fighting the government on its own turf. But we persevered and won. Through the court battle, for which Mr. Son was the plaintiff, Japan's pacifism was strengthened.

(Originally published on October 15, 2009)

Supporting the lawsuit over A-bomb disease certification

A Korean A-bomb survivor smuggled himself into Japan to seek medical treatment in 1970. This incident led to a lawsuit over A-bomb disease certification.

I happened to read a newspaper article on December 8, 1970, about Son Jin Doo, then 43, who left Busan, South Korea, and illegally entered Saga Prefecture, where he was arrested. I went to Karatsu Police Station with Masahiko Shigeta, a freelance photographer based in Hiroshima, and some other friends who were concerned about the incident. We managed to gain permission to see him and took some photographs. To verify his account, we carried the photos with us and started to gather information around Minami Kanon [Nishi Ward, Hiroshima] where Mr. Son allegedly lived at the time of the atomic bombing. I asked some students at Hiroshima University for help. They were involved in the struggle over university reform and other political issues. Some young doctors went to examine Mr. Son and the students organized a citizens' group to support him. They demanded that he be released on bail and given medical treatment in Hiroshima.

Mr. Son was sentenced to ten months in prison for violating the Immigration Control Order in 1971. While he was serving time at a prison in Fukuoka Prefecture, his condition deteriorated. On his behalf, his supporters filed an application for the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate. The certification system had begun in 1957, but Hiroshima Prefecture rejected the application in line with the policy of the then Ministry of Health and Welfare. In 1972 a lawsuit was filed demanding the prefecture's decision be reversed.

We asked Tatsumi Nakajima, a journalist and a friend of mine [who died in 2008], to help with our activities in Tokyo. Through the students, we contacted Rui Ito, who lived in Fukuoka, and asked for support concerning the lawsuit. [Rui Ito was the fourth daughter of Sakae Osugi and died in 1996]. I raised funds for legal fees and the travel expenses for supporters.

I was the associate editor at the time. I couldn't openly lead the support activities. I believed, as a journalist, that I should be independent and fair. If senior editors were engaged in a particular movement, it would bring trouble to the company. But I kept asking myself: "Why were Korean people exposed to the atomic bomb? Who is responsible for this?" [Mr. Hiraoka wrote "Fighting Indifference" for the August 1974 issue of the magazine "Sekai" ("World").] I was involved in the activities as an individual out of my own belief. If I had abused my authority and made front-line reporters cover the issue, I would have been personalizing the issue at the newspaper. I didn't do that.

In 1978, the Supreme Court upheld the decisions made by lower courts that ruled Mr. Son was entitled to receive the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate, noting "The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law is based on consideration of national reparations." This court case paved the way for survivors living abroad to obtain certification. It eventually served as a basis for the enforcement of the Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Support Law in 1995.

I thought we could establish that the national government is responsible for the suffering of atomic bomb survivors if we put up a sensible fight in court. But the 1970s was a time of radical thinking. Those involved in the aggressive student movement and the critics that sympathized with them denounced our approach to fighting the government on its own turf. But we persevered and won. Through the court battle, for which Mr. Son was the plaintiff, Japan's pacifism was strengthened.

(Originally published on October 15, 2009)