Former baseball star, an A-bomb survivor of Hiroshima, speaks out for peace

Jan. 29, 2011

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Isao Harimoto, 70, has a Korean name: Jang Hun. Mr. Harimoto is a second-generation Korean-Japanese born in Hiroshima. He is also an A-bomb survivor. Fighting baseless racial discrimination and the fear of the aftereffects of radiation, Mr. Harimoto set a number of professional baseball records, including winning the batting title seven times and producing a total of 3,085 hits. He holds a deep emotional attachment toward his hometown of Hiroshima and strong hopes for the elimination of the world’s nuclear weapons as well as peace on the Korean Peninsula, which remains divided. In this article, the Chugoku Shimbun will relate Mr. Harimoto’s story, which he shared during an interview in Hiroshima.

I heard that my father was encouraged to come to Hiroshima by his younger brother, who had already settled down here. They pulled a two-wheeled cart through the city and sold scrap iron and secondhand items. My father felt he could earn a living that way and so he invited his mother, older brother, and two older sisters to move to Japan. It was the spring of 1939.

I was born in Ozu town, now part of Minami Ward. Near the Higashi Ohashi Bridge, still straddling the Enko River, there was a row house where Korean people lived. From the days of my earliest recollections, I played on the bank of the river. One winter when I was four, out on the bank baking sweet potatoes with my friend, a three-wheeled truck backed up and struck me. I suffered serious burns to my right hand when it was jarred into the fire, and my fourth and fifth fingers became stuck together. The driver fled, and my uncle, unable to stand by idly, appealed to the police. But I heard that they turned him away, telling him, “You’re Korean.”

Mr. Harimoto’s father Jang Sang Jeong came from Changnyeong-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do and his mother Pak Sun Bun from Hapcheon-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do. The number of Korean immigrants to Hiroshima increased from the mid-1920s due to Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910. In 1940, when Mr. Harimoto was born, roughly 38,000 Koreans lived in Hiroshima Prefecture, according to records of Japan’s Home Ministry. In addition, due to the application of the National Conscription Ordinance to those on the Korean Peninsula in 1944, in the wake of the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, a large number of Koreans were exposed to the atomic bombing in Hiroshima.

When the bomb exploded, I was at a row house in Danbara-shinmachi, about 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. There was a flash and an enormous roar. The next thing I knew my mother was shielding me and my sister, three years older, with her body, though her back was covered in blood due to flying shards of glass. We were urged to run, in Korean, and we fled to a vineyard. Even now, 65 years after the bombing, I can still vividly recall the people groaning and the strange stench. There were dozens of people in the vineyard. When I tried to go see people who were screaming for water and jumping into a canal nearby, my mother stopped me.

My eldest sister had been mobilized at a work site at Hijiyama Hill or thereabouts. My older brother and others went to look for her and they carried her back on a stretcher. She was suffering terrible burns, on her face, too. I was shocked to see a human being, the sister I so admired, transformed into such a state. I remember bringing charred grapes to her mouth. I have no idea how many days passed after that, but one day I heard my mother crying and I knew my sister was dead.

The name of Mr. Harimoto’s eldest sister, Jang Jeom Ja, is recorded in the register for the A-bomb victims, housed in the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in Hiroshima. According to the application form, she was exposed to the atomic bombing in Tsurumi town in Naka Ward at the age of 12. Students of the First National School (now, Danbara Junior High School), among others, were mobilized to work all over Tsurumi town, west of Hijiyama Hill, for the war effort, helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. Mr. Harimoto confirmed the record of the death of his eldest sister for the first time on this occasion.

Yes, this must be my eldest sister. I guess my older brother (Seye Ol, who died in 1996 at the age of 64) filed the application, since my mother was unable to write in Japanese. Perhaps because of the cultural differences, my mother did not keep any of her belongings and, until her death, did not talk to us about her. (Mr. Harimoto’s mother died in 1985 at the age of 83.) I’m 70 now and I’ve finally learned where my sister experienced the atomic bombing. I feel grateful for that.

The war was over, but we had no home. For a while we lived under the Higashi Ohashi Bridge with others, including a Korean family. As my father was the eldest son, he went back to South Korea ahead of us. But then he died. My mother, upon hearing that a ship, operating illegally, had capsized off the coast of Shimonoseki in Yamaguchi Prefecture after leaving Hiroshima, gave up returning to South Korea out of concern for our safety. So our family of four began living in a small, rented room in Shinonome town (now, Kami-shinonome in Minami Ward).

From watching other people cook, my mother learned how to make “horumon yaki,” grilling the guts of chickens and other animals that my older brother bought at the black market. She sold unrefined sake, too. She worked so doggedly to provide for us that I hardly saw her sleep.

I was a naughty child from the time I entered Hijiyama Elementary School. It was partly my nature, and I was big physically, too. In summer, I went swimming in the Enko River in only my underwear. I stood up against older students who bullied my Korean friends. In alleys of the Danbara district, I also played “menko,” a game where you throw a thick card at the ground to try to flip over the card of an opponent, as well as “ramune,” a game with marbles.

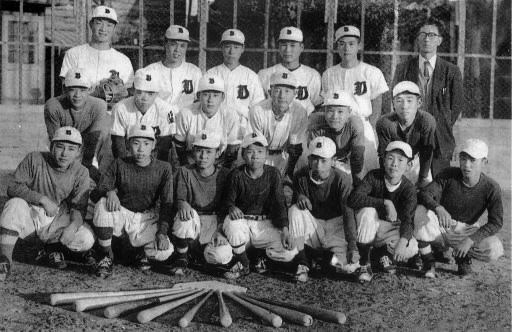

I started playing baseball when I was in the fifth grade at elementary school. An older boy in the neighborhood invited me to play, and I hit a double in my first baseball game. I loved it and I begged him to keep letting me play. Although I had had surgery on my right hand, I still didn’t have complete control over my fingers and so I couldn’t throw the ball so far. But I practiced throwing against a wall and I was able to completely alter myself into a left-handed pitcher and hitter.

Around then, in 1950, the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, the city’s professional baseball team, was established. Tetsuharu Kawakami and Noboru Aota, players I admired, came to the stadium in Minami Kanon (now, the Coca Cola West Hiroshima Stadium in Nishi Ward). As I had no money, I climbed a tree outside the stadium to watch the game. When I peeked into their lodgings, I saw white rice and steaks on the table. I was surprised at their well-heeled life, which led to my wish to become a professional baseball player.

I might have joined a swimming club, though, if there had been a swimming pool at Danbara Junior High School at the time. Whether that was fortunate or not, there wasn’t and so I kept playing baseball. When I entered my third year of junior high school, I hoped to go to Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School and star at the big high school baseball tournament at Koshien Stadium. Kazuyoshi Yamamoto, who went to Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School from Midorimachi Junior High School in Minami Ward and later became a slugger for the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, was two years older than me. He let me take part in the baseball practice at his school. But I failed to get admitted. It was a small thing, but at Danbara Junior High I once hit an older student in a fight with the soccer team over the use of the school ground. Koryo High School also refused me, saying that I was a roughneck.

While working in the cafeteria at Matsumoto Commercial High School (now, Setouchi High School), I attended night school there and continued to play baseball. But I was determined to play at Koshien Stadium. For the second semester, I transferred to Namisho High School (now, Namisho High School at Osaka University of Health and Sport Sciences) in Osaka Prefecture, which had a powerful baseball team. The manager of the baseball team at Matsumoto Commercial High School believed that I could become a good player. My older brother persuaded my mother to let me pursue my dream, telling her, “He won’t amount to much if we leave him where he is.” He then sent me money for my school expenses from his wages earned as a taxi driver.

When I was in my third year at Namisho High School, the baseball team played at Koshien Stadium in the summer. But I couldn’t take part because I had been suspended from the team over some misconduct I was blamed for. One of the coaches hated Koreans and I felt that I was being discriminated against. Truth be told, I was wild back then.

In the summer of 1958 I visited South Korea for the first time. I went to Seoul as the cleanup hitter of a baseball team composed of Korean-Japanese high school students. We were greeted by a performance of traditional Korean folk songs, like “Arirang” and “Doraji.” I was moved, recognizing that it was the country where my mother had been born and that I was Korean. I traveled to my father’s hometown and visited his grave on my way from Daegu to Masan. My grandparents were in good health, and my grandmother caressed my face over and over. For me, South Korea is my real parent and Japan is my foster parent. And I’m a man of Hiroshima, I think, born and bred here.

Mr. Harimoto joined the Toei Flyers, a professional baseball team in the Pacific League, in 1959, and received an award for his rookie performance. In 1961, he won his first batting title. The next year, Mr. Harimoto was selected the Most Valuable Player (MVP) and led the team to victory in Japan’s professional baseball championship. He was dubbed a “hitting machine.” In 1966 he obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate.

From my first professional contract, which paid me two million yen, I gave one million yen to my older brother so he could buy a plot of land in Danbara-hinode town and build a house. I wanted to take my mother out of that small room where we had been living. As a professional baseball player, the handicap I suffered to my right hand could have been a fatal blow to my career. Even after games, I had to keep swinging my bat. During my 23 years as a player, I swung my bat every day, right up until the day before I retired.

My older brother advised me to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. No one knows when an A-bomb disease might develop. During the baseball seasons, I was so preoccupied that I took no notice of it. But I hated the off-season health checkups. I was so worried that something would turn up. That feeling of terror is still with me, too. Because of this fear, the A-bomb survivors haven’t really seen “the end of the war.”

I didn’t set out trying to hide my A-bomb experience when I became a professional baseball player. But I thought: if no one asks me, I don’t need to speak about it. During my childhood, those who didn’t experience the atomic bombing gave odd looks at the survivors with keloid scars. There was the widespread belief that “You’ll catch something if you go near them.”

When I moved to the Yomiuri Giants in 1976, I came to the old Hiroshima Municipal Stadium for some of the games. On my way to and from the stadium, I saw the Atomic Bomb Dome. I couldn’t help remembering the day of the bombing and my eldest sister’s death.

I began to speak about my A-bomb experience when I was about 65 years old. I saw a young person on a TV program say: “I don’t know about the war. I had nothing to do with it.” The comment upset me and I thought: “That’s not right.”

We mustn’t forget that a great number of people fell victim to the atomic bombing. I managed to survive, as Hijiyama Hill helped shield me from the blast. But my sister died. Because I’m part of the last generation of those who can speak from personal experience about the bombing, I felt I had a duty to hand down the truth. I offered my help to a petition drive seeking the elimination of nuclear weapons and I responded to other calls for my support from peace-related organizations.

Which is more important: protecting human lives or holding onto nuclear weapons? These two things are poles apart. It’s inhuman to permit the existence of weapons that can annihilate people in an instant, when they’re just trying their best to live.

It’s sad to hear about North Korea’s nuclear tests and artillery attacks on South Korea. People of the same ethnic group have been torn apart and are feuding with one another, and the aims sought by the major powers have had a hand in it. North Korea should stop its nuclear weapons development. In order to make this happen, though, the major powers must abandon their nuclear weapons first. Otherwise, their demands aren’t persuasive.

I wish that U.S. President Barack Obama and other world leaders would come to see the artifacts on display at the Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima and the Atomic Bomb Museum in Nagasaki. I want them to think seriously about what would happen to their parents, whom they respect, and their wives and their children, whom they love, if a nuclear weapon is used. I want them to hold an international conference in the A-bombed city to rack their brains for the good of humanity and pursue the elimination of nuclear weapons from our world. Human beings should come together and work hard for peace and happiness, rather than killing one another.

Isao Harimoto

Mr. Harimoto was born in Hiroshima in June 1940. His career batting average was .319. He hit 504 home runs and drove in 1,676 runs. He was elected to Japan’s Baseball Hall of Fame in 1990. He also made efforts to help establish and develop a professional league for baseball in South Korea, which came into existence in 1982. Mr. Harimoto now lives in Ota Ward, Tokyo.

(Originally published on January 4, 2011)

Isao Harimoto, 70, has a Korean name: Jang Hun. Mr. Harimoto is a second-generation Korean-Japanese born in Hiroshima. He is also an A-bomb survivor. Fighting baseless racial discrimination and the fear of the aftereffects of radiation, Mr. Harimoto set a number of professional baseball records, including winning the batting title seven times and producing a total of 3,085 hits. He holds a deep emotional attachment toward his hometown of Hiroshima and strong hopes for the elimination of the world’s nuclear weapons as well as peace on the Korean Peninsula, which remains divided. In this article, the Chugoku Shimbun will relate Mr. Harimoto’s story, which he shared during an interview in Hiroshima.

A-bomb memories vividly recalled

I heard that my father was encouraged to come to Hiroshima by his younger brother, who had already settled down here. They pulled a two-wheeled cart through the city and sold scrap iron and secondhand items. My father felt he could earn a living that way and so he invited his mother, older brother, and two older sisters to move to Japan. It was the spring of 1939.

I was born in Ozu town, now part of Minami Ward. Near the Higashi Ohashi Bridge, still straddling the Enko River, there was a row house where Korean people lived. From the days of my earliest recollections, I played on the bank of the river. One winter when I was four, out on the bank baking sweet potatoes with my friend, a three-wheeled truck backed up and struck me. I suffered serious burns to my right hand when it was jarred into the fire, and my fourth and fifth fingers became stuck together. The driver fled, and my uncle, unable to stand by idly, appealed to the police. But I heard that they turned him away, telling him, “You’re Korean.”

Mr. Harimoto’s father Jang Sang Jeong came from Changnyeong-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do and his mother Pak Sun Bun from Hapcheon-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do. The number of Korean immigrants to Hiroshima increased from the mid-1920s due to Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910. In 1940, when Mr. Harimoto was born, roughly 38,000 Koreans lived in Hiroshima Prefecture, according to records of Japan’s Home Ministry. In addition, due to the application of the National Conscription Ordinance to those on the Korean Peninsula in 1944, in the wake of the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, a large number of Koreans were exposed to the atomic bombing in Hiroshima.

When the bomb exploded, I was at a row house in Danbara-shinmachi, about 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. There was a flash and an enormous roar. The next thing I knew my mother was shielding me and my sister, three years older, with her body, though her back was covered in blood due to flying shards of glass. We were urged to run, in Korean, and we fled to a vineyard. Even now, 65 years after the bombing, I can still vividly recall the people groaning and the strange stench. There were dozens of people in the vineyard. When I tried to go see people who were screaming for water and jumping into a canal nearby, my mother stopped me.

My eldest sister had been mobilized at a work site at Hijiyama Hill or thereabouts. My older brother and others went to look for her and they carried her back on a stretcher. She was suffering terrible burns, on her face, too. I was shocked to see a human being, the sister I so admired, transformed into such a state. I remember bringing charred grapes to her mouth. I have no idea how many days passed after that, but one day I heard my mother crying and I knew my sister was dead.

The name of Mr. Harimoto’s eldest sister, Jang Jeom Ja, is recorded in the register for the A-bomb victims, housed in the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in Hiroshima. According to the application form, she was exposed to the atomic bombing in Tsurumi town in Naka Ward at the age of 12. Students of the First National School (now, Danbara Junior High School), among others, were mobilized to work all over Tsurumi town, west of Hijiyama Hill, for the war effort, helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. Mr. Harimoto confirmed the record of the death of his eldest sister for the first time on this occasion.

Yes, this must be my eldest sister. I guess my older brother (Seye Ol, who died in 1996 at the age of 64) filed the application, since my mother was unable to write in Japanese. Perhaps because of the cultural differences, my mother did not keep any of her belongings and, until her death, did not talk to us about her. (Mr. Harimoto’s mother died in 1985 at the age of 83.) I’m 70 now and I’ve finally learned where my sister experienced the atomic bombing. I feel grateful for that.

Mother’s struggle stirs desire to turn professional

The war was over, but we had no home. For a while we lived under the Higashi Ohashi Bridge with others, including a Korean family. As my father was the eldest son, he went back to South Korea ahead of us. But then he died. My mother, upon hearing that a ship, operating illegally, had capsized off the coast of Shimonoseki in Yamaguchi Prefecture after leaving Hiroshima, gave up returning to South Korea out of concern for our safety. So our family of four began living in a small, rented room in Shinonome town (now, Kami-shinonome in Minami Ward).

From watching other people cook, my mother learned how to make “horumon yaki,” grilling the guts of chickens and other animals that my older brother bought at the black market. She sold unrefined sake, too. She worked so doggedly to provide for us that I hardly saw her sleep.

I was a naughty child from the time I entered Hijiyama Elementary School. It was partly my nature, and I was big physically, too. In summer, I went swimming in the Enko River in only my underwear. I stood up against older students who bullied my Korean friends. In alleys of the Danbara district, I also played “menko,” a game where you throw a thick card at the ground to try to flip over the card of an opponent, as well as “ramune,” a game with marbles.

I started playing baseball when I was in the fifth grade at elementary school. An older boy in the neighborhood invited me to play, and I hit a double in my first baseball game. I loved it and I begged him to keep letting me play. Although I had had surgery on my right hand, I still didn’t have complete control over my fingers and so I couldn’t throw the ball so far. But I practiced throwing against a wall and I was able to completely alter myself into a left-handed pitcher and hitter.

Around then, in 1950, the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, the city’s professional baseball team, was established. Tetsuharu Kawakami and Noboru Aota, players I admired, came to the stadium in Minami Kanon (now, the Coca Cola West Hiroshima Stadium in Nishi Ward). As I had no money, I climbed a tree outside the stadium to watch the game. When I peeked into their lodgings, I saw white rice and steaks on the table. I was surprised at their well-heeled life, which led to my wish to become a professional baseball player.

I might have joined a swimming club, though, if there had been a swimming pool at Danbara Junior High School at the time. Whether that was fortunate or not, there wasn’t and so I kept playing baseball. When I entered my third year of junior high school, I hoped to go to Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School and star at the big high school baseball tournament at Koshien Stadium. Kazuyoshi Yamamoto, who went to Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School from Midorimachi Junior High School in Minami Ward and later became a slugger for the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, was two years older than me. He let me take part in the baseball practice at his school. But I failed to get admitted. It was a small thing, but at Danbara Junior High I once hit an older student in a fight with the soccer team over the use of the school ground. Koryo High School also refused me, saying that I was a roughneck.

While working in the cafeteria at Matsumoto Commercial High School (now, Setouchi High School), I attended night school there and continued to play baseball. But I was determined to play at Koshien Stadium. For the second semester, I transferred to Namisho High School (now, Namisho High School at Osaka University of Health and Sport Sciences) in Osaka Prefecture, which had a powerful baseball team. The manager of the baseball team at Matsumoto Commercial High School believed that I could become a good player. My older brother persuaded my mother to let me pursue my dream, telling her, “He won’t amount to much if we leave him where he is.” He then sent me money for my school expenses from his wages earned as a taxi driver.

When I was in my third year at Namisho High School, the baseball team played at Koshien Stadium in the summer. But I couldn’t take part because I had been suspended from the team over some misconduct I was blamed for. One of the coaches hated Koreans and I felt that I was being discriminated against. Truth be told, I was wild back then.

In the summer of 1958 I visited South Korea for the first time. I went to Seoul as the cleanup hitter of a baseball team composed of Korean-Japanese high school students. We were greeted by a performance of traditional Korean folk songs, like “Arirang” and “Doraji.” I was moved, recognizing that it was the country where my mother had been born and that I was Korean. I traveled to my father’s hometown and visited his grave on my way from Daegu to Masan. My grandparents were in good health, and my grandmother caressed my face over and over. For me, South Korea is my real parent and Japan is my foster parent. And I’m a man of Hiroshima, I think, born and bred here.

Appealing for peace and nuclear abolition

Mr. Harimoto joined the Toei Flyers, a professional baseball team in the Pacific League, in 1959, and received an award for his rookie performance. In 1961, he won his first batting title. The next year, Mr. Harimoto was selected the Most Valuable Player (MVP) and led the team to victory in Japan’s professional baseball championship. He was dubbed a “hitting machine.” In 1966 he obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate.

From my first professional contract, which paid me two million yen, I gave one million yen to my older brother so he could buy a plot of land in Danbara-hinode town and build a house. I wanted to take my mother out of that small room where we had been living. As a professional baseball player, the handicap I suffered to my right hand could have been a fatal blow to my career. Even after games, I had to keep swinging my bat. During my 23 years as a player, I swung my bat every day, right up until the day before I retired.

My older brother advised me to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. No one knows when an A-bomb disease might develop. During the baseball seasons, I was so preoccupied that I took no notice of it. But I hated the off-season health checkups. I was so worried that something would turn up. That feeling of terror is still with me, too. Because of this fear, the A-bomb survivors haven’t really seen “the end of the war.”

I didn’t set out trying to hide my A-bomb experience when I became a professional baseball player. But I thought: if no one asks me, I don’t need to speak about it. During my childhood, those who didn’t experience the atomic bombing gave odd looks at the survivors with keloid scars. There was the widespread belief that “You’ll catch something if you go near them.”

When I moved to the Yomiuri Giants in 1976, I came to the old Hiroshima Municipal Stadium for some of the games. On my way to and from the stadium, I saw the Atomic Bomb Dome. I couldn’t help remembering the day of the bombing and my eldest sister’s death.

I began to speak about my A-bomb experience when I was about 65 years old. I saw a young person on a TV program say: “I don’t know about the war. I had nothing to do with it.” The comment upset me and I thought: “That’s not right.”

We mustn’t forget that a great number of people fell victim to the atomic bombing. I managed to survive, as Hijiyama Hill helped shield me from the blast. But my sister died. Because I’m part of the last generation of those who can speak from personal experience about the bombing, I felt I had a duty to hand down the truth. I offered my help to a petition drive seeking the elimination of nuclear weapons and I responded to other calls for my support from peace-related organizations.

Which is more important: protecting human lives or holding onto nuclear weapons? These two things are poles apart. It’s inhuman to permit the existence of weapons that can annihilate people in an instant, when they’re just trying their best to live.

It’s sad to hear about North Korea’s nuclear tests and artillery attacks on South Korea. People of the same ethnic group have been torn apart and are feuding with one another, and the aims sought by the major powers have had a hand in it. North Korea should stop its nuclear weapons development. In order to make this happen, though, the major powers must abandon their nuclear weapons first. Otherwise, their demands aren’t persuasive.

I wish that U.S. President Barack Obama and other world leaders would come to see the artifacts on display at the Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima and the Atomic Bomb Museum in Nagasaki. I want them to think seriously about what would happen to their parents, whom they respect, and their wives and their children, whom they love, if a nuclear weapon is used. I want them to hold an international conference in the A-bombed city to rack their brains for the good of humanity and pursue the elimination of nuclear weapons from our world. Human beings should come together and work hard for peace and happiness, rather than killing one another.

Isao Harimoto

Mr. Harimoto was born in Hiroshima in June 1940. His career batting average was .319. He hit 504 home runs and drove in 1,676 runs. He was elected to Japan’s Baseball Hall of Fame in 1990. He also made efforts to help establish and develop a professional league for baseball in South Korea, which came into existence in 1982. Mr. Harimoto now lives in Ota Ward, Tokyo.

(Originally published on January 4, 2011)