Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Mobilized Students 3

Jun. 22, 2015

Students avoid bombing through evacuation to rural villages

The Chugoku Shimbun edition of July 28, 1945 noted that the sixth phase of work to create fire lanes cutting across the Hiroshima delta, organized by the City of Hiroshima and deemed preparations for “a fight to the end,” began on July 26. To prepare for “the arrival of enemy planes,” a large number of male and female students were mobilized to help create large-scale “evacuation sites” in the city.

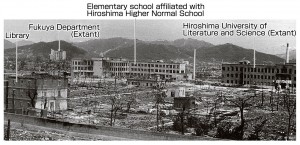

On August 6, the atomic bomb exploded above the heads of mobilized students in many parts of the city, including the Nakajima, Koami-cho, and Tsurumi-cho districts. (The Nakajima area is now the site of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.) Scores of students in these “service corps,” from a variety of middle schools, lost their lives, most of them first- and second-year students. According to a survey by the Peace Memorial Museum conducted in 2004, 82 percent of the roughly 7200 students who became victims were mobilized to help demolish homes to create these fire lanes.

Feeling survivor’s guilt

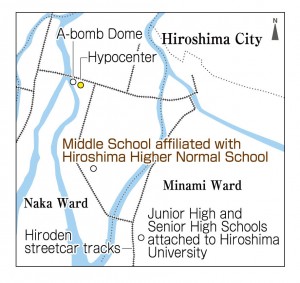

“Why were we the only ones who survived? We struggled with guilt and it took many long years for us to put down our accounts,” said Isamu Takada, 83, a resident of Minami Ward, as he exchanged a look with Shunichiro Arai, also 83 and a resident of Minami Ward. In 1984, Mr. Takada and Mr. Arai, along with former classmates, compiled a book entitled Showa Nijunen no Kiroku (A Record of 1945), running 377 pages. The book is based on their memories of the war from diaries they had been keeping as first-year students at the middle school affiliated with the Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now Hiroshima University).

A month after they entered the school, the first-year students, along with students at other middle schools, began to be mobilized for the war effort, assigned to work at military facilities and other locations. The ceremony to launch their service corps was planned for July 8, but then was canceled without explanation. In his diary entry on July 17, Mr. Arai wrote, “The decision was finally made to send the first-year students from our school to work in rural villages.” From this entry can be sensed the sincerity and enthusiasm of the mobilized students.

On July 20, around 100 first-year students from the school departed for the village of Hara (now the city of Higashihiroshima). In addition, 35 first-year students from a special science course, who were selected for this course in the previous year by the central government, left for the city of Tojo (now Shobara) on July 9, together with the second- and third-year students.

There was a secret objective, held by some of the teachers and others involved, in sending these students into the countryside. Under the guise of helping rural communities, the decision was made to evacuate the first- and second-year students of the ordinary classes, along with the students in the special science course who went to Tojo, because “the teachers sensed it was very dangerous for the students to stay in the city of Hiroshima.” An essay found in A Record of 1945, written by Tsutomu Miyaoka, one of the teachers charged with mobilizing the student body, reveals that the evacuation covered all first- and second-year students.

With air raids intensifying on major Japanese cities, including the city of Kure, which neighbors Hiroshima, Mr. Miyaoka and others searched for places in the prefecture that would take in the students. Thanks to their efforts, the first-year students were able to stay in several groups at temples and shrines in the village of Hara, where the home of a teacher’s parents was located, and the second-year students, with the aid of their parents, were evacuated to the village of Tono, now a part of Higashihiroshima City.

On August 6, Mr. Takada and Mr. Arai, because of their hard work at the farm labor they weren’t accustomed to, were chosen to bring some documents to their school in Hiroshima. In a group of five students, they headed for the city on foot and by train. Along the way, according to Mr. Arai’s diary, they witnessed “a huge flash and billowing smoke” when they reached Hachihonmatsu Station and were waiting for the train, yet they continued on.

Classmates from elementary school among the victims

On August 8, Mr. Takada found the cold, lifeless body of his father, Hajime, 52, at the site of his family’s home in Teppo-cho (now Naka Ward). His mother, Yoshiko, 44, and eldest brother, Masahiro, 22, also passed away soon after the bombing.

The lives of Mr. Arai’s family were spared, but he was shocked by the deaths of former classmates from his elementary school days. The diary he had continued writing, even while staying in Hara, was given to him by Yoshitora Masaki, 13, who went on to study at Hiroshima First Middle School.

The two men avoided speaking about their experiences of the atomic bombing after the war. The surviving students at the school were cruelly viewed as having “fled” from the city. Many first-year students who survived later assumed positions in which they helped create the strong economic growth of Japan’s postwar period.

After turning 50, however, they felt compelled to put together A Record of 1945 because “the first-year students at other schools who lost their lives were former classmates of ours in elementary school.” They also found out the fates of 10 classmates who had stayed behind in Hiroshima because of poor health or other reasons and died in the atomic bombing. In 2005, while eliciting the support of the school’s alumni association, they made efforts to build a memorial on the school grounds in Midori, Minami Ward to console the victims of the atomic bombing and the war.

Since then, Mr. Arai has been actively sharing his experience. He said, “I can’t stay silent when there’s an increasing number of dangerous comments being made by politicians who don’t know the suffering of war.” Mr. Takada remains reluctant to talk about his experience in public, but he explained why he agreed to this interview, saying, “I’d like to tell how, despite the war conditions, our teachers showed concern for the students, and calm judgment, and acted accordingly.”

Both men stress that the deaths of the mobilized students must be discussed not only as a tragic event of the past, but also as a lesson and warning for the present and future.

(Originally published on June 22, 2015)