Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Donated Records

Oct. 24, 2014

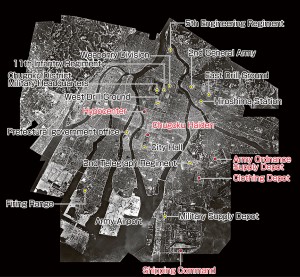

Shedding light on August 6 in Hiroshima, a military city

In the past, Hiroshima was a military city. “It is not an exaggeration to say that the entire city was filled with army facilities and organizations for military operations,” states Volume 1 of the "Record of the A-Bomb Disaster," issued by the City of Hiroshima, which describes what Hiroshima was like during World War II. Many citizens and students were mobilized to work at munitions companies and factories, then compelled to suffer the tragedy of August 6, 1945. In a response to a call from the Chugoku Shimbun, a range of documents related to the atomic bombing were shared, including records which show the nature of Hiroshima as a military city. The newspaper would like to shed light on this side of Hiroshima, as well as the city’s evolution since that time, which are fading from memory.

Notes on the former Army Clothing Depot

The red-brick warehouses are “grave markers” for the victims

In the city stands a complex of A-bombed buildings that distills the history of Hiroshima but lacks even a sign of explanation. This site, which once served as the Army Clothing Depot, is located in today’s Deshio district, in Minami Ward. Four huge ferroconcrete warehouses with red bricks covering the outer walls--the No. 10 to No. 13 warehouses--were constructed in 1913 and remain there today.

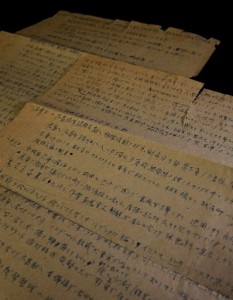

Located about 2.7 kilometers from the hypocenter, the warehouses of the Clothing Depot did not burn in the A-bomb blaze. In the aftermath of the bombing, the wounded poured into the warehouses. Tadao Hiraguri, then 36, who was working at a transportation unit, wrote with a fountain pen on two sheets of rough paper about his experiences from August 6 to 17, including a notation which reads: “Stayed that night at the No. 10 warehouse.”

Mr. Hiraguri was at home in Akebonocho (today’s Higashikaniya-cho in Higashi Ward) when the A-bomb exploded, and fled to his brother-in-law’s house in Yaga-machi (part of today’s Higashi Ward) with his wife and his child. He walked through the charred city from August 7 to search for his niece, who was a second-year student at today’s Minami Senior High School, as she did not return from her work as a mobilized student, helping to dismantle homes to create a fire lane in the event of air raids.

“Went to the Clothing Depot,” wrote Mr. Hiraguri, “which has taken in a large number of wounded. Looked for my niece, but couldn’t find her.” The many injured people in the warehouses were left lying on the floors.

Mr. Hiraguri stayed at the Clothing Depot from August 11 to help with relief efforts. “Made the rounds and carried dead bodies on a stretcher to cremate behind the buildings.” He carried on with “the same work on the 12th, 13th, and 14th.” The bodies were cremated in holes dug on the grounds.

Iwao Nakanishi, 84, a resident of Yasuura-cho, Kure City, gazed at the warehouses, standing in an L-shape. Biting his lip, he said, “I still hear the groans of the people who were injured.” He experienced the bombing while in front of the No. 13 warehouse, where he was working as a mobilized student. He recalled putting zinc oil on the wounded who had fled there. At the time, he was a fourth-year student at the middle school attached to Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now part of Hiroshima University).

This past March, Mr. Nakanishi formed an association to call for the preservation of the site of the former Clothing Depot and held a memorial gathering in August to pray for the repose of the victims. “The red-brick warehouses are the grave markers for the many victims who died here. They also convey the history of the city’s reconstruction.” He is asking that the Hiroshima city and prefectural governments make good use of the buildings.

Each warehouse is 15 meters tall, 26 meters wide, and 91 to 105 meters long. The total land area is 17 hectares. From January 1946, the warehouses were used as classrooms for today’s Minami Senior High School, and from April of that year, for Hiroshima Higher Normal School, which became Hiroshima University’s Faculty of Education in 1949 under the new education system. The former Army Ordnance Supply Depot, where Hiroshima University’s Kasumi Campus is located today, was used by the prefectural government from June 1946. In this way, the former military sites in these areas became bases for the reconstruction of the city from the ashes of the A-bombing.

In 1952, the Prefectural Board of Education acquired the three warehouses and the land, in an exchange of property, from the national government. The new buildings of Minami Senior High School and Hiroshima Technical High School were also built on the site of the former Clothing Depot. The three warehouses owned by the prefectural government were used as warehouses by Nippon Tsuun (Nippon Express) and the warehouse owned by the national government was used as the “Kunpu-ryo” domitory for Hiroshima University until 1995.

Since then, there have been various ideas for the use of the warehouses, such as the Seto Inland Sea Culture Museum and an annex of the Hermitage Museum, proposed by the prefectural government, and the Paper Crane Museum, proposed by the city government. However, none of these ideas has been pursued. Because the cost of the seismic retrofitting for each warehouse is estimated at 2.1 billion yen, according to the Property Administration Division of Hiroshima Prefecture, the buildings, among the first ferroconcrete warehouses in Japan, have been left unused.

Military uniforms and boots were manufactured at the Clothing Depot. As Hiroshima became a base to send troops off to war, “thousands of men and women” worked here (noted the Chugoku Shimbun on July 10, 1922). There was even a nursery. Takeshi Nishigaki, 96, who lives in Miyake, Saeki Ward, said, “Today, only a few people know how Hiroshima developed as a military city and how the area was a bustling place in those days.” He taught at a school for youth on the grounds, where teenage boys and girls were working in the factory.

After Mr. Hiraguri helped with further relief efforts in Oda Village (part of today’s Akitakata City), where goods had been evacuated to various places in anticipation of air raids, he settled there in the village with his family and became a carpenter. Because his notes mention where he settled, they were probably written in the 1950s. Tamie Hashimoto, 78, Mr. Hiraguri’s eldest daughter and now a resident of Nakasuji, Asaminami Ward, has kept the notes as a memento of her father. When he died in 1987, she found them at her father’s home. When Ms. Hashimoto visited the former Clothing Depot with Mr. Nakanishi and Mr. Nishigaki, she said, “My father made his notes to convey the record of this place to future generations, to the extent that he could. So I hope these buildings will be used in a meaningful way.” With deep emotion, she looked up at the iron shutters that were warped by the force of the A-bomb blast.

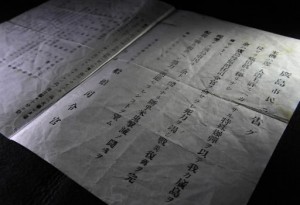

Flyers of the notice issued by the Shipping Command

18 locations for the wounded are mentioned

“American bombers finally attacked our city, Hiroshima, with a special bomb, which is unacceptable from a humanitarian viewpoint,” begins the notice that was distributed and posted on August 7, 1945. It reports that relief stations to accommodate the wounded were established at 18 locations, including at the East Drill Ground, to the north of Hiroshima Station, and in the western side of the city, in today’s Hatsukaichi City. The contact addresses are also listed, dividing the city into four areas for relief activities.

The notice was issued by Bunro Saeki, who died in 1967 at the age of 77. He was the lieutenant general of the Army’s Shipping Command and the units under his authority did not suffer serious damage as they were located in Ujina-machi (today’s Ujina Kaigan, Minami Ward). Mr. Saeki and his soldiers launched their relief activities soon after the atomic bombing on August 6. On August 7, Mr. Saeki took charge of security in the city and also directed the restoration efforts.

None of the original flyers are held at the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives or at the Hiroshima Municipal Archives. Denkichi Yamamoto, 85, a resident of Saeki Ward, told about the existence of an original flyer, kept by Shinya Takasugi, 85, who lives in the city of Hakodate in Hokkaido. Mr. Yamamoto and Mr. Takasugi entered the 10th training unit of the Marine Training Division at the same time. The unit was designed to train soldiers for special missions--in fact, suicide attacks--on the sea. Mr. Takasugi, Mr. Yamamoto, and others, who were teenagers who had volunteered to become special officer candidates, saw the mushroom cloud rising over Hiroshima from their base at Konoura in Etajima (part of today’s Etajima City).

Some years later, Mr. Saeki wrote an overview of the recovery efforts from war damage that were made in the city of Hiroshima. According to this document, preserved at the National Institute for Defense Studies, the 10th training unit and other units had reached the area near Minamiohashi Bridge, which spanned the Motoyasu River, at 1:10 p.m. on August 6, to extinguish fires and rescue the wounded.

On August 8, Mr. Takasugi went to Ujina Port, bringing rice, "miso," and other supplies by ship. He said he found this flyer on the ground at the port, along with people who had suffered severe burns. He said quietly, “I didn’t want to talk about what I saw in Hiroshima after I came back to my hometown, Hakodate. Even today, I don’t feel like talking about it.”

Mr. Yamamoto helped cremate the victims, too. Ten years ago, he received a photocopy of the flyer by mail. He wrote “preserve permanently” on the envelope. Mr. Takasugi had written in his letter, “I can never forget it.”

Survey of the A-bomb damage, conducted by Chugoku Haiden

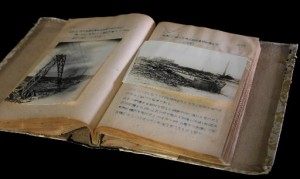

Photographs clearly show burned and destroyed city

An early report was made in connection with a survey of the damage wrought by the atomic bombing. The Hiroshima branch of Chugoku Haiden (now the Chugoku Electric Power Company) conducted the survey and issued a report on the damage done to electric power facilities. Volume 5 of the "Record of the A-Bomb Disaster" highlights this report, but the original document cannot be located.

On August 6, 1945, the area within about two kilometers from the hypocenter was completely destroyed, including electric power facilities. With support from the Shipping Command to restore the equipment, the company was able to restore some electricity use from the following day. By August 20, power was back to 30% of the remaining homes in the delta area, and by the end of November, to the whole area affected by the atomic bombing. The survey was carried out from November to the end of that year, and the report was published in March of 1946.

The 57-page report was printed on rough paper with about 30 clear photographs attached, including a photo of the burnt-out power plant at Senda-machi (part of today’s Naka Ward) and another photo of a fallen iron tower. Yoshita Kishimoto, who had run a photography studio since prior to the war, was asked by the electric company to take photos to record the effects of the bombing. Mr. Kishimoto died in 1989 at the age of 87.

Kimihiko Iwamuro, who passed away in 1993 at the age of 72, had kept an original print of the report. He was an employee at the Hiroshima branch of Chugoku Haiden at the time of the atomic bombing. His eldest son, Joichi, 67, a resident of Aosaki, Minami Ward, found it among the things his father left behind.

According to the Record of the A-Bomb Disaster, the report was translated into English in April 1951 and submitted to the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. According to the Chugoku Electric Power Company, Mr. Iwamuro was then working in the public relations section of the survey office at Chugoku Haiden’s headquarters.

Joichi remembers, in his childhood, offering silent prayers with his father at home every year on August 6. “My father never talked about the atomic bombing, but I think he wanted to convey something by keeping the report. So I couldn’t dispose of the report, either,” Joichi said. His late mother told him that his father experienced the bombing while on his way to work.

Chugoku Haiden’s headquarters was located about 800 meters from the hypocenter, and the Hiroshima branch office at Togiya-cho (today’s Tatemachi, Naka Ward), lay about 500 meters from the hypocenter. A total of 274 employees died due to the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on October 13, 2014)