Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Students study in open-air classrooms in “A-bomb desert”

Mar. 19, 2015

The atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 upended their lives and scarred their futures. Around the time of the atomic bombing, many students above the third grade of Hiroshima’s national schools (today’s elementary schools) were temporarily living in rural locations because urban areas were targets of air strikes. Some children lived with relatives in the countryside, while others were part of group evacuations. At the same time, many of the more than 15,000 children who continued to live with their parents in the city were killed or suffered serious injuries. What awaited the survivors after the war were lives in the “A-bomb desert.” They had no choice but to endure hunger and the elements. Their classes were held out on the school grounds or in classrooms exposed to the wind and rain. The Chugoku Shimbun and former students visited some of the schools where children made fresh starts following the devastation of the atomic bombing.

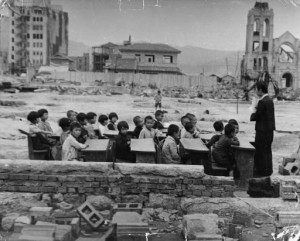

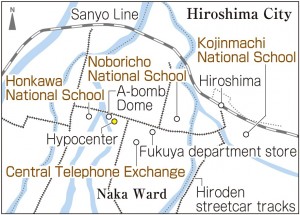

Noboricho Park is surrounded on all four sides by tall buildings. Kengo Kurata, 76, said the photo of the “open-air classroom,” in which he appears, was taken on the east side of the park. “I don’t think young people today would believe it,” said Mr. Kurata, and his four former classmates nodded.

The photo shows some 20 second-graders of Noboricho National School attending class in the schoolyard. No textbooks or notebooks can be seen, let alone a blackboard. The photo was taken in the spring of 1946 by an Australian war correspondent who came to Hiroshima with the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces.

Mr. Kurata and his relatives happened to be away from Hiroshima on August 6. He was the youngest of eight siblings. His parents ran a hardware store in Hashimoto-cho in downtown Hiroshima. His eldest brother Shinjiro, then 26 and a fire fighter, and his sister Haruyo, then 13 and a second-year student at Shintoku Girls’ High School, were killed in the atomic bombing. The surviving family members temporarily lived with relatives whose house had not burned. The following March they returned to the city and built a shack.

School opened again in October 1945, using some of the rooms at the Hiroshima Central Broadcasting building, which did not burn down, located in Kami-nagarekawa-cho (now Nobori-cho, Naka Ward), and later rooms at the Hiroshima Central Telephone Exchange in Fukuromachi. But classes eventually had to resume at the school itself because of restoration work on those other buildings. The schoolyard was still filled with debris.

“We used coal or tangerine boxes as desks,” said Mr. Kurata, recalling the time they moved from the telephone office to the school grounds. At the telephone office, at least the students were not exposed to the rain. Takako Suguri, 76, also returned to Hiroshima from the countryside. “Students in the lower grades helped remove the debris, too,” she said. She was born and raised at Shokoji Temple in Nobori-cho, and her grandparents fell victim to the atomic bombing.

By June 1946, a simple building with 10 classrooms had been hastily constructed. With children of returnees from overseas and those who moved in from surrounding areas, there were too many students for the building to accommodate. They were divided into two groups, with one group taking lessons in the morning, the other in the afternoon.

Parents plowed the school grounds and students grew sweet potatoes. Food rations were often delayed or suspended in Hiroshima, and, in the city’s newsletter of June 1946, Mayor Shichiro Kihara asked residents to make use of all available land to grow food. At school, the children were instructed in how to cook wild plants.

School records indicate that the school lunch service resumed in July 1946. Children were given powdered skim milk, which was among the relief items. They also ate dumplings made from dried horseweed and flour, or made from sweet potato powder and seaweed. “They tasted terrible, but we had no choice but to eat them,” said one of the former students, the others agreeing with wry smiles.

In 1947, the School Education Act came into effect, and Noboricho National School was renamed Noboricho Elementary School. But students had to continue studying in the open-air classrooms with ceilings made of reed screens. Lacking resources, the city was unable to construct school buildings as quickly as hoped. Parents formed a committee to raise funds for a new school building. Finally, in 1949, a two-story school building was completed at the location where the school now stands. The building, with its 28 classrooms, cost 11 million yen to construct, half of which was paid by the city government.

Mr. Kurata was a fifth-grader when classes began in the new school building. He remembers taking a one-day school trip to Kosan-ji Temple in Onomichi when he was in sixth grade. The graduation album, with a graduating class of 184 students, included a photo of the school library.

“They joined hands and rebuilt the school amid the ruins of war. They did a remarkable job,” said Mr. Kurata. He went on to study at Noboricho Junior High School and Motomachi High School. After finishing high school, he took over his parents’ hardware shop and got married. When he moved to the Funairi Minami area in the same ward, he still helped the community in which he grew up. He helped build a warehouse for emergency supplies at Noboricho Elementary School, where his two daughters studied.

After they turned 60, Mr. Kurata and his classmates began to get together more often and share memories of how the devastated city was revived.

It was a chilly day at Noboricho Park, but they enjoyed talking about the days when they swam in the Kyobashi River or played baseball on Chuo Street, now a busy road. They hope that younger generations will come to know not only the memories of destruction, but also how people lived through the post-war days, which is less often told.

Honkawa National School was located closest to the hypocenter, about 410 meters away. According to the Record of the A-bomb Disaster, issued by the City of Hiroshima, 218 students at the school were killed instantly on August 6, 1945. Still, the overall picture of the casualties here is unclear. The school building was constructed in 1928 as the first three-story concrete school building in Hiroshima. Despite the bombing, its framework remained and the school resumed classes in February 1946.

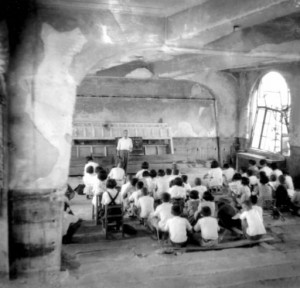

Kojiro Taida, 77, remembers how the walls and floors of the school building were burned and the windows had no window panes. “The wind and rain came through the windows,” he said. After returning from the countryside, where he had stayed during the war, he entered Honkawa Elementary School because Kodo National School in Nekoya-cho (now part of Naka Ward), which he used to attend, had been seriously damaged and was closed.

His father Tokusaburo, then 55, and brother Akinori, then 15, were killed by the blast at their home in Nekoya-cho. Tokusaburo ran a confectionery shop, and Akinori was a third-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School. With six children, including Kojiro, to raise, his mother Takiko, then 35, took a relative’s advice and decided to continue running her husband’s shop.

The window frames of the school building were warped by the A-bomb blast. In winter, straw mats were hung over the windows but did not keep out the chill. The roof was often leaky. A photo taken on the day of the athletic meet in autumn, two years after the bombing, shows windows still lacking window panes.

Honkawa Elementary School was close to the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the A-bomb Dome), which was heavily damaged. Many people visited the school to conduct inspections, including people from the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, or intellectuals from Tokyo. Students often received pencils and other stationery from these visitors, but they were nevertheless always short of supplies.

Many of his classmates lost their parents. Mr. Taida remembers playing a simple version of baseball--played without a second base--and swimming in the Honkawa River, which runs near the school.

When the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, the city’s professional baseball team, was established in January 1950, he went to see the ceremony held at the former West Military Drill Ground site. The baseball team was formed with the aim of lifting the spirits of the Hiroshima people. When the team had a game at Hiroshima Sogo Ground Baseball Park (now part of Nishi Ward), Mr. Taida, then a sixth-grader, voluntarily delivered candy which was sold at a booth and collected the money for it. “Baseball was my only pleasure, and I got to see the game for free if I helped,” he said with a smile.

After finishing junior high school, he worked at his mother’s shop in the daytime and studied in the evening course at Motomachi High School. He then lent financial support to his younger brother and two sisters so they could pursue their university studies. He married in 1965, when Hiroshima was enjoying rapid economic growth. Thirteen family members, including two sons and four grandchildren, have attended Honkawa Elementary School.

Responding to our request, Mr. Taida, his son Masaaki, 46, grandson Shintaro, 10, a fourth-grader, and Yosei, 8, a second-grader, visited the school. Part of the school building was preserved and turned into Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum in 1988. The museum provides a place to learn about peace for the students attending the school, as well as some 20,000 students on school trips and others who visit the museum annually.

Masaaki said, “Even though we studied in the A-bombed building, the memories of the atomic bombing didn’t feel so fresh. I hope the students here will feel the history that’s close to them.” When they enter the fifth grade, students of Honkawa Elementary School begin explaining the museum’s exhibits to children in lower grades and parents.

Mr. Taida said he never had a special occasion to tell his story of the atomic bombing to his children or grandchildren. In calm tones, he then started talking to his grandchildren, who are around the same age as Mr. Taida was when he experienced the bombing. “You’re very fortunate that your father is with you,” he said, “But Grandpa was…”

Kojinmachi Elementary School: Students excited by hustle and bustle of black market Kojinmachi Elementary School, located 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, was completely destroyed. Classes were held in open-air classrooms until September 1948. Fumiaki Kajiya, 75, was in first grade at the time of the bombing. “When the weather was nice, it was much more pleasant than in the dark rooms in the poorly constructed building. I don’t remember anything bad about it,” he said.

When the atomic bomb exploded, Mr. Kajiya was at a nearby house in Osuga-cho (Minami Ward) that was being used as a temporary classroom in case of air raids. He was able to escape on his own, but his sister Fumiko, then 9, was trapped under a column and died instantly, which he learned later. Until the month before the bombing, they had stayed with relatives in Oasa, located in the northern part of the prefecture.

“My mother was at home and she was injured. She kept regretting that we had come back from the countryside. But I was just a child and was quick to bounce back. I was happy when I went back to school in autumn,” said Mr. Kajiya.

“There were no desks available and each student carried a wooden box to and from school. But I was excited to see the hustle and bustle of the black market around Hiroshima Station. We imitated the sales pitches of vendors, watched people bet and play Japanese chess, and sometimes earned a little cash by selling copper wire or brass we collected in the ruins. I was hungry, but felt a new era being ushered in.”

His two elder brothers came home after they were demobilized. They made their younger brother the priority and paid for his education. Mr. Kajiya graduated from Hiroshima University in 1962 and taught at elementary schools in Hiroshima until 1999. He often recalls his experiences as a boy. “Both teachers and students lived their lives to the fullest, and had strong bonds,” he said. The open-air classrooms on the charred ground were what he always remembered in getting back to the basics as an educator.

Naka Ward

Honkawa (Honkawa-cho) destroyed/burned

Fukuromachi (Fukuro-machi) destroyed/burned

Noboricho (Nobori-cho) destroyed/burned

Nakajima (Kako-machi) destroyed/burned

Otemachi (Ote-machi, closed) destroyed/burned

Hirose (Hirose-cho) destroyed/burned

Kanzaki (Funairi Naka-machi) destroyed/burned

Takeya (Tsurumi-cho) destroyed/burned

Hakushima (Nishi Hakushima-cho) destroyed/burned

Senda (Higashi Senda-machi) destroyed/burned

Seibi affiliated with Army’s Kaikosha

(Hatchobori, closed) destroyed/burned

Kodo (Nekoya-cho, closed) destroyed/burned

Funairi (Funairi Minami) usable

Eba (Eba Minami) usable

Minami Ward

Danbara (Matoba-cho) destroyed/burned

Kojinmachi (Nishi Kaniya) destroyed

Middle school attached to Hiroshima Higher Normal School (Midori-machi, Hiroshima University Attached Elementary School) destroyed/burned

Minami (Minami-machi) partially destroyed

Hijiyama (Kami Shinonome-cho) partially destroyed

Oko (Asahi) partially destroyed

First, Advanced Course (Kasumi, Danbara Junior High School) partially destroyed

Third, Advanced Course (Midori, Midorimachi Junior High School) partially destroyed

Junior High School affiliated with Hiroshima Normal School (Boys) (Shinonome, Hiroshima University Attached Shinonobe Elementary School)

partially destroyed

Ujina (Ujina Miyuki) usable

Ujina branch campus (Motoujina-machi) usable

Niho (Niho-shinmachi) usable

Kusuna (Kusuna-cho) usable

Aosaki (Aosaki) usable

Ninoshima (Ninoshima-cho) usable

Higashi Ward

Ushita (Ushita Asahi) partially destroyed

Onaga (Yamane-cho) burned

Yaga (Yaga) usable

Nishi Ward

Tenma (Tenma-cho) destroyed/burned

Kanon (Minamikanon, Minamikanon Elementary School) destroyed/burned

Misasa (Misasa-machi) destroyed/burned

Oshiba (Oshiba) partially destroyed

Second, Advanced (Minamikanon, Minamikanon Junior High School)

partially destroyed

Fourth, Advanced (Nakahiro-machi) burned

Koi (Koiue) usable

Furuta (Furuenishi-machi) usable

Kusatsu (Kusatsu Higashi) usable

Data from Record of the A-Bomb Disaster published by the City of Hiroshima and the 1946 Shisei-yoran, a guide to the city’s administration.

*It is unknown whether Fourth National School had students.

Fluctuations in number of students

May 1, 1945 41,638

1946 19,201

1947 23,580

1948 26,710

1949 30,431

1950 33,951

(25,836 evacuated to countryside in groups or living with relatives)

Data from Record of the A-Bomb Disaster published by the City of Hiroshima (figure for 1945) and the 1946 Shisei-yoran, a guide to the city’s administration (figures for 1946 and later).

(Originally published on March 9, 2015)

Noboricho Elementary School: Coal boxes used as desks, school grounds as potato field

Noboricho Park is surrounded on all four sides by tall buildings. Kengo Kurata, 76, said the photo of the “open-air classroom,” in which he appears, was taken on the east side of the park. “I don’t think young people today would believe it,” said Mr. Kurata, and his four former classmates nodded.

The photo shows some 20 second-graders of Noboricho National School attending class in the schoolyard. No textbooks or notebooks can be seen, let alone a blackboard. The photo was taken in the spring of 1946 by an Australian war correspondent who came to Hiroshima with the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces.

Mr. Kurata and his relatives happened to be away from Hiroshima on August 6. He was the youngest of eight siblings. His parents ran a hardware store in Hashimoto-cho in downtown Hiroshima. His eldest brother Shinjiro, then 26 and a fire fighter, and his sister Haruyo, then 13 and a second-year student at Shintoku Girls’ High School, were killed in the atomic bombing. The surviving family members temporarily lived with relatives whose house had not burned. The following March they returned to the city and built a shack.

School opened again in October 1945, using some of the rooms at the Hiroshima Central Broadcasting building, which did not burn down, located in Kami-nagarekawa-cho (now Nobori-cho, Naka Ward), and later rooms at the Hiroshima Central Telephone Exchange in Fukuromachi. But classes eventually had to resume at the school itself because of restoration work on those other buildings. The schoolyard was still filled with debris.

“We used coal or tangerine boxes as desks,” said Mr. Kurata, recalling the time they moved from the telephone office to the school grounds. At the telephone office, at least the students were not exposed to the rain. Takako Suguri, 76, also returned to Hiroshima from the countryside. “Students in the lower grades helped remove the debris, too,” she said. She was born and raised at Shokoji Temple in Nobori-cho, and her grandparents fell victim to the atomic bombing.

By June 1946, a simple building with 10 classrooms had been hastily constructed. With children of returnees from overseas and those who moved in from surrounding areas, there were too many students for the building to accommodate. They were divided into two groups, with one group taking lessons in the morning, the other in the afternoon.

Parents plowed the school grounds and students grew sweet potatoes. Food rations were often delayed or suspended in Hiroshima, and, in the city’s newsletter of June 1946, Mayor Shichiro Kihara asked residents to make use of all available land to grow food. At school, the children were instructed in how to cook wild plants.

School records indicate that the school lunch service resumed in July 1946. Children were given powdered skim milk, which was among the relief items. They also ate dumplings made from dried horseweed and flour, or made from sweet potato powder and seaweed. “They tasted terrible, but we had no choice but to eat them,” said one of the former students, the others agreeing with wry smiles.

In 1947, the School Education Act came into effect, and Noboricho National School was renamed Noboricho Elementary School. But students had to continue studying in the open-air classrooms with ceilings made of reed screens. Lacking resources, the city was unable to construct school buildings as quickly as hoped. Parents formed a committee to raise funds for a new school building. Finally, in 1949, a two-story school building was completed at the location where the school now stands. The building, with its 28 classrooms, cost 11 million yen to construct, half of which was paid by the city government.

Mr. Kurata was a fifth-grader when classes began in the new school building. He remembers taking a one-day school trip to Kosan-ji Temple in Onomichi when he was in sixth grade. The graduation album, with a graduating class of 184 students, included a photo of the school library.

“They joined hands and rebuilt the school amid the ruins of war. They did a remarkable job,” said Mr. Kurata. He went on to study at Noboricho Junior High School and Motomachi High School. After finishing high school, he took over his parents’ hardware shop and got married. When he moved to the Funairi Minami area in the same ward, he still helped the community in which he grew up. He helped build a warehouse for emergency supplies at Noboricho Elementary School, where his two daughters studied.

After they turned 60, Mr. Kurata and his classmates began to get together more often and share memories of how the devastated city was revived.

It was a chilly day at Noboricho Park, but they enjoyed talking about the days when they swam in the Kyobashi River or played baseball on Chuo Street, now a busy road. They hope that younger generations will come to know not only the memories of destruction, but also how people lived through the post-war days, which is less often told.

Honkawa Elementary School: Windows were covered with straw mats, no help in keeping out the chill

Honkawa National School was located closest to the hypocenter, about 410 meters away. According to the Record of the A-bomb Disaster, issued by the City of Hiroshima, 218 students at the school were killed instantly on August 6, 1945. Still, the overall picture of the casualties here is unclear. The school building was constructed in 1928 as the first three-story concrete school building in Hiroshima. Despite the bombing, its framework remained and the school resumed classes in February 1946.

Kojiro Taida, 77, remembers how the walls and floors of the school building were burned and the windows had no window panes. “The wind and rain came through the windows,” he said. After returning from the countryside, where he had stayed during the war, he entered Honkawa Elementary School because Kodo National School in Nekoya-cho (now part of Naka Ward), which he used to attend, had been seriously damaged and was closed.

His father Tokusaburo, then 55, and brother Akinori, then 15, were killed by the blast at their home in Nekoya-cho. Tokusaburo ran a confectionery shop, and Akinori was a third-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School. With six children, including Kojiro, to raise, his mother Takiko, then 35, took a relative’s advice and decided to continue running her husband’s shop.

The window frames of the school building were warped by the A-bomb blast. In winter, straw mats were hung over the windows but did not keep out the chill. The roof was often leaky. A photo taken on the day of the athletic meet in autumn, two years after the bombing, shows windows still lacking window panes.

Honkawa Elementary School was close to the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the A-bomb Dome), which was heavily damaged. Many people visited the school to conduct inspections, including people from the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, or intellectuals from Tokyo. Students often received pencils and other stationery from these visitors, but they were nevertheless always short of supplies.

Many of his classmates lost their parents. Mr. Taida remembers playing a simple version of baseball--played without a second base--and swimming in the Honkawa River, which runs near the school.

When the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, the city’s professional baseball team, was established in January 1950, he went to see the ceremony held at the former West Military Drill Ground site. The baseball team was formed with the aim of lifting the spirits of the Hiroshima people. When the team had a game at Hiroshima Sogo Ground Baseball Park (now part of Nishi Ward), Mr. Taida, then a sixth-grader, voluntarily delivered candy which was sold at a booth and collected the money for it. “Baseball was my only pleasure, and I got to see the game for free if I helped,” he said with a smile.

After finishing junior high school, he worked at his mother’s shop in the daytime and studied in the evening course at Motomachi High School. He then lent financial support to his younger brother and two sisters so they could pursue their university studies. He married in 1965, when Hiroshima was enjoying rapid economic growth. Thirteen family members, including two sons and four grandchildren, have attended Honkawa Elementary School.

Responding to our request, Mr. Taida, his son Masaaki, 46, grandson Shintaro, 10, a fourth-grader, and Yosei, 8, a second-grader, visited the school. Part of the school building was preserved and turned into Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum in 1988. The museum provides a place to learn about peace for the students attending the school, as well as some 20,000 students on school trips and others who visit the museum annually.

Masaaki said, “Even though we studied in the A-bombed building, the memories of the atomic bombing didn’t feel so fresh. I hope the students here will feel the history that’s close to them.” When they enter the fifth grade, students of Honkawa Elementary School begin explaining the museum’s exhibits to children in lower grades and parents.

Mr. Taida said he never had a special occasion to tell his story of the atomic bombing to his children or grandchildren. In calm tones, he then started talking to his grandchildren, who are around the same age as Mr. Taida was when he experienced the bombing. “You’re very fortunate that your father is with you,” he said, “But Grandpa was…”

Kojinmachi Elementary School: Students excited by hustle and bustle of black market Kojinmachi Elementary School, located 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, was completely destroyed. Classes were held in open-air classrooms until September 1948. Fumiaki Kajiya, 75, was in first grade at the time of the bombing. “When the weather was nice, it was much more pleasant than in the dark rooms in the poorly constructed building. I don’t remember anything bad about it,” he said.

When the atomic bomb exploded, Mr. Kajiya was at a nearby house in Osuga-cho (Minami Ward) that was being used as a temporary classroom in case of air raids. He was able to escape on his own, but his sister Fumiko, then 9, was trapped under a column and died instantly, which he learned later. Until the month before the bombing, they had stayed with relatives in Oasa, located in the northern part of the prefecture.

“My mother was at home and she was injured. She kept regretting that we had come back from the countryside. But I was just a child and was quick to bounce back. I was happy when I went back to school in autumn,” said Mr. Kajiya.

“There were no desks available and each student carried a wooden box to and from school. But I was excited to see the hustle and bustle of the black market around Hiroshima Station. We imitated the sales pitches of vendors, watched people bet and play Japanese chess, and sometimes earned a little cash by selling copper wire or brass we collected in the ruins. I was hungry, but felt a new era being ushered in.”

His two elder brothers came home after they were demobilized. They made their younger brother the priority and paid for his education. Mr. Kajiya graduated from Hiroshima University in 1962 and taught at elementary schools in Hiroshima until 1999. He often recalls his experiences as a boy. “Both teachers and students lived their lives to the fullest, and had strong bonds,” he said. The open-air classrooms on the charred ground were what he always remembered in getting back to the basics as an educator.

Damage to national schools in Hiroshima

Name of national school (present address, renamed) Level of damage

Naka Ward

Honkawa (Honkawa-cho) destroyed/burned

Fukuromachi (Fukuro-machi) destroyed/burned

Noboricho (Nobori-cho) destroyed/burned

Nakajima (Kako-machi) destroyed/burned

Otemachi (Ote-machi, closed) destroyed/burned

Hirose (Hirose-cho) destroyed/burned

Kanzaki (Funairi Naka-machi) destroyed/burned

Takeya (Tsurumi-cho) destroyed/burned

Hakushima (Nishi Hakushima-cho) destroyed/burned

Senda (Higashi Senda-machi) destroyed/burned

Seibi affiliated with Army’s Kaikosha

(Hatchobori, closed) destroyed/burned

Kodo (Nekoya-cho, closed) destroyed/burned

Funairi (Funairi Minami) usable

Eba (Eba Minami) usable

Minami Ward

Danbara (Matoba-cho) destroyed/burned

Kojinmachi (Nishi Kaniya) destroyed

Middle school attached to Hiroshima Higher Normal School (Midori-machi, Hiroshima University Attached Elementary School) destroyed/burned

Minami (Minami-machi) partially destroyed

Hijiyama (Kami Shinonome-cho) partially destroyed

Oko (Asahi) partially destroyed

First, Advanced Course (Kasumi, Danbara Junior High School) partially destroyed

Third, Advanced Course (Midori, Midorimachi Junior High School) partially destroyed

Junior High School affiliated with Hiroshima Normal School (Boys) (Shinonome, Hiroshima University Attached Shinonobe Elementary School)

partially destroyed

Ujina (Ujina Miyuki) usable

Ujina branch campus (Motoujina-machi) usable

Niho (Niho-shinmachi) usable

Kusuna (Kusuna-cho) usable

Aosaki (Aosaki) usable

Ninoshima (Ninoshima-cho) usable

Higashi Ward

Ushita (Ushita Asahi) partially destroyed

Onaga (Yamane-cho) burned

Yaga (Yaga) usable

Nishi Ward

Tenma (Tenma-cho) destroyed/burned

Kanon (Minamikanon, Minamikanon Elementary School) destroyed/burned

Misasa (Misasa-machi) destroyed/burned

Oshiba (Oshiba) partially destroyed

Second, Advanced (Minamikanon, Minamikanon Junior High School)

partially destroyed

Fourth, Advanced (Nakahiro-machi) burned

Koi (Koiue) usable

Furuta (Furuenishi-machi) usable

Kusatsu (Kusatsu Higashi) usable

Data from Record of the A-Bomb Disaster published by the City of Hiroshima and the 1946 Shisei-yoran, a guide to the city’s administration.

*It is unknown whether Fourth National School had students.

Fluctuations in number of students

May 1, 1945 41,638

1946 19,201

1947 23,580

1948 26,710

1949 30,431

1950 33,951

(25,836 evacuated to countryside in groups or living with relatives)

Data from Record of the A-Bomb Disaster published by the City of Hiroshima (figure for 1945) and the 1946 Shisei-yoran, a guide to the city’s administration (figures for 1946 and later).

(Originally published on March 9, 2015)