Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Mobilized students feel guilt over surviving

Jun. 19, 2015

During World War II, boys and girls in Japan were ordered to work for the war effort. Children became “mobilized students,” serving the Japanese government. As a consequence of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, there were far more causalities among the mobilized students here than in other prefectures. The youngest of the surviving mobilized students are now in their mid-80s. They are among the shrinking number of people able to relate direct experiences of that terrible war and the reality of the atomic bombing. However, many of them are reluctant to share their accounts because of a sense of guilt over the fact that they survived while others died. This article explores hidden records on the mobilized students of the past and the significance of that fateful day on the present.

The 12-meter-tall Memorial Tower to the Mobilized Students stands to the south of the A-bomb Dome. The inscription on this five-story tower tells how students sacrificed their springtime of life and studies to work for the nation’s war effort. The tower was erected in 1967 by the Hiroshima Prefecture Mobilized Student Victims Association. Members of the group still clean around the tower and offer flowers every month.

Though his legs have grown weak, Michiya Doi, 82, never misses the monthly cleaning time. “I can’t help but feel that today’s peace has been built on the ultimate sacrifices of our friends,” he said. Mr. Doi was a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial High School) when he experienced the atomic bombing. The A-bomb killed a total of 133 students from the school.

Under the government’s guidelines for mobilizing students, which were issued by the education ministry in March 1944 in line with the Outline of Emergency Measures for the Decisive Battle, boys and girls of ages equivalent to students attending today’s junior high school through university were assigned to labor at munitions factories and farms or perform other emergency functions. With the war situation deteriorating, most of the working-age males had been called up for military service, resulting in labor shortages.

In Hiroshima, students were made to work year round starting in June 1944. The prefectural government notified schools that male students should work for 10 hours in principle but no longer than 12 hours, while female students should work no longer than 10 hours.

Upon entering high school, Mr. Doi began working every day as a member of the Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School Service Corps, helping load and unload lumber at the premises of an engineering brigade in today’s Higashi Ward or helping with farm work outside the city. While he and other students were helping to build what seemed like a munitions storehouse in the mountains, one classmate was killed in a cave-in accident. Nevertheless, he believed firmly in sacrificing himself for the sake of the nation, an idea that had been drilled into his head.

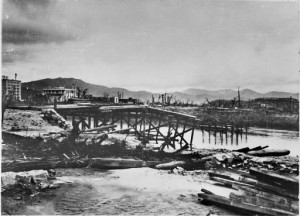

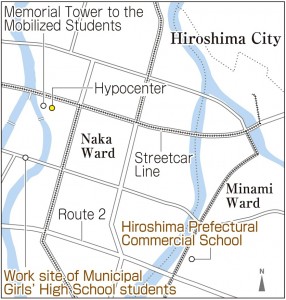

On August 6, 1945, the sixth phase of work to create fire lanes cutting across the Hiroshima delta was under way. To prepare for U.S. air raids, a 198,000 square-meter fire protection zone extending from the Tsurumi-cho area to the Koami area (both in Naka Ward) was being created. Many students were mobilized to help complete this project.

First-year students of the commercial school gathered on the school grounds in Minami-machi (now Minami Ward) before moving to their work site in Zakoba-cho (now Naka Ward) near city hall. They were going to join in efforts to tear down homes. Before he knew what was happening, the atomic bomb exploded and Mr. Doi’s back was burned.

Under the provisions of the 1952 Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors, mobilized students were classified as “paramilitary.” Parents who lost loved ones in the atomic bombing formed a group in 1957 and called for pension payments as high as those given to military and civilian military personnel and demanded that their children be enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine. The prefectural government worked with the group to make a list of victims, who were enshrined at Yasukuni in 1963.

“My mother used to say, ‘I’m still alive thanks to Isao,’ and continued cleaning the tower until the month before she died,” said Kimio Inoue, 79, the chief director of the group. Isao was 13 and a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Junior High School (now Motomachi High School) when he died while helping to dismantle homes in the Koami area. Mr. Inoue’s mother Yoshie died at the age of 90 in 1999. Following in her footsteps, Mr. Inoue became head of the group in 2008.

Membership in the group exceeded 5,000 until the 1970s, but is now below 1,000. Members are siblings of the victims and former mobilized students. One of the priorities for the parents’ generation was to have the victims enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine, but now the group is focused on passing on their memories to the next generation. Testimony of the Lamentation, a collection of writings by 83 mobilized students and victims’ relatives, was published in 2007. The book was added to the group’s website in 2013 and an English translation was made of some of the contents, which is also on its website.

Taeko Teramae, 84, the deputy director of the association, was one of the founders of the group. She was exposed to the bomb while at the Hiroshima Central Telephone Office, 550 meters from the hypocenter, which made her visually impaired in her left eye. Back then, she was a third-year student at Shintoku Girls’ High School. She has been working as an instructor to train “memory keepers” of the A-bomb experiences, a project launched by the Hiroshima city government. Some of the trainees have joined in the task of cleaning around the tower.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings. Lawmakers are now deliberating over bills concerning national security, which could change the nation’s policies in significant ways.

Mr. Doi expressed misgivings. “These days I hear a lot about foreign threats and self-defense. The atmosphere now is similar to what it was like in those days.” Ms. Teramae said, “We believed in dedicating ourselves to our nation. But our friends were robbed of their future. I think those who died would say that war should not be waged again.”

The association and the City of Hiroshima jointly carried out a survey in 1959, and found that 9,111 students were mobilized to help tear down buildings to create fire lanes and 14,143 students were made to work at factories. Combined with other surveys, it has been learned that 7,196 mobilized students were killed in the atomic bombing.

The A-bomb Monument of the Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School stands to the south of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on the west bank of Motoyasu River. The relief on the monument depicts a girl in a sailor-collar school uniform and baggy work pants, flanked by two friends, one holding a wreath and the other a dove. The formula for nuclear energy, E=MC2, also appears on the monument.

Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School) suffered the largest number of casualties. Inscribed on the plaque are the names of 666 students and 10 teachers, 541 of whom were first- and second-year students that were mobilized to help dismantle homes around the area where the monument now stands.

Toshiko Takagi (nee Yoshizumi), 83, recalled, “I also carried roof tiles and lumber from demolished buildings around here. We said ‘See you tomorrow’ and parted.” She was in the sixth class of first-year students.

On the morning of August 6, students were at their work site around 500 meters from the hypocenter. The school record from that time, which still exists, describes the horrific conditions on the day of the bombing.

“Many students lost their eyesight and fell unconscious on the scene. Many moved to Shinbashi Bridge (now Peace Bridge) and Shin-Ohashi Bridge (now West Peace Bridge) for water and jumped into the river. Not a few went into water tanks (used for fighting fires). A small number of students were taken to Ninoshima Island, but only three or four were still alive.”

None of the students survived.

In the July 22, 2000 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun was an article in the series "Record of Hiroshima: Photographs of the Dead Speak." The article explored what happened to 277 first-year students from the school. With the aid of relatives of the victims, information was gleaned on 234 students. But for 184, or 76 percent of these students, not a bone was found.

The municipal high school located in Funairi Kawaguchi-cho (now part of Naka Ward) was partially destroyed. The school building was restored by teachers and students, and lessons resumed on September 18, 1945.

The September 20 entry of the school record states that only one student among those 277 first-year students was present that day: Year 1, Class 6, Yoshizumi. As of October 10, 1945, only 26 first-year students were known to be still alive.

Ms. Takagi believes she survived only by chance. At the time, she temporarily moved from her home in Sakan-cho (now Naka Ward) to Yasu Village (now, Asaminami Ward) for fear of air raids. On the morning of August 6, her bicycle had a flat tire. She thought of walking to school, but her mother told her to stay home as she was worried about her daughter’s health.

On August 8, Ms. Takagi and her father went to where their home had stood, near the hypocenter. They buried her aunt, who was taking care of the house for them. In the ruins, she thought to herself, “Does this mean I must go on living?” But she felt too ashamed to face the thought of her classmates who perished.

When a memorial service was held at Saifukuin Temple near their work site, one parent of a victim said to her, “My child died, but you…” After that, for almost 40 years, she avoided the annual ceremony held in front of the monument on August 6, but would visit the monument on different occasions.

The monument was erected by parents of the victims on the grounds of the school in 1948, when Japan was still under the U.S. occupation. It was moved to its present location in 1957, the 12th anniversary of the students’ deaths. In 1985, the school’s alumni association installed a plaque by the monument.

Fujie Ichiba, 93, was involved in creating the nameplate. “We wanted to leave proof of their lives,” she said. Ms. Ichiba graduated from the school and taught there, and at the time of the A-bombing, had taken students of the advanced course to a canning factory. She identified victims’ names in documents held by Funairi High School before they were inscribed on the plaque.

Ms. Ichiba plans to continue attending the memorial ceremony as long as she lives. Ms. Takagi now offers a prayer to the monument on August 6. They feel reassured that present and former students of the school are making arrangements for the annual ceremony and taking charge of the ceremony’s program and brass band music.

Funairi High School began inviting Miyako Yano (nee Ikeda), 84, to school 10 years ago to share her A-bomb account with students. Ms. Yano, who belonged to the sixth class of the second-year students, will again offer her testimony on July 16 this year. The alumni association has been compiling a booklet to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing.

“They make a habit of teaching about it in ordinary situations,” said Ms. Ichiba. “History will fade if people don’t carry it forward. I feel grateful.” While nodding to Ms. Ichiba’s words, Ms. Takagi expressed mixed feelings. Her second son’s wife graduated from Funairi High School. When the atomic bombing became the subject of their conversation, Ms. Takagi “didn’t feel like telling her about it in detail.”

She still hesitates to recount her experience. The deeper she grieves over her friends’ deaths, the guiltier she feels.

(Originally published on June 8, 2015)

Memorial Tower: Students died believing in service to the nation

The 12-meter-tall Memorial Tower to the Mobilized Students stands to the south of the A-bomb Dome. The inscription on this five-story tower tells how students sacrificed their springtime of life and studies to work for the nation’s war effort. The tower was erected in 1967 by the Hiroshima Prefecture Mobilized Student Victims Association. Members of the group still clean around the tower and offer flowers every month.

Though his legs have grown weak, Michiya Doi, 82, never misses the monthly cleaning time. “I can’t help but feel that today’s peace has been built on the ultimate sacrifices of our friends,” he said. Mr. Doi was a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial High School) when he experienced the atomic bombing. The A-bomb killed a total of 133 students from the school.

Under the government’s guidelines for mobilizing students, which were issued by the education ministry in March 1944 in line with the Outline of Emergency Measures for the Decisive Battle, boys and girls of ages equivalent to students attending today’s junior high school through university were assigned to labor at munitions factories and farms or perform other emergency functions. With the war situation deteriorating, most of the working-age males had been called up for military service, resulting in labor shortages.

In Hiroshima, students were made to work year round starting in June 1944. The prefectural government notified schools that male students should work for 10 hours in principle but no longer than 12 hours, while female students should work no longer than 10 hours.

Upon entering high school, Mr. Doi began working every day as a member of the Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School Service Corps, helping load and unload lumber at the premises of an engineering brigade in today’s Higashi Ward or helping with farm work outside the city. While he and other students were helping to build what seemed like a munitions storehouse in the mountains, one classmate was killed in a cave-in accident. Nevertheless, he believed firmly in sacrificing himself for the sake of the nation, an idea that had been drilled into his head.

On August 6, 1945, the sixth phase of work to create fire lanes cutting across the Hiroshima delta was under way. To prepare for U.S. air raids, a 198,000 square-meter fire protection zone extending from the Tsurumi-cho area to the Koami area (both in Naka Ward) was being created. Many students were mobilized to help complete this project.

First-year students of the commercial school gathered on the school grounds in Minami-machi (now Minami Ward) before moving to their work site in Zakoba-cho (now Naka Ward) near city hall. They were going to join in efforts to tear down homes. Before he knew what was happening, the atomic bomb exploded and Mr. Doi’s back was burned.

Under the provisions of the 1952 Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors, mobilized students were classified as “paramilitary.” Parents who lost loved ones in the atomic bombing formed a group in 1957 and called for pension payments as high as those given to military and civilian military personnel and demanded that their children be enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine. The prefectural government worked with the group to make a list of victims, who were enshrined at Yasukuni in 1963.

“My mother used to say, ‘I’m still alive thanks to Isao,’ and continued cleaning the tower until the month before she died,” said Kimio Inoue, 79, the chief director of the group. Isao was 13 and a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Junior High School (now Motomachi High School) when he died while helping to dismantle homes in the Koami area. Mr. Inoue’s mother Yoshie died at the age of 90 in 1999. Following in her footsteps, Mr. Inoue became head of the group in 2008.

Membership in the group exceeded 5,000 until the 1970s, but is now below 1,000. Members are siblings of the victims and former mobilized students. One of the priorities for the parents’ generation was to have the victims enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine, but now the group is focused on passing on their memories to the next generation. Testimony of the Lamentation, a collection of writings by 83 mobilized students and victims’ relatives, was published in 2007. The book was added to the group’s website in 2013 and an English translation was made of some of the contents, which is also on its website.

Taeko Teramae, 84, the deputy director of the association, was one of the founders of the group. She was exposed to the bomb while at the Hiroshima Central Telephone Office, 550 meters from the hypocenter, which made her visually impaired in her left eye. Back then, she was a third-year student at Shintoku Girls’ High School. She has been working as an instructor to train “memory keepers” of the A-bomb experiences, a project launched by the Hiroshima city government. Some of the trainees have joined in the task of cleaning around the tower.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings. Lawmakers are now deliberating over bills concerning national security, which could change the nation’s policies in significant ways.

Mr. Doi expressed misgivings. “These days I hear a lot about foreign threats and self-defense. The atmosphere now is similar to what it was like in those days.” Ms. Teramae said, “We believed in dedicating ourselves to our nation. But our friends were robbed of their future. I think those who died would say that war should not be waged again.”

The association and the City of Hiroshima jointly carried out a survey in 1959, and found that 9,111 students were mobilized to help tear down buildings to create fire lanes and 14,143 students were made to work at factories. Combined with other surveys, it has been learned that 7,196 mobilized students were killed in the atomic bombing.

666 students died, survivor determined to continue attending memorial ceremony

The A-bomb Monument of the Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School stands to the south of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on the west bank of Motoyasu River. The relief on the monument depicts a girl in a sailor-collar school uniform and baggy work pants, flanked by two friends, one holding a wreath and the other a dove. The formula for nuclear energy, E=MC2, also appears on the monument.

Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School) suffered the largest number of casualties. Inscribed on the plaque are the names of 666 students and 10 teachers, 541 of whom were first- and second-year students that were mobilized to help dismantle homes around the area where the monument now stands.

Toshiko Takagi (nee Yoshizumi), 83, recalled, “I also carried roof tiles and lumber from demolished buildings around here. We said ‘See you tomorrow’ and parted.” She was in the sixth class of first-year students.

On the morning of August 6, students were at their work site around 500 meters from the hypocenter. The school record from that time, which still exists, describes the horrific conditions on the day of the bombing.

“Many students lost their eyesight and fell unconscious on the scene. Many moved to Shinbashi Bridge (now Peace Bridge) and Shin-Ohashi Bridge (now West Peace Bridge) for water and jumped into the river. Not a few went into water tanks (used for fighting fires). A small number of students were taken to Ninoshima Island, but only three or four were still alive.”

None of the students survived.

In the July 22, 2000 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun was an article in the series "Record of Hiroshima: Photographs of the Dead Speak." The article explored what happened to 277 first-year students from the school. With the aid of relatives of the victims, information was gleaned on 234 students. But for 184, or 76 percent of these students, not a bone was found.

The municipal high school located in Funairi Kawaguchi-cho (now part of Naka Ward) was partially destroyed. The school building was restored by teachers and students, and lessons resumed on September 18, 1945.

The September 20 entry of the school record states that only one student among those 277 first-year students was present that day: Year 1, Class 6, Yoshizumi. As of October 10, 1945, only 26 first-year students were known to be still alive.

Ms. Takagi believes she survived only by chance. At the time, she temporarily moved from her home in Sakan-cho (now Naka Ward) to Yasu Village (now, Asaminami Ward) for fear of air raids. On the morning of August 6, her bicycle had a flat tire. She thought of walking to school, but her mother told her to stay home as she was worried about her daughter’s health.

On August 8, Ms. Takagi and her father went to where their home had stood, near the hypocenter. They buried her aunt, who was taking care of the house for them. In the ruins, she thought to herself, “Does this mean I must go on living?” But she felt too ashamed to face the thought of her classmates who perished.

When a memorial service was held at Saifukuin Temple near their work site, one parent of a victim said to her, “My child died, but you…” After that, for almost 40 years, she avoided the annual ceremony held in front of the monument on August 6, but would visit the monument on different occasions.

The monument was erected by parents of the victims on the grounds of the school in 1948, when Japan was still under the U.S. occupation. It was moved to its present location in 1957, the 12th anniversary of the students’ deaths. In 1985, the school’s alumni association installed a plaque by the monument.

Fujie Ichiba, 93, was involved in creating the nameplate. “We wanted to leave proof of their lives,” she said. Ms. Ichiba graduated from the school and taught there, and at the time of the A-bombing, had taken students of the advanced course to a canning factory. She identified victims’ names in documents held by Funairi High School before they were inscribed on the plaque.

Ms. Ichiba plans to continue attending the memorial ceremony as long as she lives. Ms. Takagi now offers a prayer to the monument on August 6. They feel reassured that present and former students of the school are making arrangements for the annual ceremony and taking charge of the ceremony’s program and brass band music.

Funairi High School began inviting Miyako Yano (nee Ikeda), 84, to school 10 years ago to share her A-bomb account with students. Ms. Yano, who belonged to the sixth class of the second-year students, will again offer her testimony on July 16 this year. The alumni association has been compiling a booklet to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing.

“They make a habit of teaching about it in ordinary situations,” said Ms. Ichiba. “History will fade if people don’t carry it forward. I feel grateful.” While nodding to Ms. Ichiba’s words, Ms. Takagi expressed mixed feelings. Her second son’s wife graduated from Funairi High School. When the atomic bombing became the subject of their conversation, Ms. Takagi “didn’t feel like telling her about it in detail.”

She still hesitates to recount her experience. The deeper she grieves over her friends’ deaths, the guiltier she feels.

(Originally published on June 8, 2015)